In this new series I’ll be taking a close look at the way the astrological planets and Zodiac signs were depicted in the Islamic world, through a series of objects dating from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (AD). Why this specific period:

“It was only in the twelfth century that individual astrological images […], or astrological cycles that might include either the seven planets, the twelve signs of the Zodiac, or both groups in a concentric arrangement, began to appear on stone reliefs and on metalwork in a geographical area that extended eastward from the Jazira ( a region including modern northern Iraq, northeastern Syria, and southeastern Turkey) to eastern Khurasan (corresponding to present-day eastern Iran and Afghanistan). "1

The figurative style used in many of these objects through the medium of inlaid work is particularly lovely to my eyes and I’ve been focusing on it for other purposes, so there’s also a little subjectivity to the selection, but I have to draw a line at where to stop this non-exhaustive survey anyway. I’ll complement the images with correspondences provided in Ghāyat al-Hakīm, the tenth- or eleventh-century magical text from which I translated ink recipes a year ago.

These images and symbols are largely familiar, but not always, and the ways in which they differ from today’s globally standardised images remind us that we live in a culturally impoverished era.

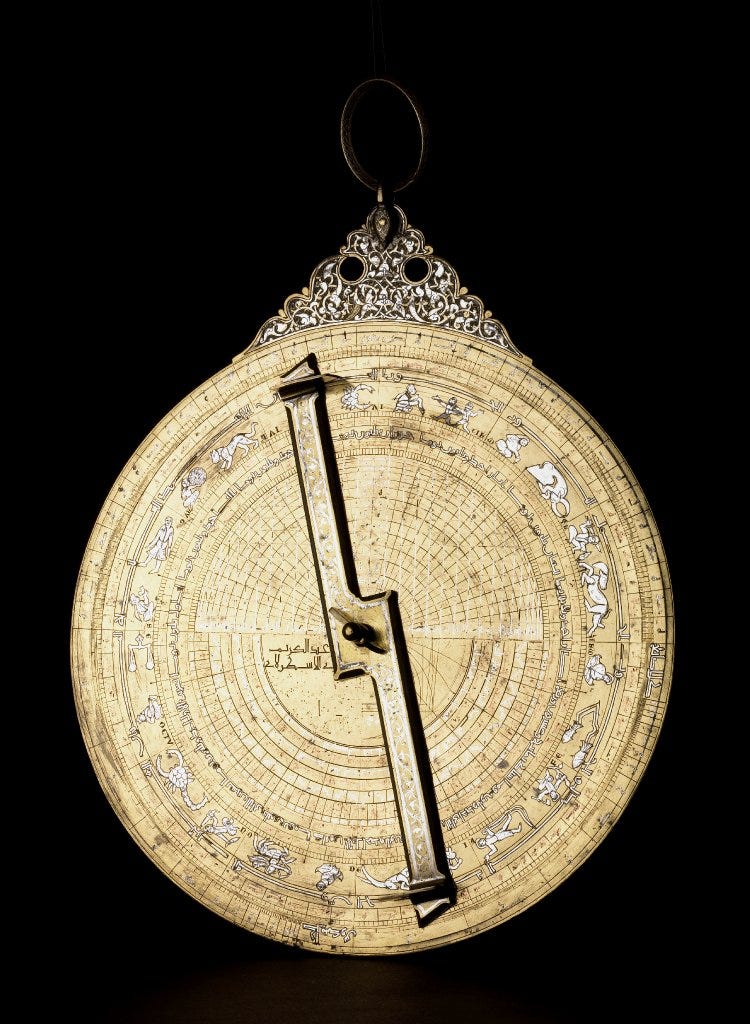

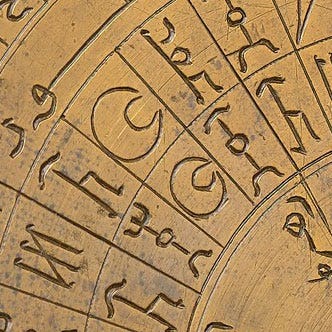

For a brief but erudite general introduction, I suggest Astronomy and Astrology in the Medieval Islamic World by Marika Sardar.2 I’m just going to put it in a nutshell: Astronomers of the Islamic world inherited knowledge from Greek, Iranian and Indian sources, but took the science to new heights of precision, refining instruments and building observatories to deepen their understanding of the movements of celestial bodies. The astrological aspect (the influence of such bodies on human lives) was controversial but for all that it was deeply embedded in the various cultures and a popular subject for decorative and/or talismanic art.3

The medieval geocentric model of the Cosmos, in its general shape, was shared by both the Islamic and Christian worlds: Around the Earth4, the seven “wanderers” (planetai) rotate, each defining its own separate sphere. These are in order (as observable from here): the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. The eighth sphere is that of Fixed Stars, in other words the constellations that appear stationery to our eyes (the entire sphere “rotating” as one), including those that correspond the zodiac and to the lunar mansions5. The model continues into archetypal and divine spheres, but this is as far as we need to go for this series’ purposes.

The Objects

Before moving on to our first planet, the Moon, I need to introduce the principal objects that provided the astrological images in question. (As usual, the first article in a series ends up extra-long!) Other objects will also enter the picture on occasion, but our main cast is as follows:

Picturing the Moon (Al-Qamar القمر)

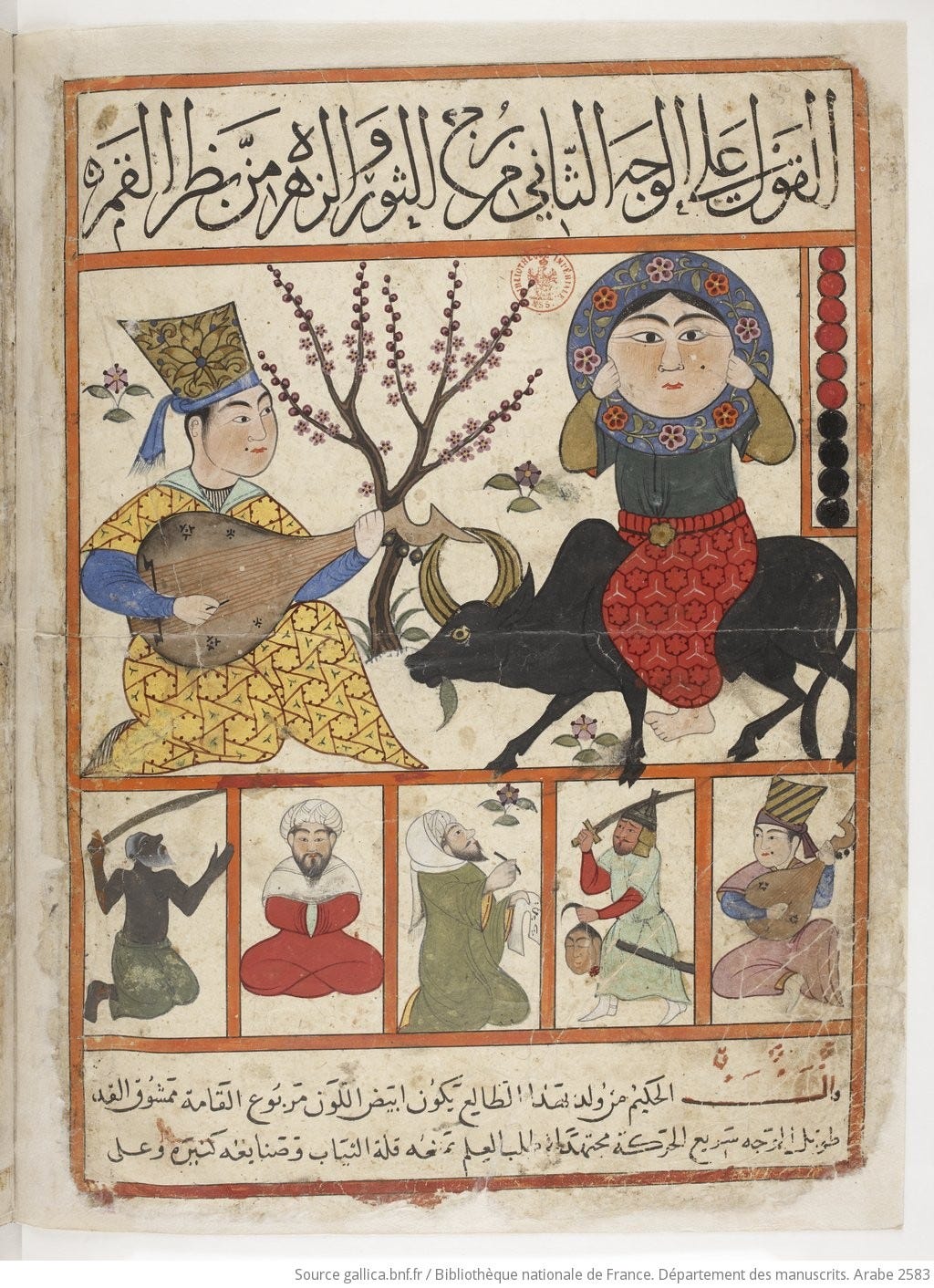

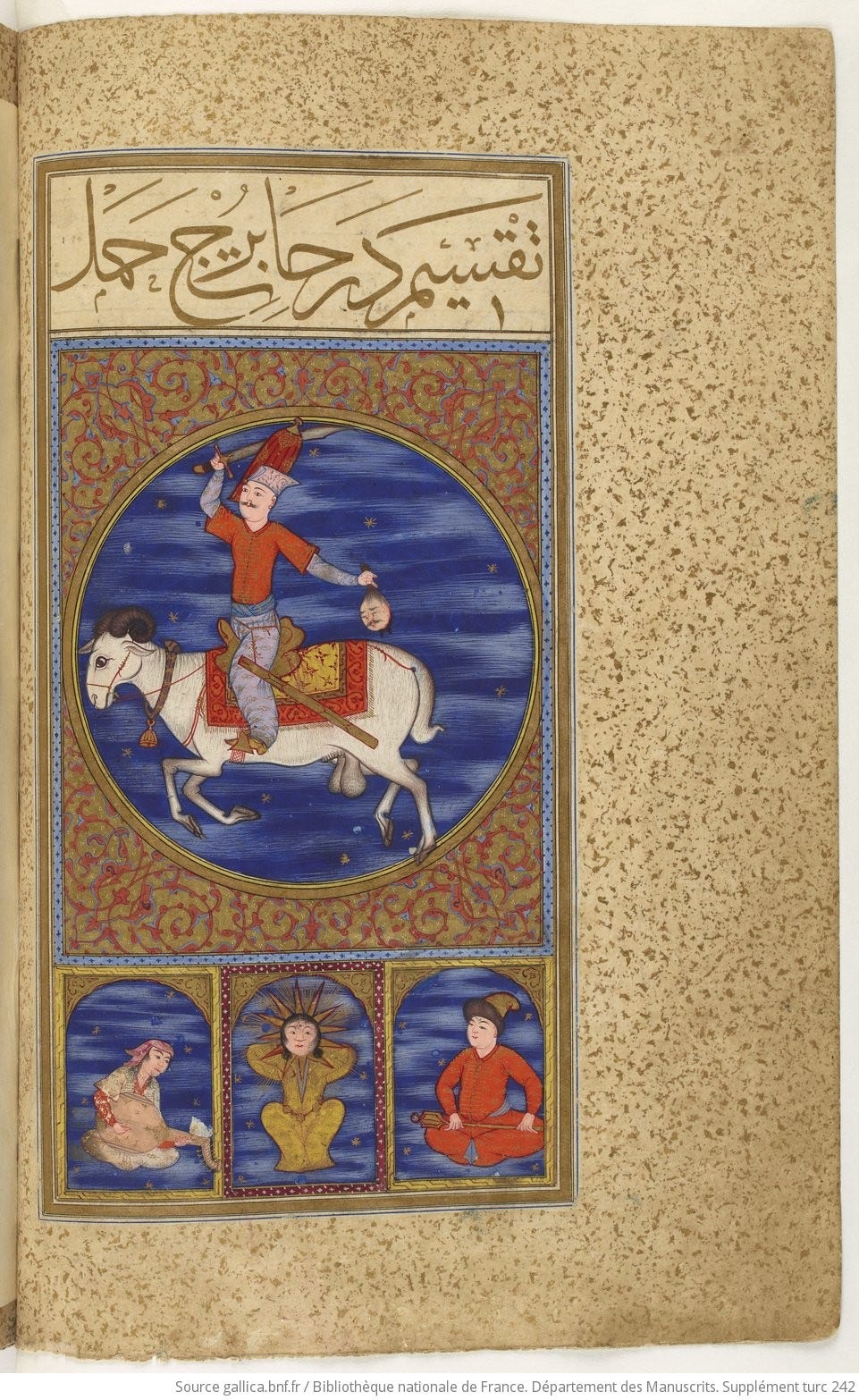

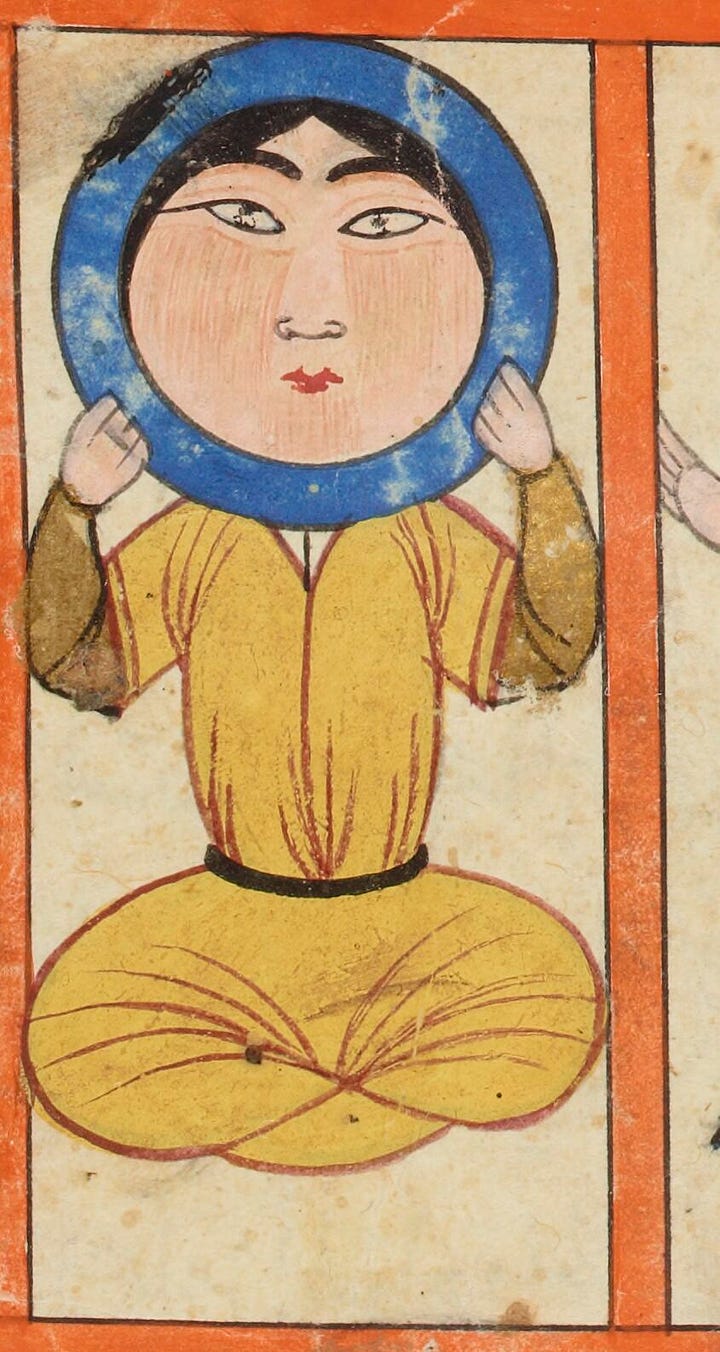

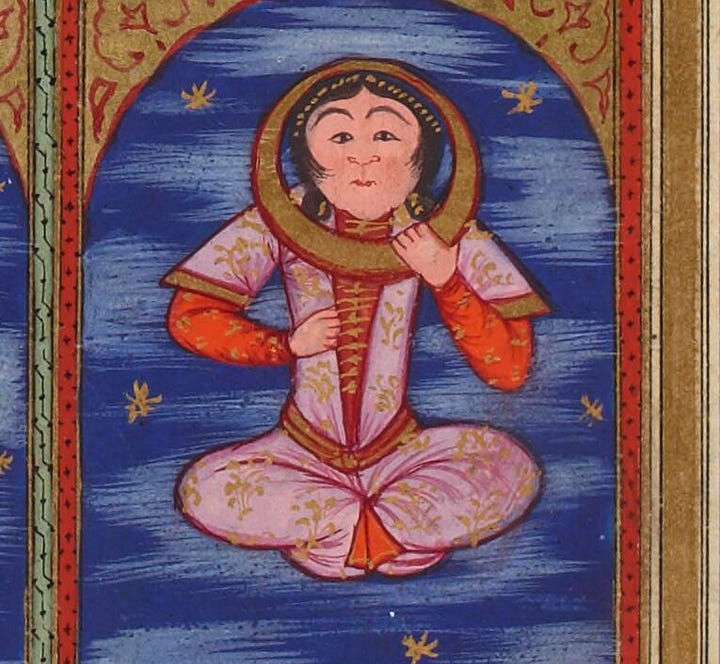

Perhaps mercifully after such a long intro, the Moon is straightforward in its imagery: a human figure holding a crescent (inscribed in a circle) around its face or as a face. This tends to be a female figure, though I’m not convinced by Carboni’s statement that “[t]he concept of the feminine nature of the Moon probably developed in Arabic folklore”6 for the simple reason that in Arabic the moon is a masculine word, as are the words for full moon (badr) and crescent (hilāl). It’s the sun that is feminine. Moon deities in the region were male as far as I know. I could be wrong but I don’t think the feminine imagery of the Moon owes anything to Arab culture, but instead came from the East along with the style of clothing she’s usually portrayed wearing.

Because the Moon has such importance and positivity in Islamic cultures, this figure can sometimes be seen on its own, repeated on certain objects without any other astrological context, evidently as a talismanic and protective presence.

Not all objects depict the planets as firgures on their own, but it’s extremely common for the zodiac images to have the planetary lords built in to the iconography of the sign. This is particularly true of Cancer, which is ruled by the Moon: it almost always shows the planet, reduced to its crescent or disc face, between the crab’s claws.

In terms of symbol, the crescent (going back to Greco-byzantine tradition) comes as no surprise. It can face left or right, and is also the symbol for the metal silver.

To finish, here are some of the correspondences for the Moon listed in Ghāyat al-Hakīm:

Languages: Slavonic الصقالبة and Sabean الصابئة

Clothing: furs الفراء and kerchiefs المناديل

Taste: Insipid تفاهة

Places: Springs العيون, swamps السباخ, snow-covered places مواضع الثلوج, water in general المياه اجمع

Gemstones: Small pearls اللؤلؤ الصغار

Metals: Silver الفضّة and white metals الأجساد البيض

Plants: Papyrus البردي, reeds القصب, daisies الاقحوان, all sweet-smelling white plants, all trees that don’t stand on a “leg”, grasses الحشائش والمراعي, legumes البقول

Pharmaceutics: Those that are both food and medicine such as cinnamon القرفة , long pepper الدار فلفل , ginger الزنجبيل , cassia دار صيني , and any that is cold and moist with an insipid taste and a white or green hue.

Animals: Grey workhorses البراذين الشهب, mules البغال, asses الحمير, cows البقر, rabbits الارانب, birds that are light and fast-moving in the air, every white bird and water bird, white snakes and white worms.

Colours: Made up of yellowness الصفرة and blonde الشقرة hues

Next stop: Mercury!

Carboni, Stefano. Following the Stars: Images of the Zodiac in Islamic Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1997, p6.

I’ve given an idea of the importance of the planets in my series examining the art of Nizāmi’s Haft Peykar.

I have to scream about this here: Medieval people did not believe the Earth was flat. Only us modern primitives who never look at the skies can be so wilfully stupid. Ancient cultures were fiercely observant of natural phenomenons above and below. The earliest writings revealing an understanding of the Earth being spherical date back to fifth century BC Greece, and Eratosthenes calculated the planet’s circumference around 240BC. The entire Medieval world was based on Greek teachings and took it for granted the Earth was a sphere.

Segments of the ecliptic through which the Moon passes in its orbit around the Earth

Following the Stars p11.

Wonderful! Very interesting and, as always, erudite and full of beauty. It’s work like this that may, if anything can, save us from drowning in the vast and polluted ocean of cultural impoverishment that the blindly arrogant, blinkered and bone-headed ‘culture’ of materialism and consumption willingly flails in.

This is stunning, thank you! I am absolutely here for this journey, such amazing treasures. Seeing these astrolabes I wondered what treasured creations humanity would be looking back on 1,000 years from now…