When I started my research of early Islamic inkmaking, I was pointed to Ghāyat al-Hakīm, a book of magic and astrology written in the 11th or possibly 10th century. One chapter in the book provides recipes to make inks that correspond to each of the 36 decans and are “absolutely necessary for the work of magic or talismans”. Now, for the purposes of a conference that will take place in January, I’ve been tasked with preparing all of these inks. I don’t study magical matters and couldn’t actually tell you what a decan is (other than there are 3 to each sign), but my role is to use my technical experience of the art technology of that time and culture to shed light on these particular preparations. One of these recipes is straight from a writer’s handbook, but most are specific to the Ghāya and have no artistic merit: they can be prepared, but their value is magical, and a calligrapher would have better ways at their disposal to achieve the same or a better result. Which makes them specially fascinating!

When I wrote Inks & Paints of the Middle East, I summarised these magical inks in an appendix. Since I now find myself making them all (if I can), I’m documenting the endeavour in detail. The total number of inks is not actually 36 but around 16 because several serve for more than one decan. And I’m not proceeding in order, but in two and threes that require a similar work process.

Nevertheless, we start with the very first ink: the first “face” of Aries.

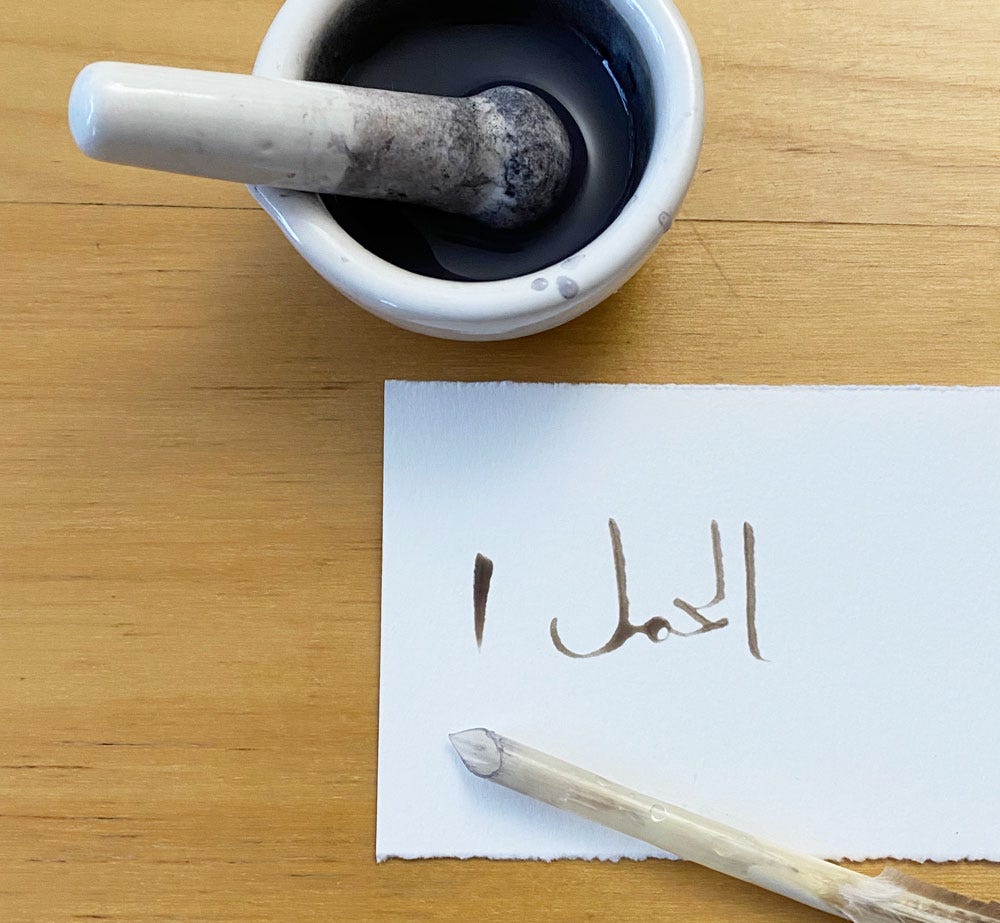

Aries 1

الحمل أولم وجه منه مداده أشقر وصفته أن يسحق العفص الأخضر ناعما ثم كذلك الصمغ والزاج كل على حدته ويكون العفص جزءا والصمغ والزاج نصف جزء ثم يجمع ببياض بيضة ويبندق ويصيّر في إناء ويوثق فمتى احتيج اليه دقّ وحلّ

“Aries: The ink for its first decan is ruddy, and its recipe is finely grind green gallnut then gum and vitriol, each separately, the gallnut being one part and the gum and vitriol half a part each. Then gather in egg white, roll into hazelnut-sized balls and store in a jar. When needed, pound and dissolve.”

Translation notes:

The ink is described as ashqar, which refers to fair but also reddish hair. I opted for “ruddy” because it connects to the reigning custom of referring to brown inks as “red” (aḥmar). It’s interesting to note that ashqar is normally reserved for fur and hair: it’s never used to describe an ink colour by actual inkmakers. We’ll encounter several similar descriptions in other talismanic inks. I don’t know why the lexicon of colour in a magical context is so different, but it’s worth noticing.

I translated zāj as “vitriol” because both words are equally non-specific. Zāj refers to a natural product combining copper and iron sulphates, where the ratio of these two substances affected the final result, from brown to deep black. When they’re being specific, Arabic texts mention different grades of zāj, usually defined by their provenance, and there is no way of working them out now — vitriol is no longer gathered in the copper mines of Cyprus, Persia or elsewhere. Instead, blue and green vitriols are now manufactured as pure uncontaminated products, a headache for historical recreation. However, the description ashqar is a strong clue that this particular zāj can’t have been high in iron, otherwise it could only be black.

So, for this recreation, I used blue vitriol with a small amount of iron mixed in. I also weighed the ingredients: I can’t be certain that the recipe refers to mass rather than volume, but so many recipes specify weight units that I have to assume the unspecific ones carry on in the same system. In this particular case, just eyeballing the resulting amounts, it looks like it wouldn’t make a significant difference if I used volumes.

Once each ingredient is a fine powder, they’re combined together. No chemical interaction happens while they are dry.

The point of the egg white is to make balls that can be dried for easy storage, but its moisture content is enough to activate the reaction…

By the time everything is combined, we can clearly see the ink has formed. And now it’s time to get my hands dirty.

A dried ink is an ink that won’t mould and can be safely carried around, and so “making hazelnuts” was the normal way to wrap up most recipes.

Once the balls are fully dry, I pop them in a jar minus one that I dissolve in water to try out the resulting ink. Here’s the result, brownish as promised.

Intermission

Recreating inks means recreating drawing tools (these inks are intended for drawing magical images rather than writing). The Ghāya doesn’t concern itself with these, but I know from other texts that simply cut quill pens were used for drawing and outlining.

I gathered all these at my local pond during moulting season, and tempered them for later use. Now they’re all getting prepared for the workshop and I’m testing them along with the inks.

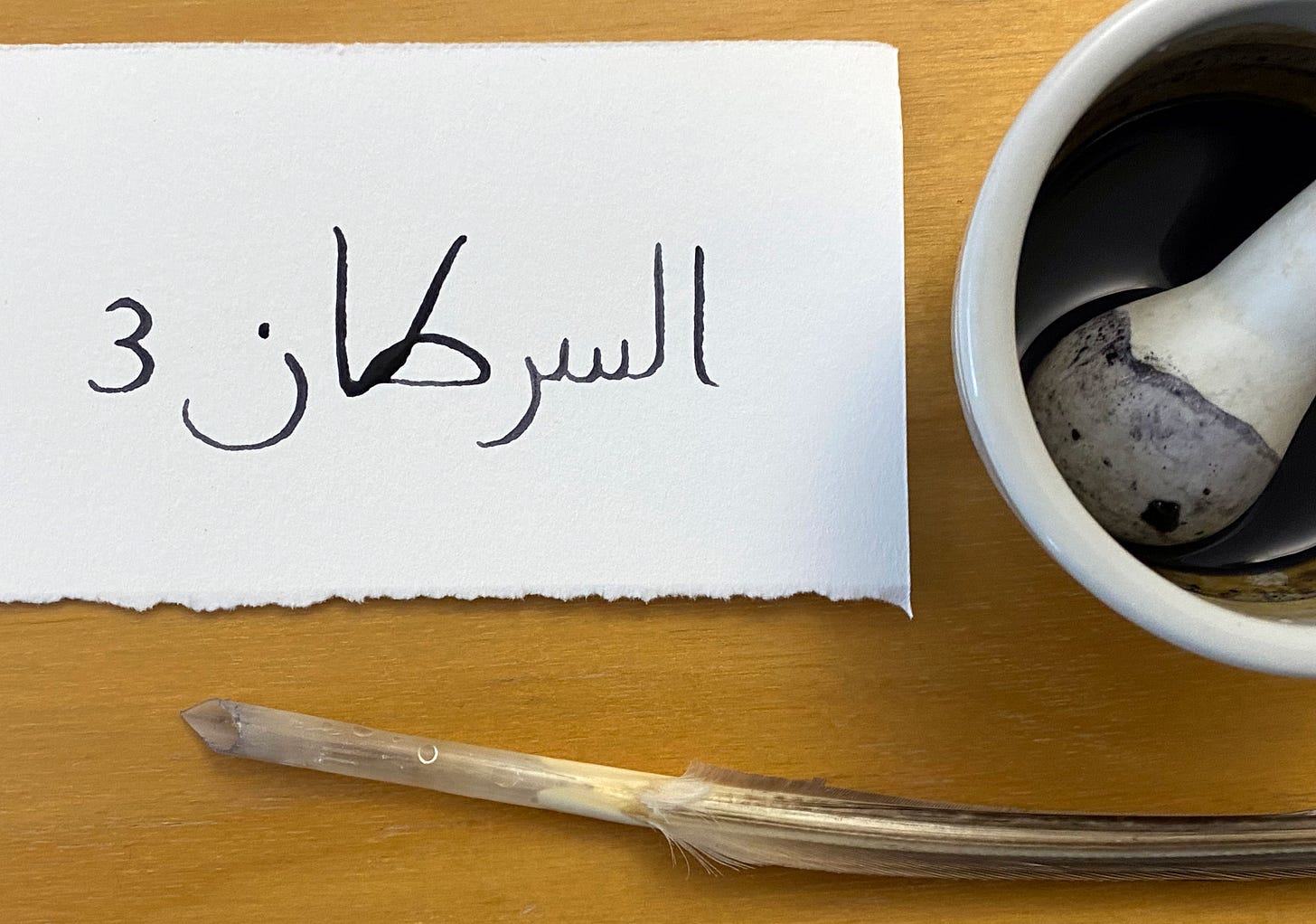

Cancer 3

A little further down the zodiac, the third decan of Cancer calls for a very similar ink:

والوجه الثالث اسود كمداد الوجه الاول الا ان زاجه بالسواء مع العفص

“And [the ink of] the third decan is black like the ink of the [very] first decan, except that its vitriol is in the same amount as the gallnut.”

There’s no mystery, this one increases the amount of iron sulphate so that the ruddy ink turns out a proper black instead. So I repeat the operation with these quantities adjusted.

And here is the result, quite noticeably more black than its relative.

Two inks down, not a bad start to this journey. I hope you found this interesting! Why not joint the conversation and share your thoughts?

decans are a bit obscure... "The so-called Chaldean system [as opposed to the Hindu] makes Mars the ruler of the 1st decanate of Aries then allocates the decanates under the ancient planets in reverse order of apparent motion [ie Sun, Venus, Mercury, Moon, Saturn, Jupiter, then start again at Mars] (Charles Carter, The Principles of Astrology, p21-2)

Hi Joumana! The signs of the zodiac divide the 360 degree circle of the heavens into 12 parts each of 30 degrees. Each sign can then be divided into 3 decans of 10 decrees each