Picking up from my introduction to diapering, I’m still following the thread of these oft-overlooked patterns, now through a work of literature that is a unique source of visual inspiration.

Haft Peykar, “the Seven Beauties” is also known as the Bahrāmnāmeh or “Book of Bahram”. It was composed by Nizāmi in 1197 as part of his Khamsa (Quintet) and tells the story of Shah Bahram and his seven brides. In a very small nutshell1, each day of the week Bahram visits one of the princesses in her domed pavilion and listens to a story from her before they spend the night together. On the face of it a romantic epic, simultaneously erotic and moralising. In this respect alone it has long been considered a masterpiece and captured the imagination of countless artists of the Persianate world. But the poem presents rather obvious hints inviting a deeper level of reading…

Our perception of Seven as a sacred number comes to us from the astronomers of Sumer, who “first singled out the Seven Heavenly Bodies2 [and] attributed divine status to them”3. They accordingly organised time on the basis of the seven-day week, with each day ruled by a planet (and named after its titular deity), and this system was handed down via Judaism then the Church, essentially unchanged to this day. We find it here as the central axis around which the narrative is articulated, the protagonist going through the week and therefore from planet to planet through the visual device of their associated colours. These colours define the dwelling of and are respectively worn by each princess (and by Bahram when uniting with each), but they also happen to make up the stages of a spiritual progression of the soul — a progression actually described in some Sufi teachings as talwīn تلوين, the “colouring”. The poem turns out, then, to be an initiatory tale at the end of which the pious Bahram achieves the highest state of liberation:

“As Shāh Bahrām moves from one Dome to the next in his week of initiation, in spiritual terms he rises through the Seven Heavenly Spheres, of which the Seven Brides are the wardens.”4

His brides are his spiritual teachers, and while they are in a way the spirits of the Spheres, they are at the same time fully embodied sensual women: I highlight this because it’s a healthy reminder that the separation of holy and earthly is artificial and only took root relatively recently. Bahram’s union with each of them is both spiritual integration and great sex. The text and images of Haft Peykar are both deeply significant and a feast for the senses. 5

The images

For this seven-part series, I’ll be looking at images from six Haft Peykar manuscripts that are complete and therefore each have the full set of seven illustrations. Each image is linked to its source page where you can go to zoom in on the fine details.

The manuscripts themselves, from the oldest to the newest, are:

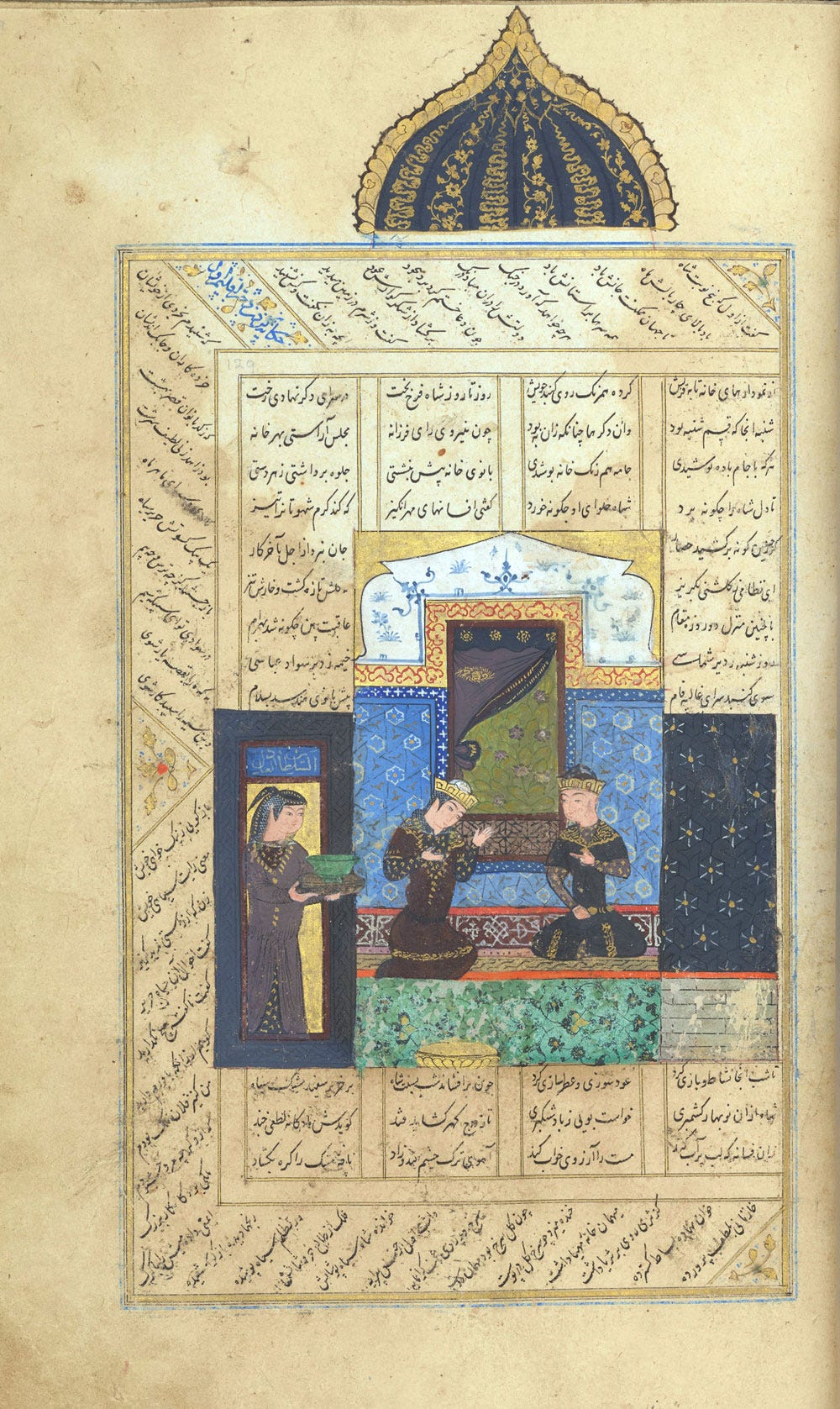

Chester Beatty Library, Per 171 (AD 1492, AH 897), unknown artist.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 13.228.7.8 (AD 1524, AH 931), painted by Shaikh Zada.

Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art, F1908.271 to 277 (AD 1548, AH 955), unknown artist

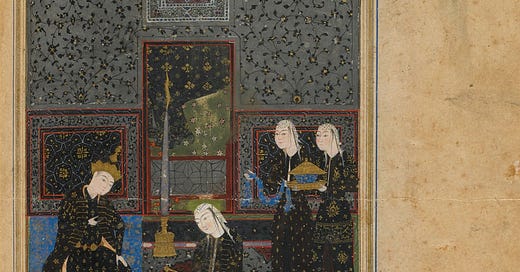

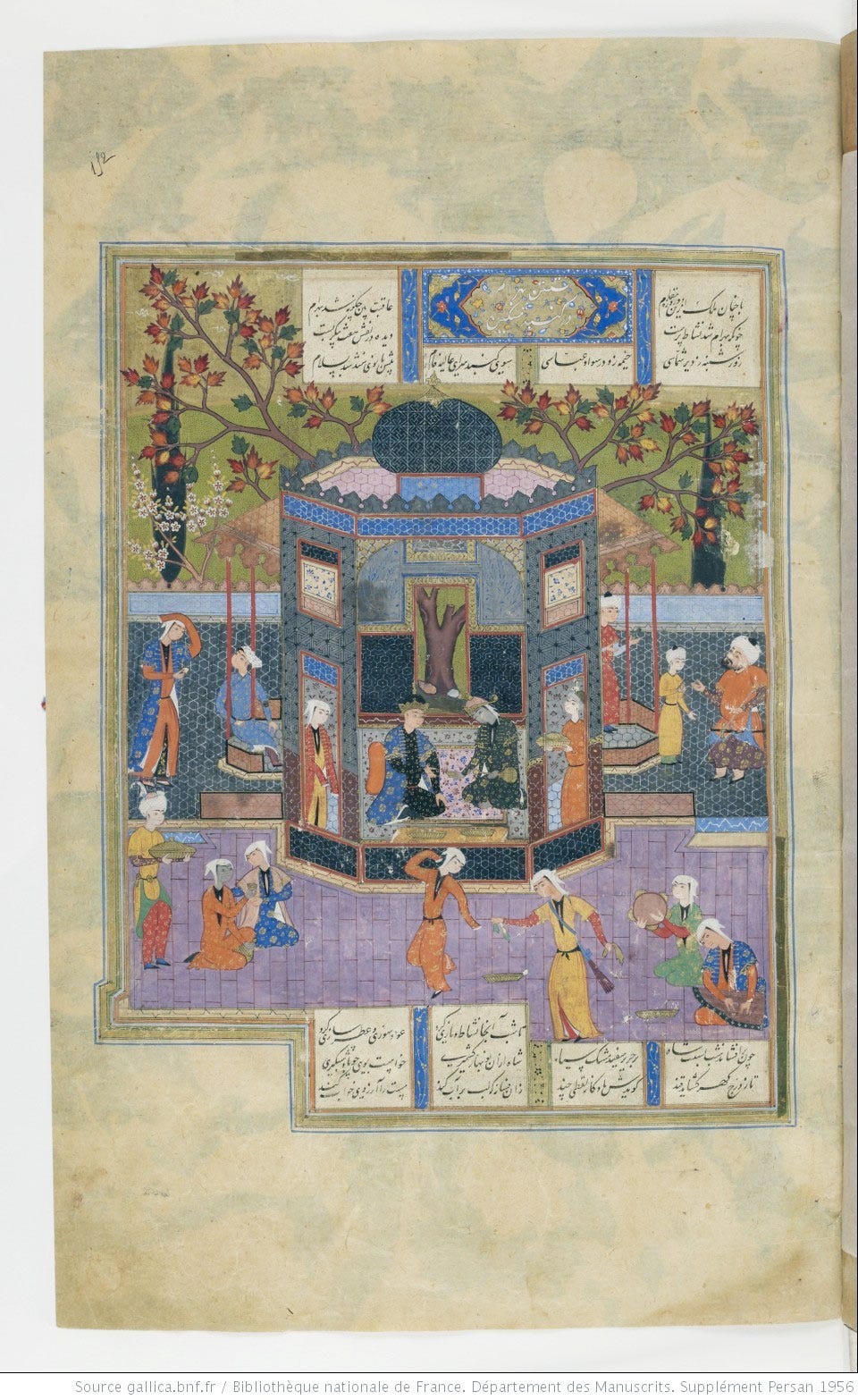

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Départment des Manuscrits, Supplément Persan 1956 (AD 1560, AH 965), unknown artist

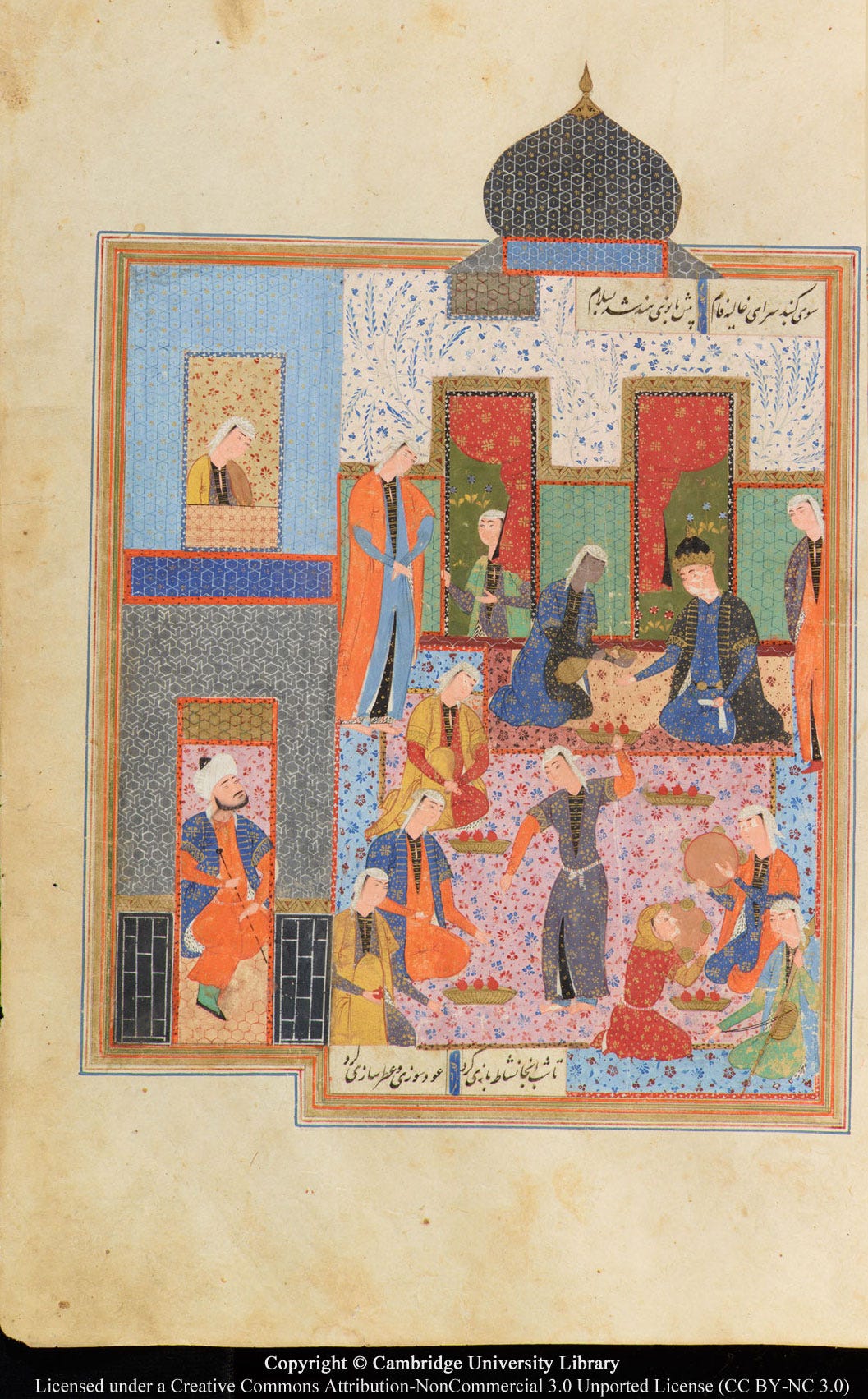

Cambridge University Library, MS Add.3139 (17th c. AD, 11th c. AH), unknown artist.

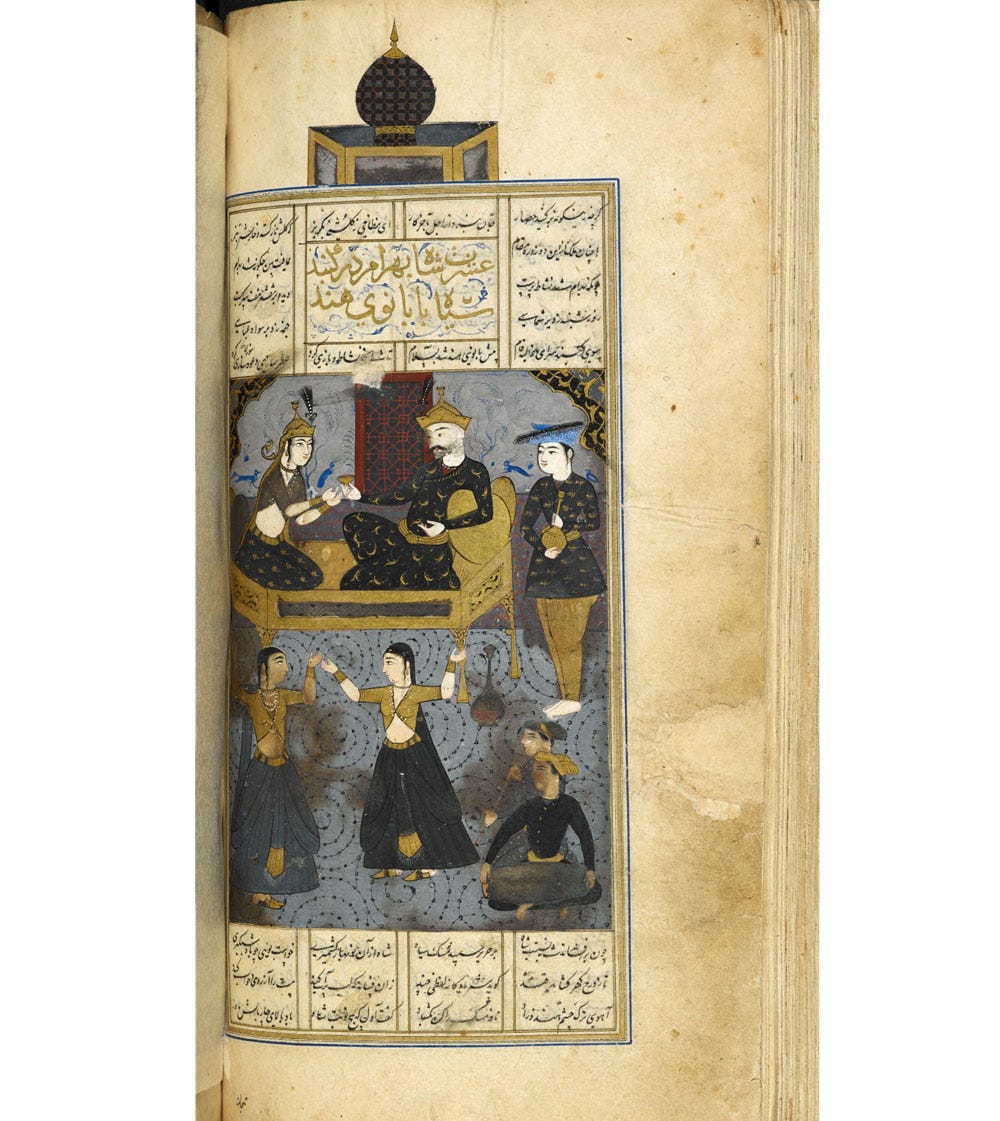

British Library, Add MS 6613, ff138v-196r (AD 1671, AH 1076), painted by Ṭālib Lālā.

And now, after this lengthy prologue, we can dive into the visuals of this first stage of Bahram’s story – and the subject of this series, the diaper patterns hidden in the images!

The Black Dome

On Saturday, Bahram visits Fūrak, Princess of India, clad in Black, under the sign of Saturn, Lord of Lead.

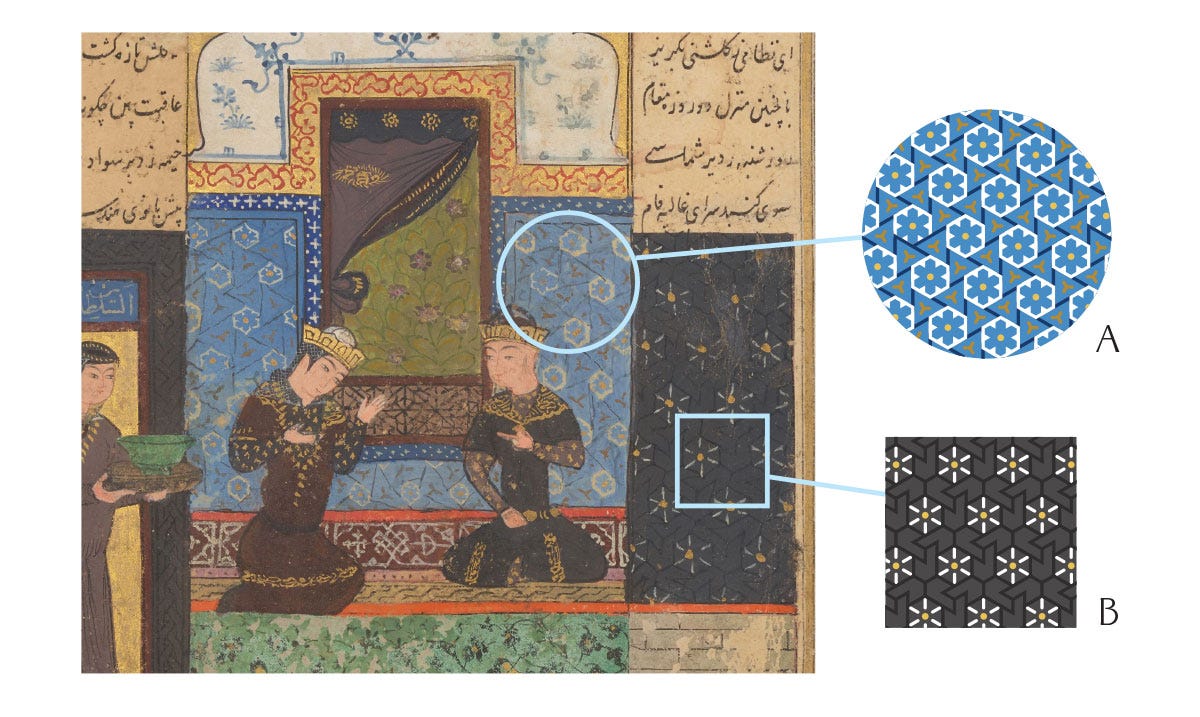

This earliest manuscript also has the simplest illustrations, but already two patterns to interest us:

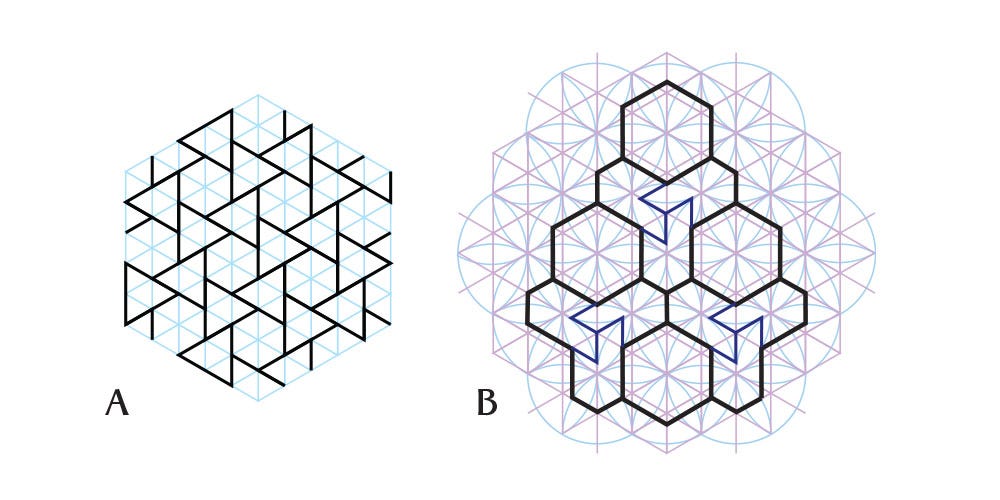

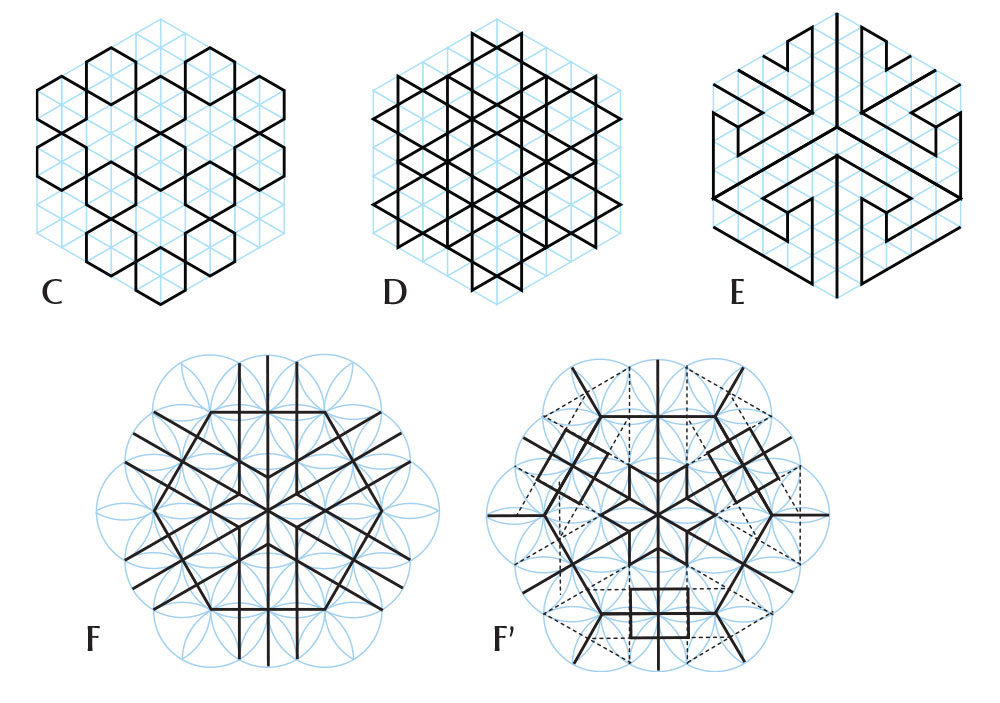

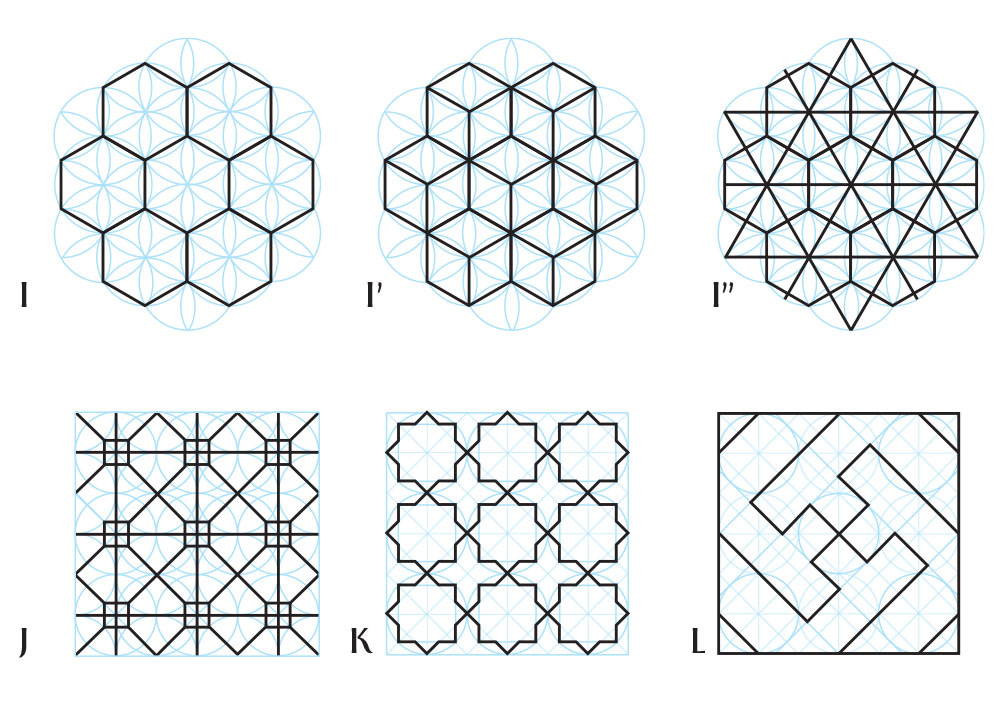

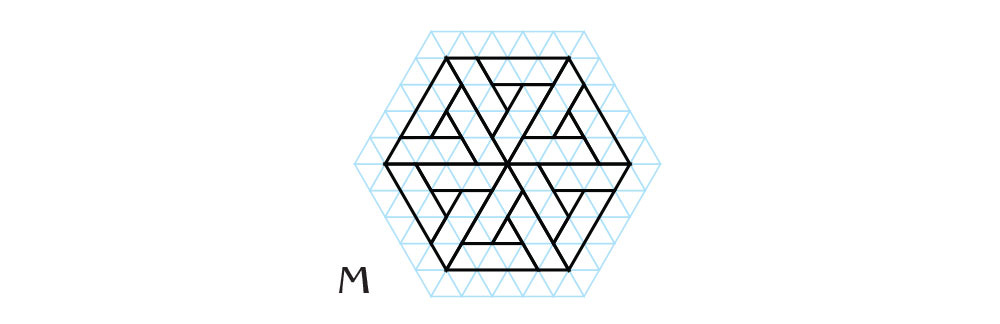

They are both based on a grid of triangles6 and we have already encountered them; B is only different in the extra lines (in dark blue) separating this three-pointed shape into three interlocking ones.

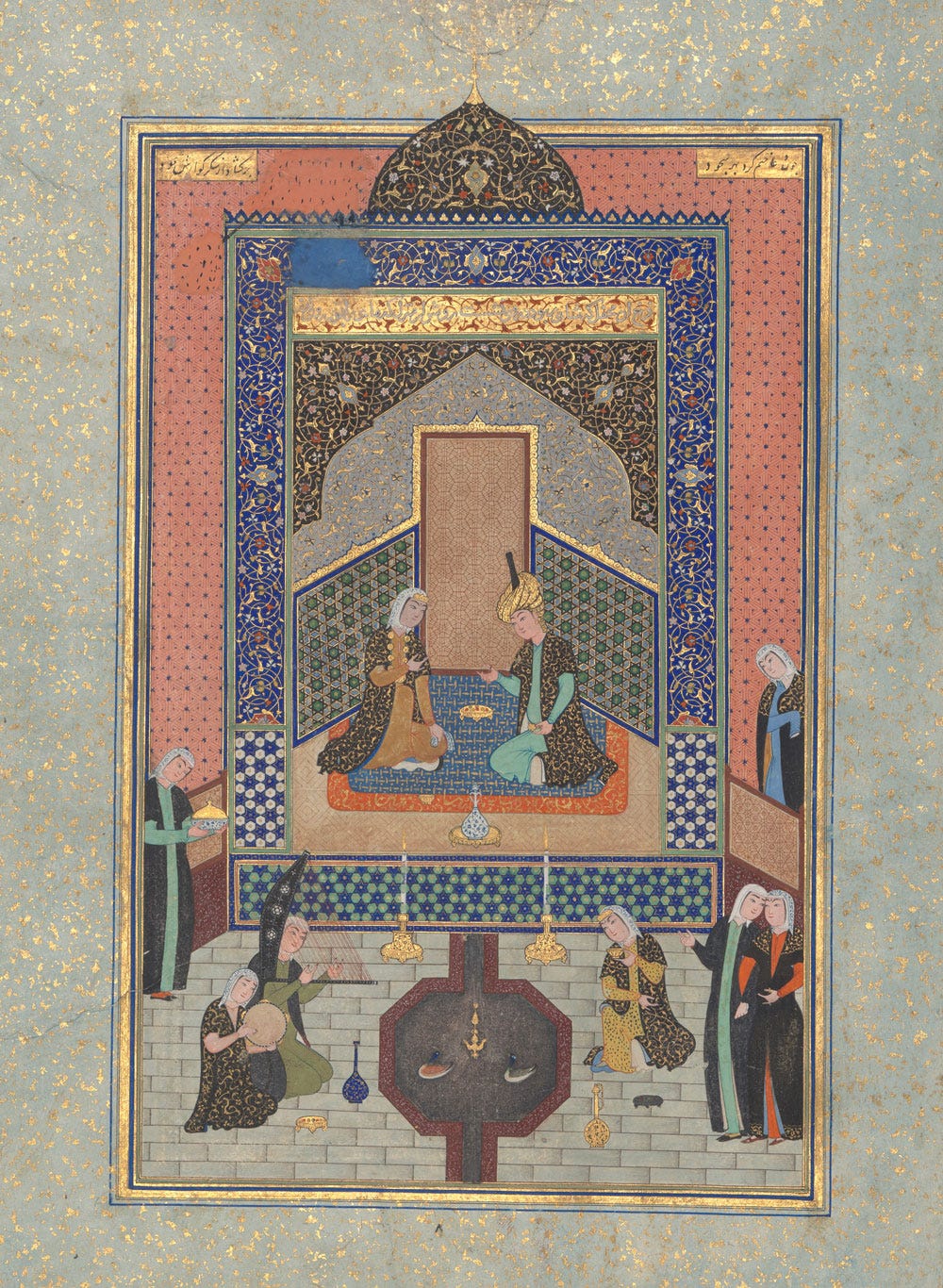

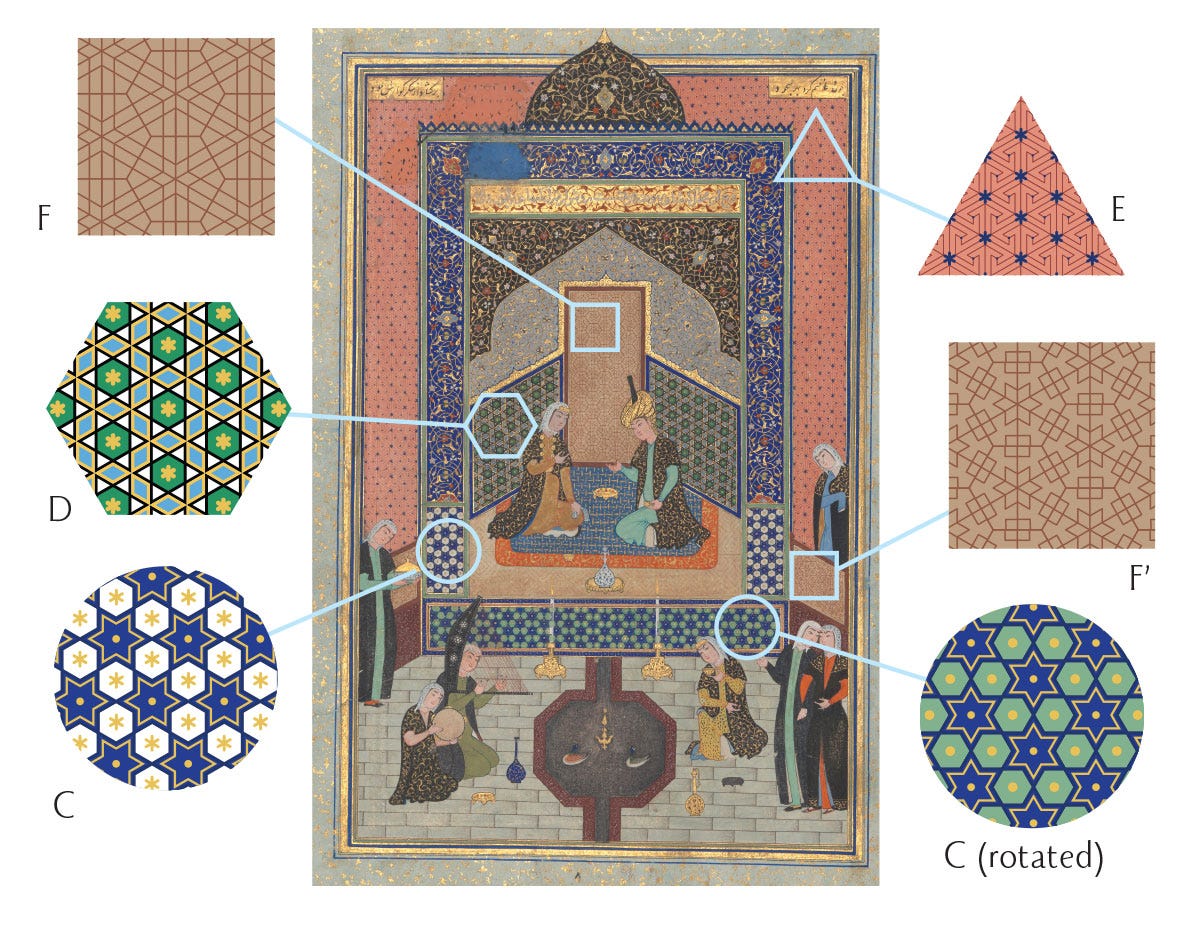

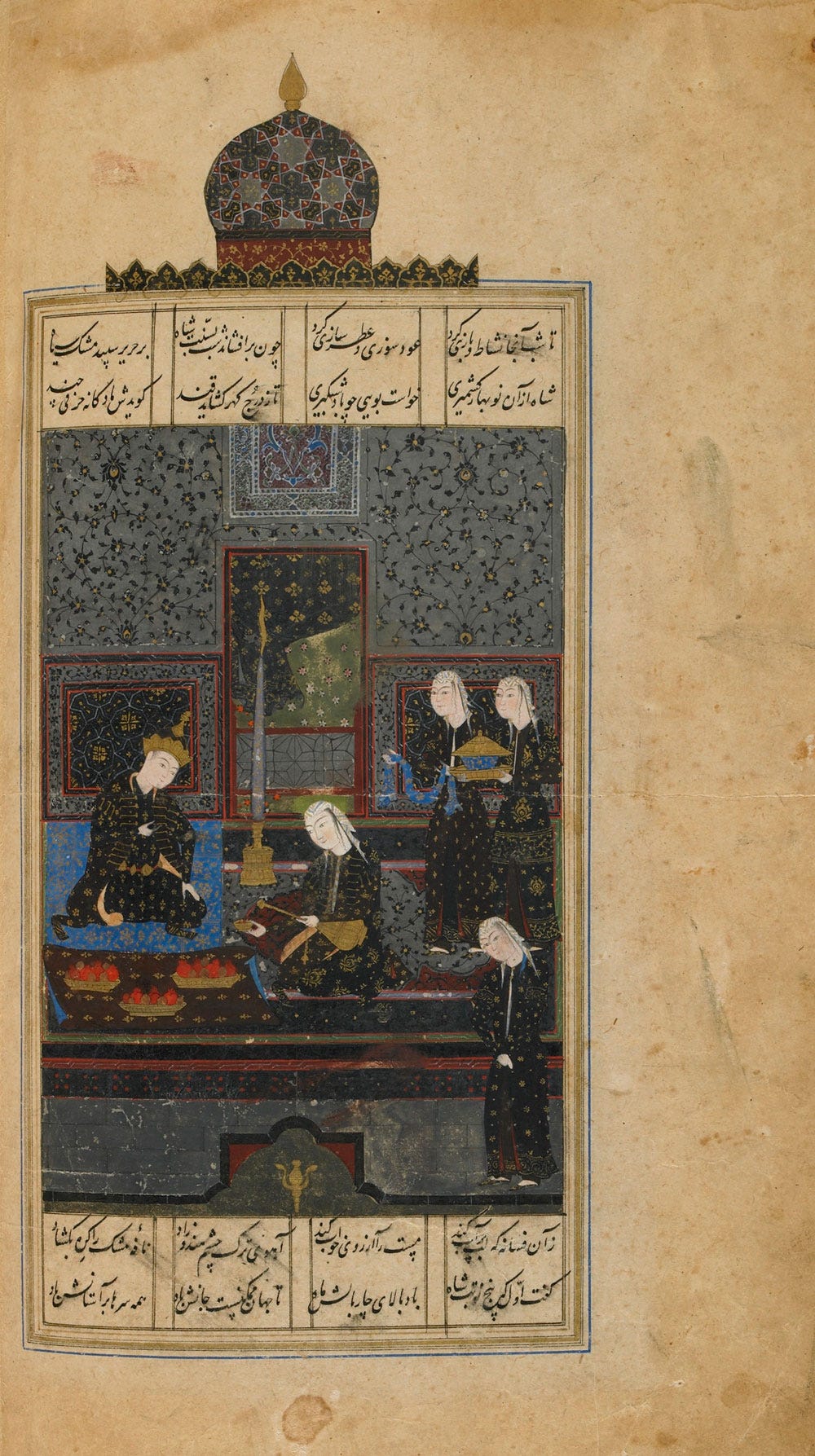

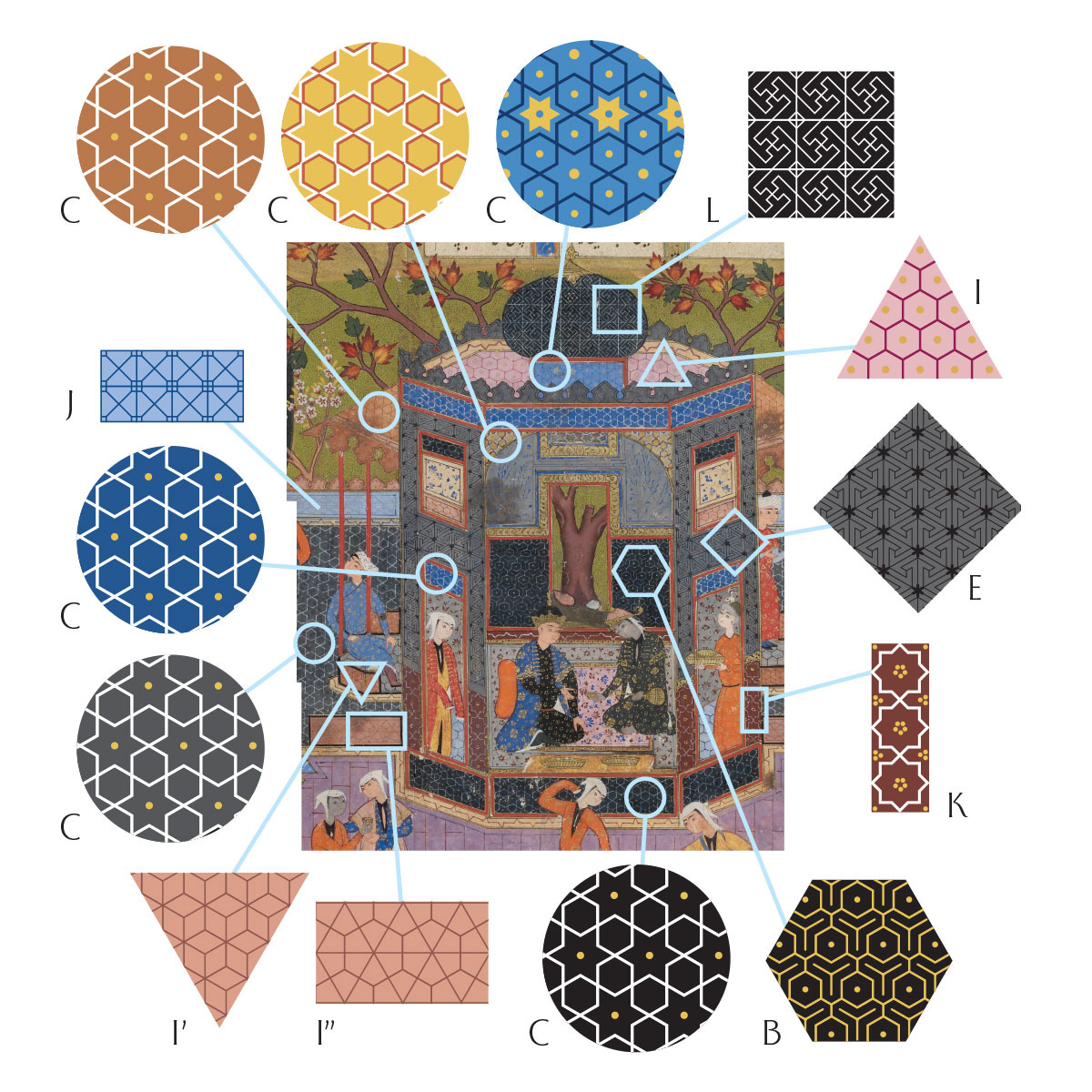

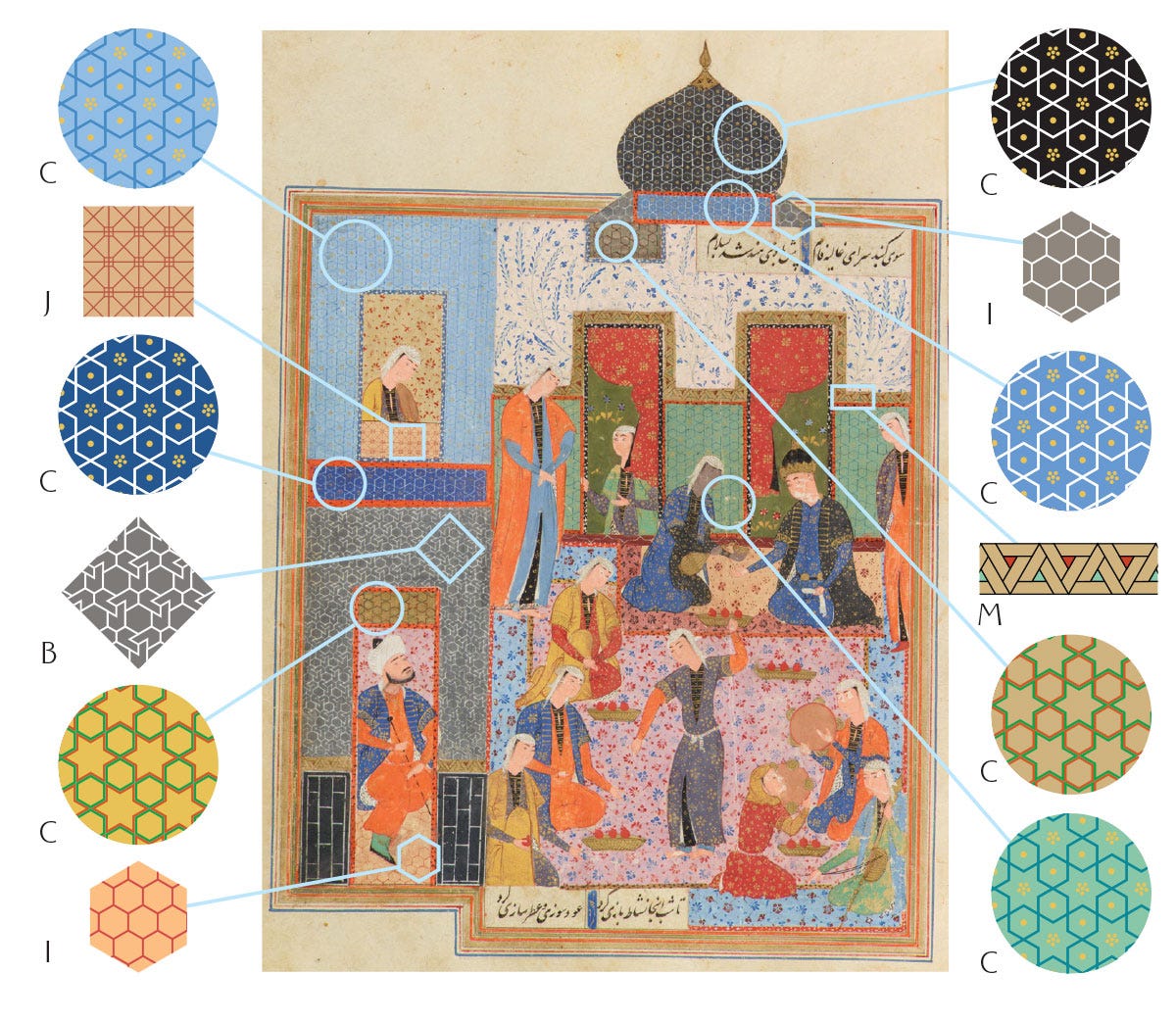

This next folio brings us to the classic iconography for this poem: The dome itself is represented in the appropriate colour, and inside the pavilion Bahram is with the princess, both wearing a caftan of the same colour (sometimes this caftan is the only really clear indication of what dome/colour we’re at) while music, dance and other activities take place. The stylised perspective shows us the outside and inside walls at the same time, and every surface requires a pattern of some kind.

All of these are derived from the grid of triangles. We’re going to continuing to see grid C so often it’s clearly a go-to pattern. I must say that because the scenes are architectural, it’s hard to be sure, for some of these, if they’re truly diapers (patterns added to embellish a flat area of colour, that wouldn’t exist in real life) or representations of real-life patterned doors, panels and walls (e.g. F and F’). I’m not putting too fine a point on it, though, and simply reproduced all the geometric patterns I could find.

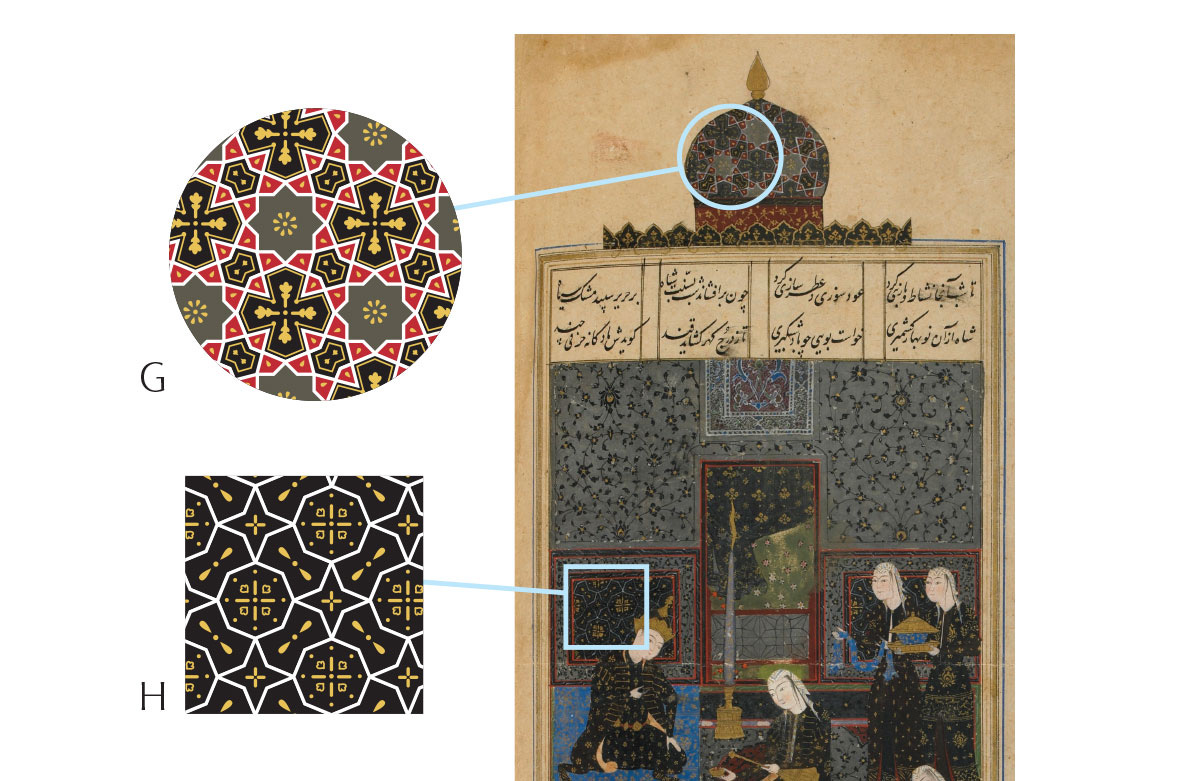

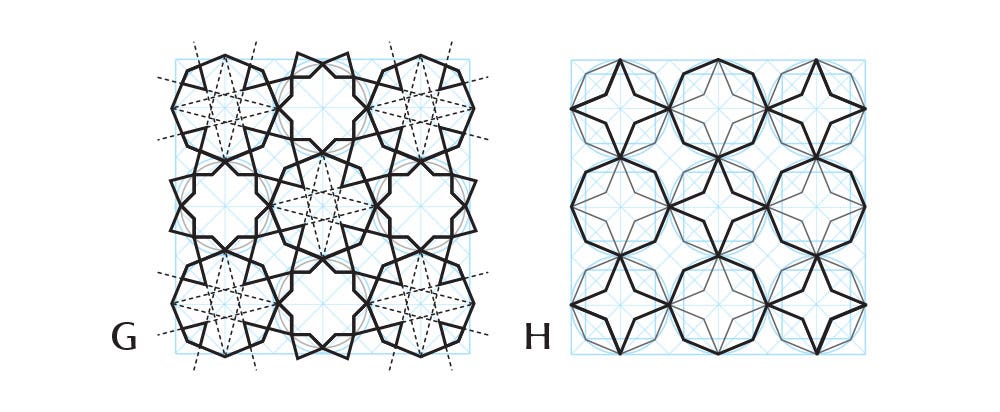

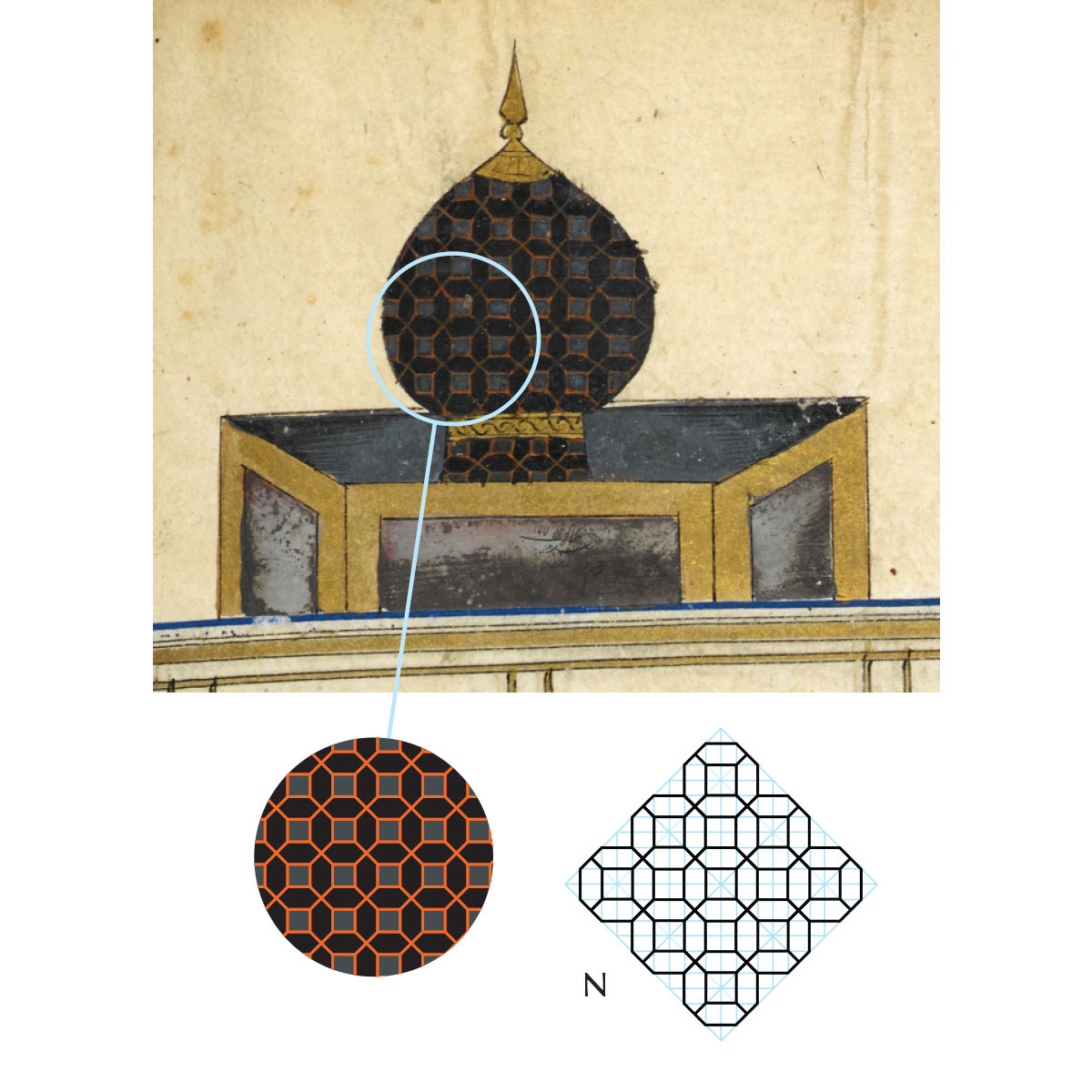

This relatively austere page only offers two patterns, but they’re more complex than any of the others.

Both are based on the grid of squares. I’m not completely sure of G, but as the illustration is done freehand it’s difficult to judge the relative size of different parts accurately. This is close enough anyway.

Here we see the entire pavilion and its immediate environment, meaning more surfaces, and therefore an exuberance of patterns.

Again these are simple derivations of the two basic grids (triangles and squares), which are almost infinitely versatile.

Though this image appears as rich as the previous, fully half of the patterns are based on C, and two are simply hexagons. There’s only one we haven’t already seen:

Finally, the BL manuscript is only really interested in the characters. There’s a pattern on the door, corresponding to J, that is the same throughout all its illustrations, and otherwise the dome is the only locus of such attention.

This concludes our survey of patterns under the Black Dome, to be continued soon under the Yellow Dome. Let me know what you think!

For a more detailed synopsis, see Encyclopædia Iranica.

By order of perceived closeness to the Earth: Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn – and yes I know the sun is not a planet by our modern definition of the word. But the Greek word “planet” translates literally as “wandering [star]” and it referred originally to celestial bodies that could be seen to move relatively to us, as opposed to the “fixed stars” which appear not to – the backdrop of constellations that we know today to be extremely distant stars.

Colour and Symbolism in Islamic Architecture, p281.

Idem.

It’s not my place to elaborate much more on the layers of symbolism, but there’s a very thorough discussion of it against the broader context of Persian mystical symbolism in the appendix of Colour and Symbolism in Islamic Architecture. This book is a masterpiece, but the title tends to mislead in that it’s not a straightforward study of the above; instead it’s a mostly a visual journey through Islamic monuments of the seven climes in question, punctuated with extracts from Haft Peykar, with a particular attention to the craft of creating the seven colours on ceramic tiles. Only the appendix, which is hefty, provides substantial analysis. I specify this because it’s pricey and when I first bought it I felt a bit put off, but after years of revisiting it with growing understanding of what the book was actually doing rather than telling, I treasure it. There is however an interesting paper on the subject that can be freely accessed: “Color Symbolism in Islamic Book Painting” by Imane M. Sadek Abaza. I recommend it because it goes into the complexities of the subject rather than the usual dumbified picture that is usually panned around.

Just added Nizami to my "to acquire" list. I like how the poetry in the first image also appears to resemble the architecture of the building by virtue of its geometric layout. They sure don't make them like they used to!