This series continues, but before I plunge in I wanted to let you know about a Kickstarter campaign I just launched to fund the production of my next artist book: The Book of Abdjad. The book is a big boy but there are a number of digital and physical rewards, so if you’re interested in early Arabic/Kufi scripts, numbers, old writing systems, or rare/handmade books, do have a look!

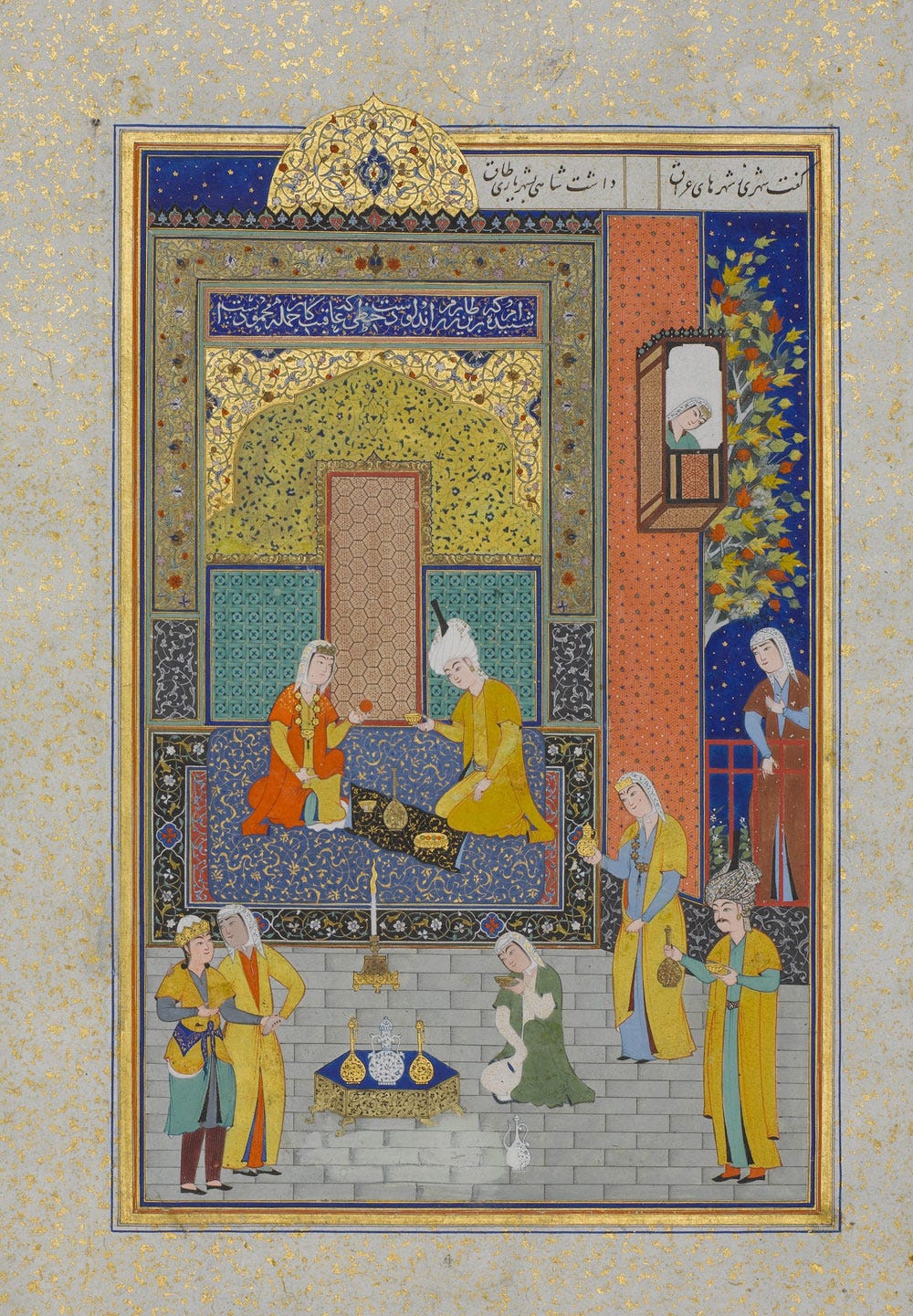

We’re continuing to look at the details of the many series of artworks that were inspired by Haft Peykar, the epic poem that tells of Shah Bahram and his seven brides. I gave a lengthier introduction to it in part 1 (Patterns under the Black Dome) and described how this romantic epic is also a barely veiled tale of initiation.

Here are now the images1 for the second stage of Bahram’s journey. Each is linked to its source page where you can zoom in on the fine details. You might want to read this post in a browser rather than email so you can see the enlarged images.

The Yellow Dome

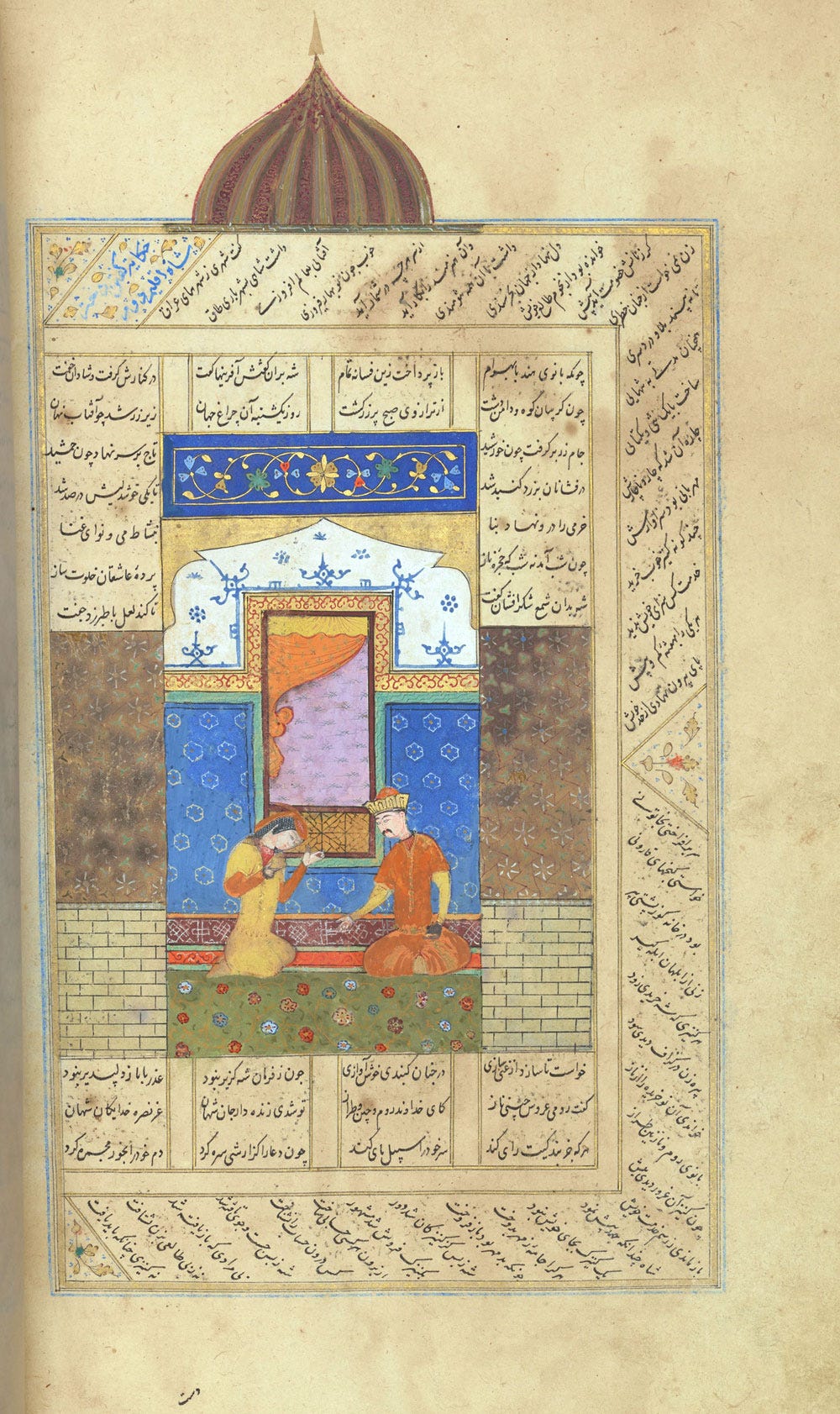

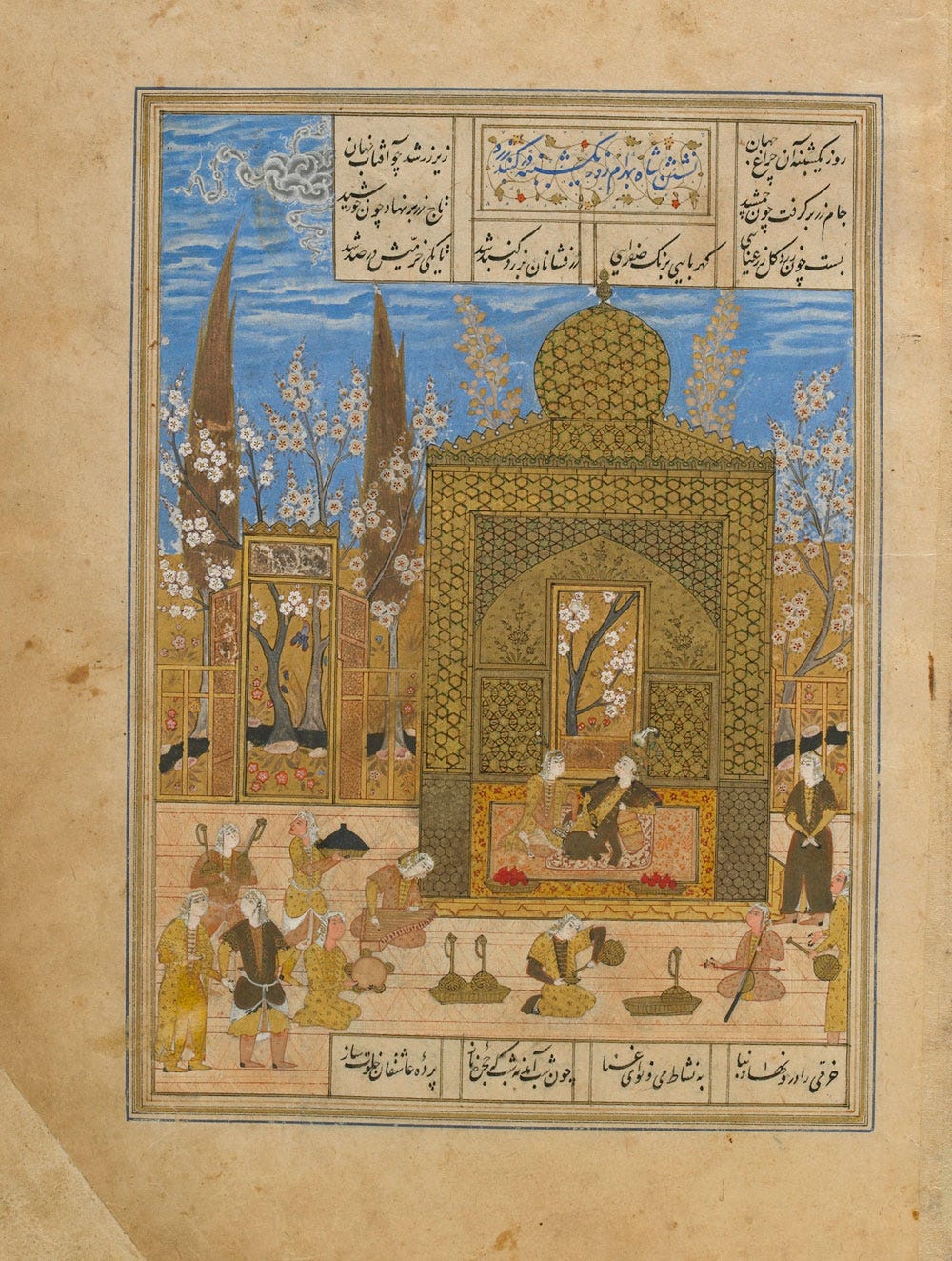

On Sunday, Bahram visits Homāy, Princess of Rūm, clad in Yellow, under the sign of the Sun, Lord of Gold.

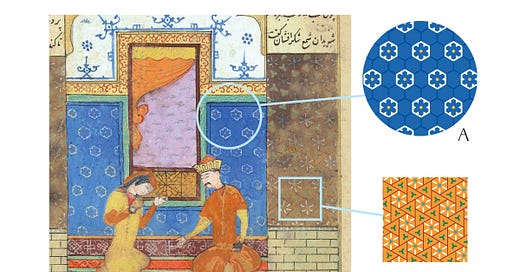

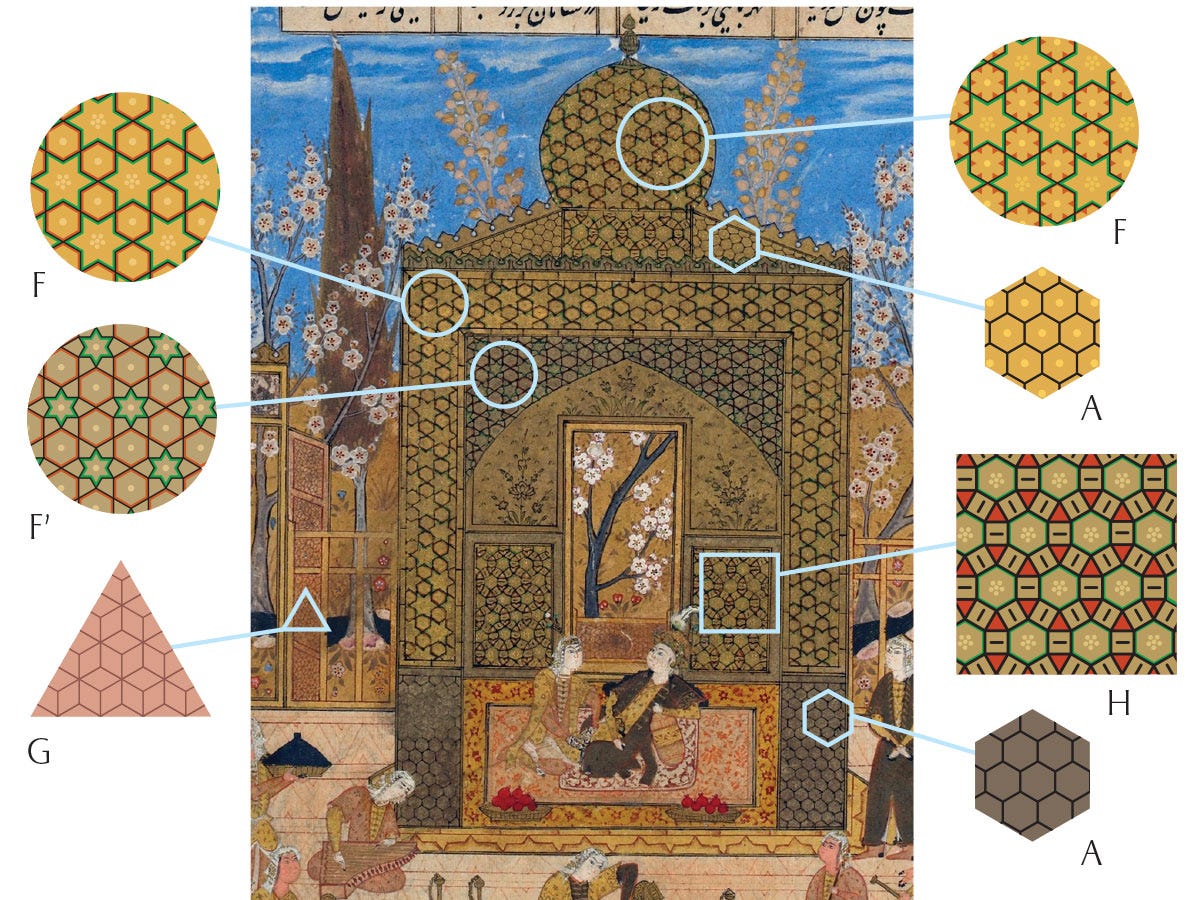

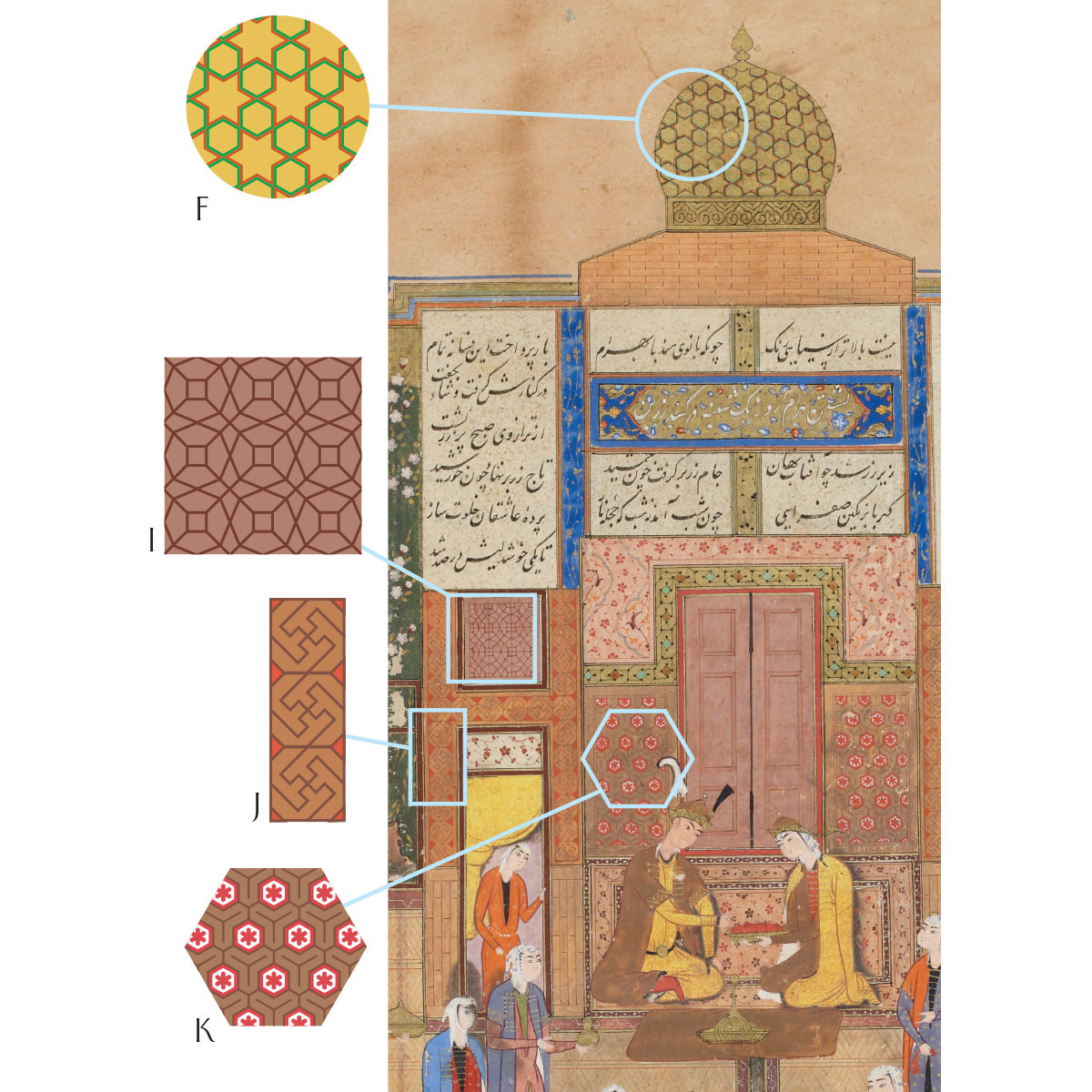

This manuscript again limits itself to two patterns, but they’re not simple repetitions of the Black Dome ones.

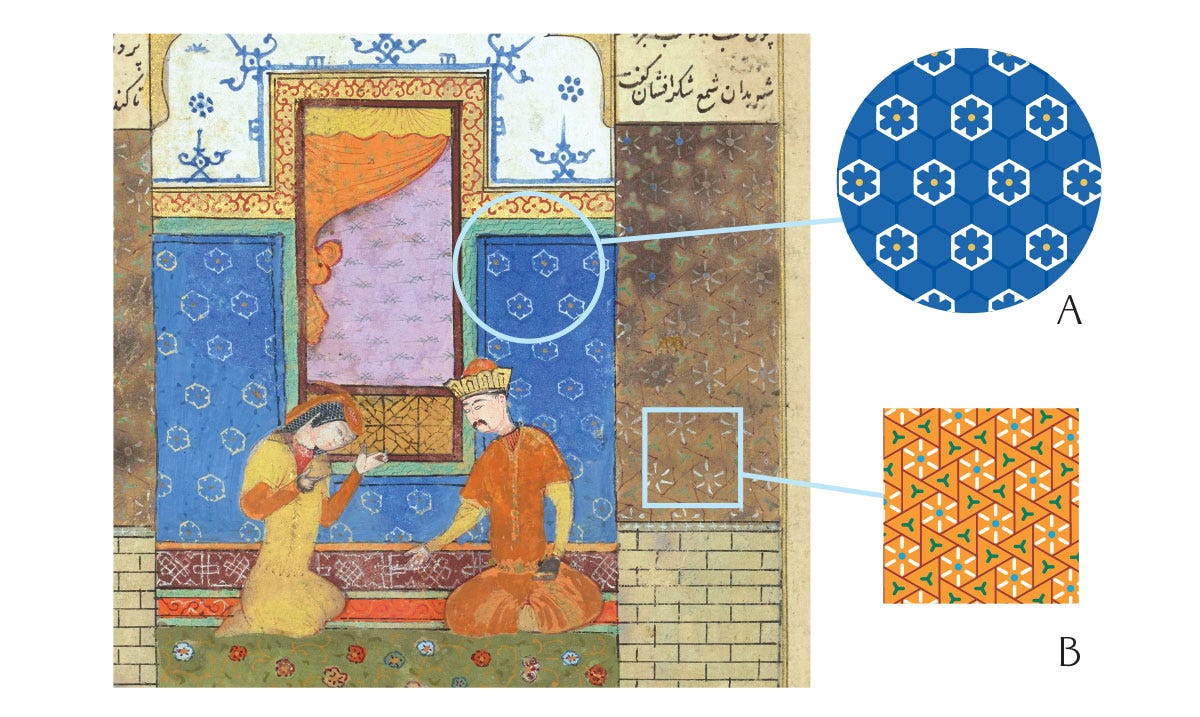

Both are derived from a simple grid of triangles2. B shows use of and damage caused by verdigris, which I’ll talk about more under the last image in this post.

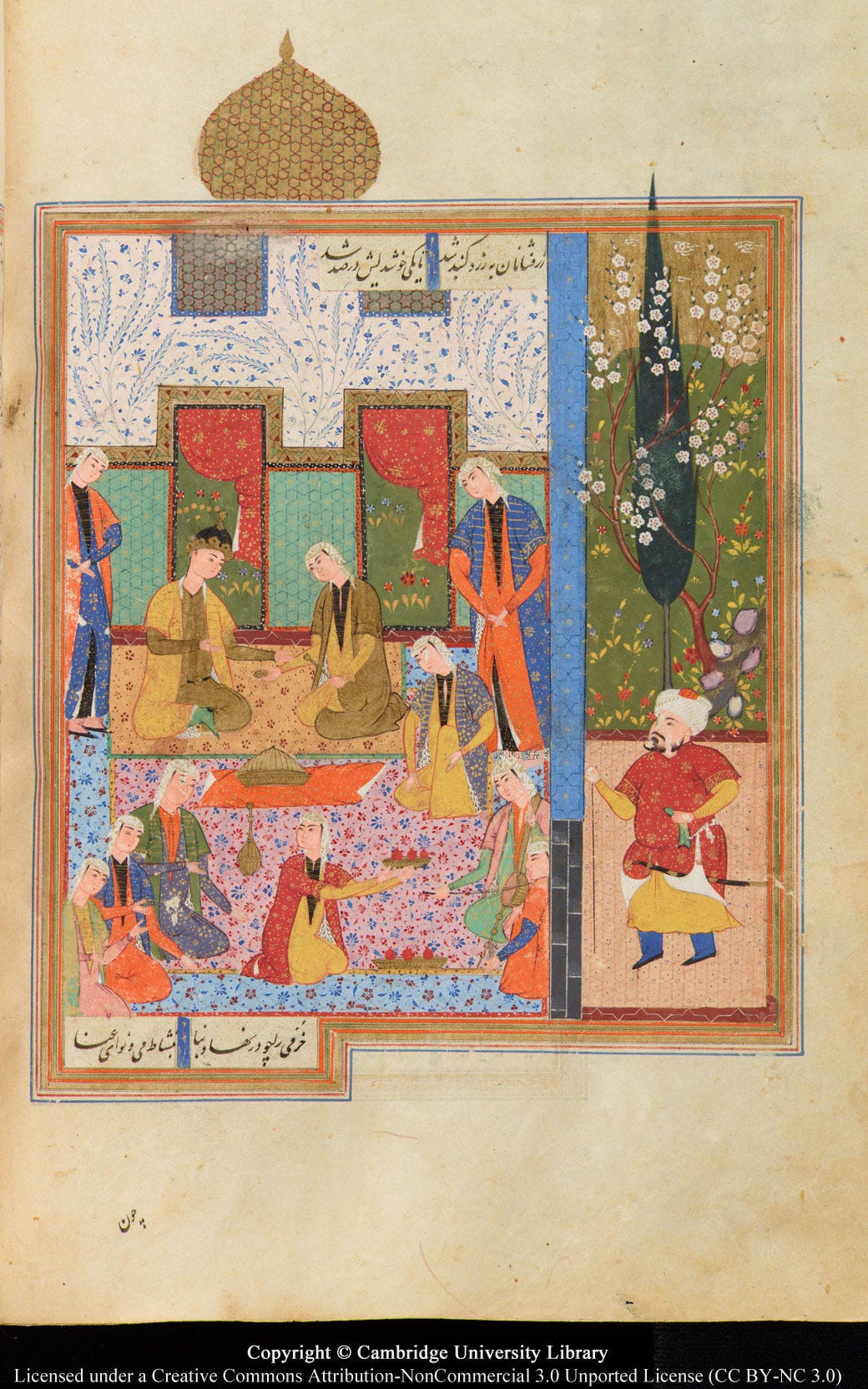

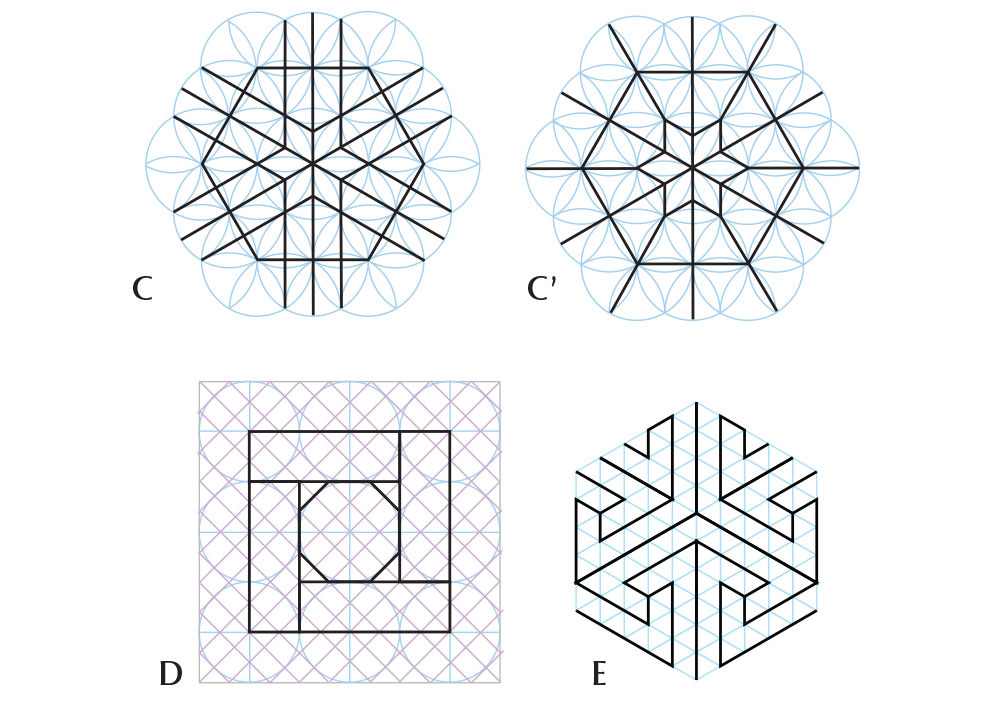

Here, C and E are exactly the same as previously, but C’ is a new derivation and D is something wholly new, I have never seen it before. And see: the artist had used shading quite deliberately to show dimensionality, that one shape weaves under the other. To go to such lengths on this tiny scale simply blows my mind!

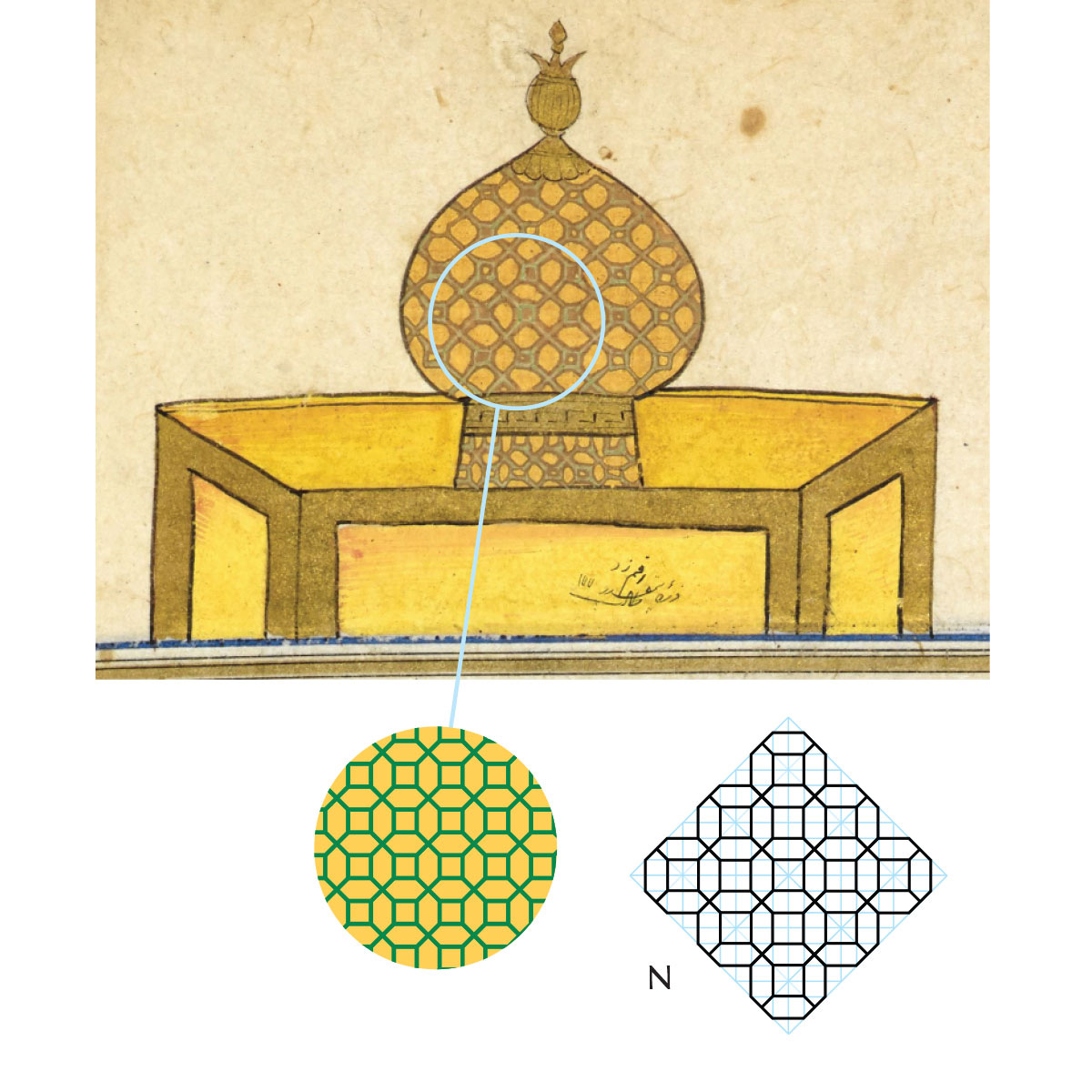

It turns out that D is simply a clever drawing of the same grid of squares that usually yields a basic tiling pattern of octagons separated by smaller diamonds. You have probably seen it, it’s awfully common for bathroom floors and even outdoor tiling in some places. This iteration is very intriguing!

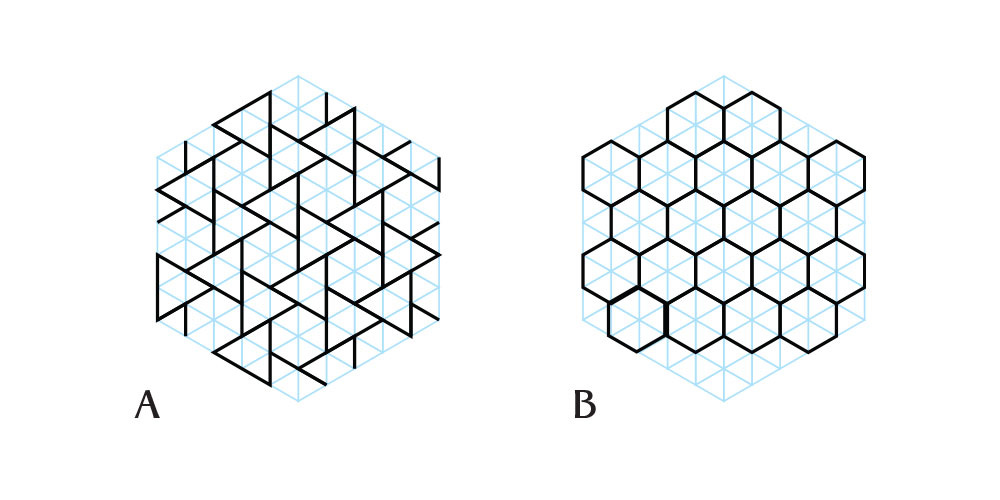

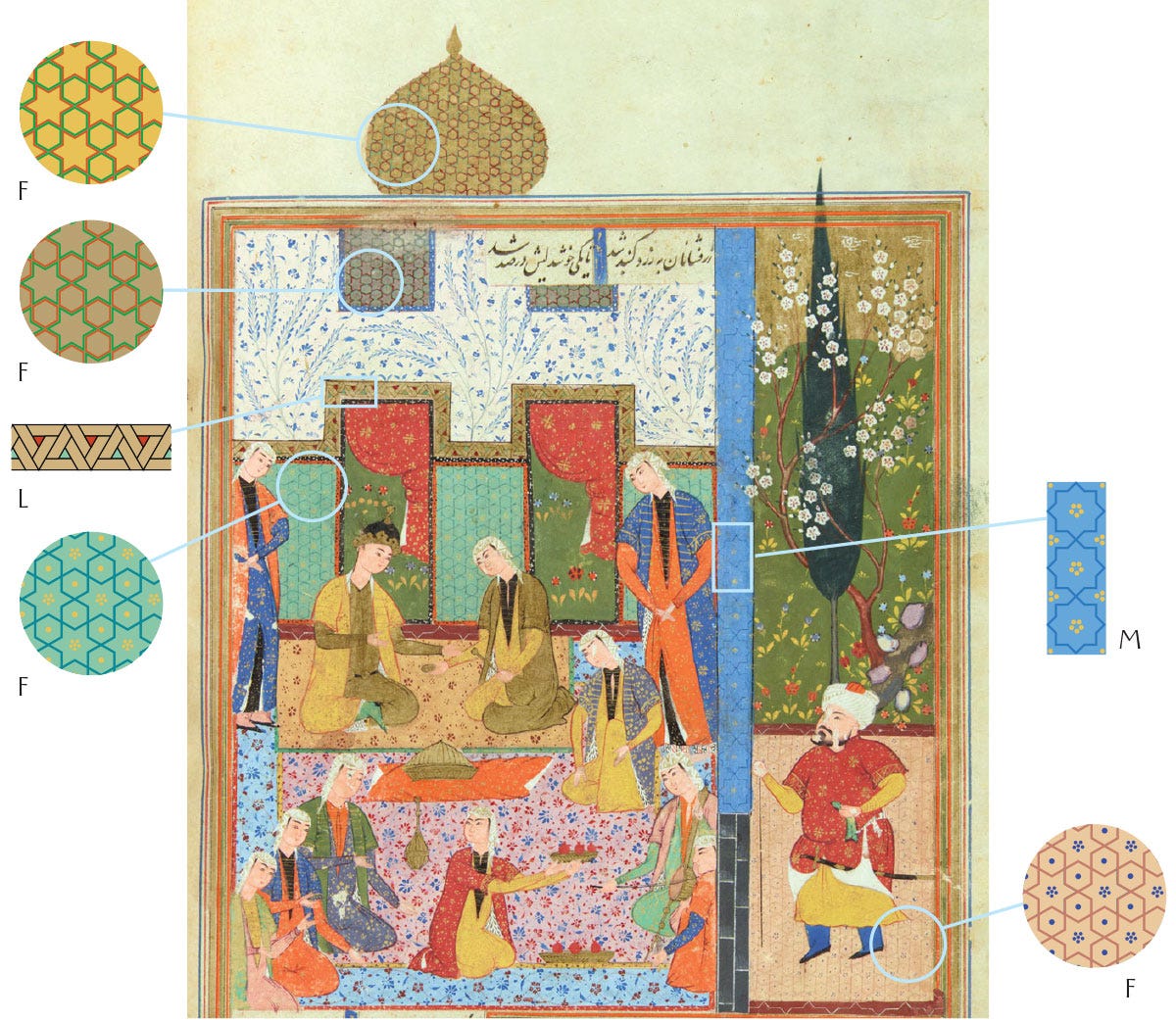

The artist for this manuscript seems to have given up on the intricacy of the patterns he drew for the Black Dome, and instead multiplied simpler patterns. A close examination of the illustration shows small gold dots, single or in group, everywhere. Since all of these patterns are painted in gold, I believe these dots are made by simply impressing them with a pointed burnisher, which creates a small shiny dot in the midst of the more matte gold. This simple technique is still common today. But they could also be painted on, in which case they appear shinier because the gold is simply more concentrated there.

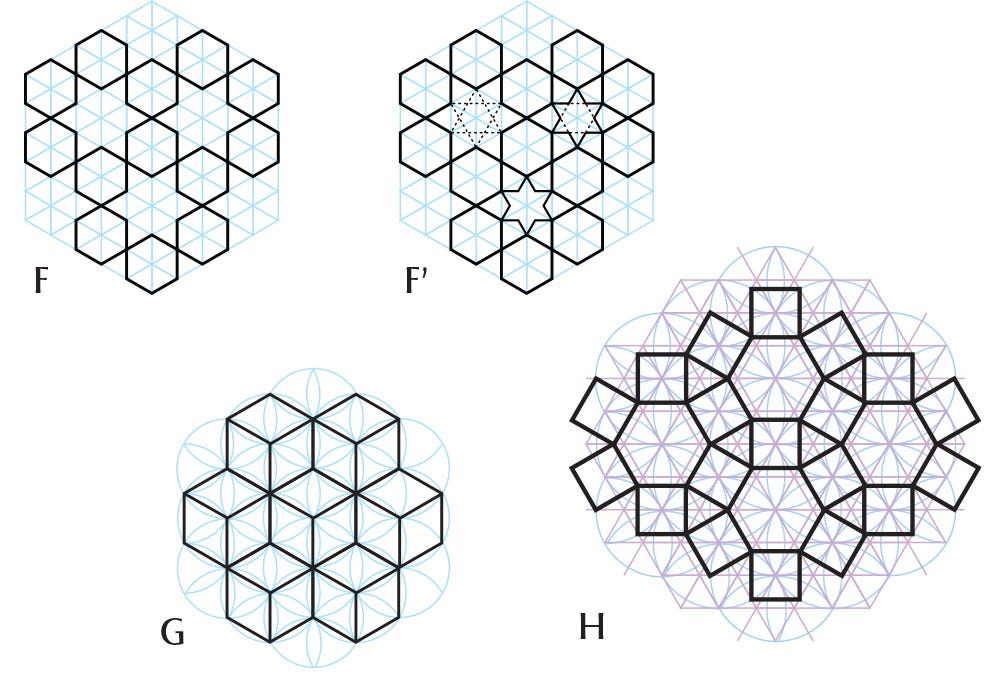

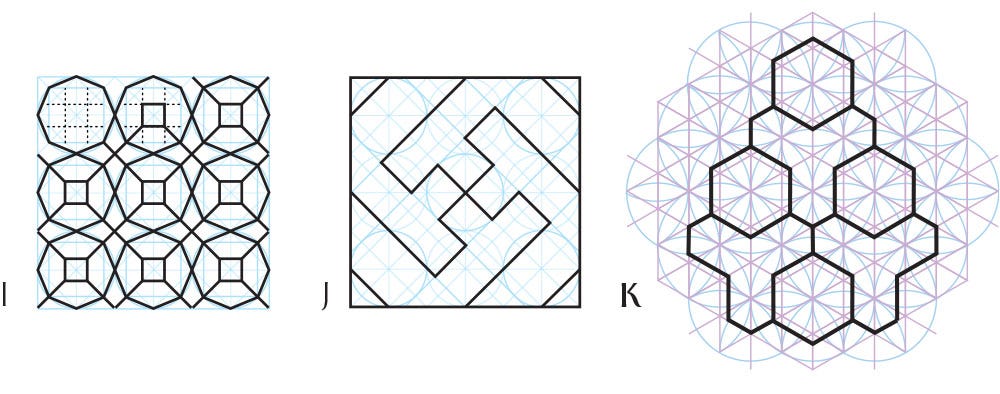

We have seen H before, but the shapes were divided differently, to create three-armed shapes – see K below.

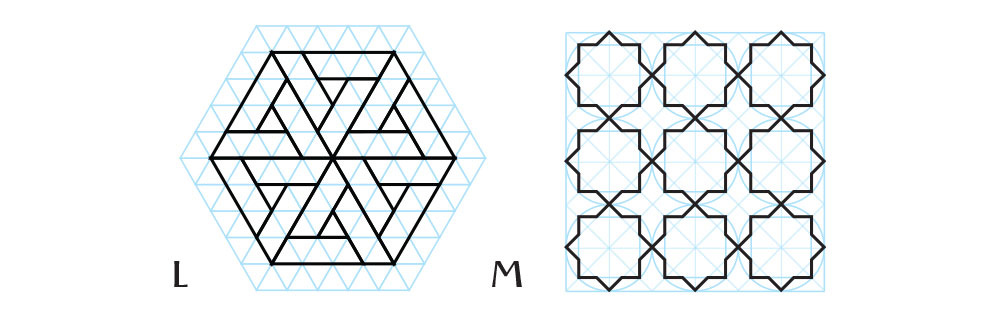

The hexagrams/hexagons pattern (F) with red and green outlines is remarkably consistent between three of our manuscripts. It’s quite a specific palette and I can’t speculate as how it got to be a thing (for instance, is it based on real-life metallic plates or ceramic tiles that these artists could observe? Or just an artistic convention spread by one school of painting?), but it’s interesting to note it is a thing.

Another new pattern is I: though it looks so much like a version of C, it is in fact based on a grid of squares.

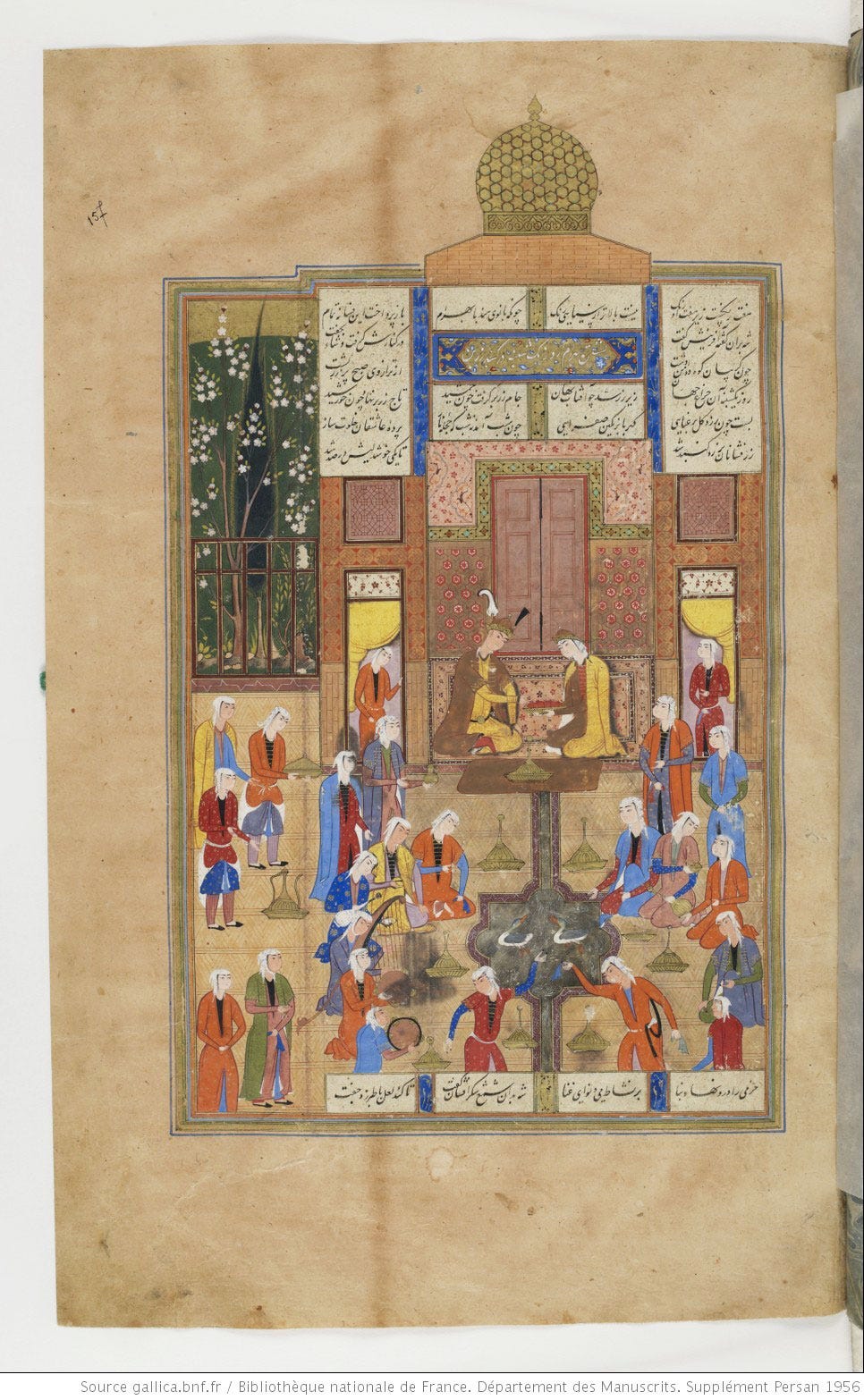

No new patterns here, but the colour palette is unusual and quite delightful.

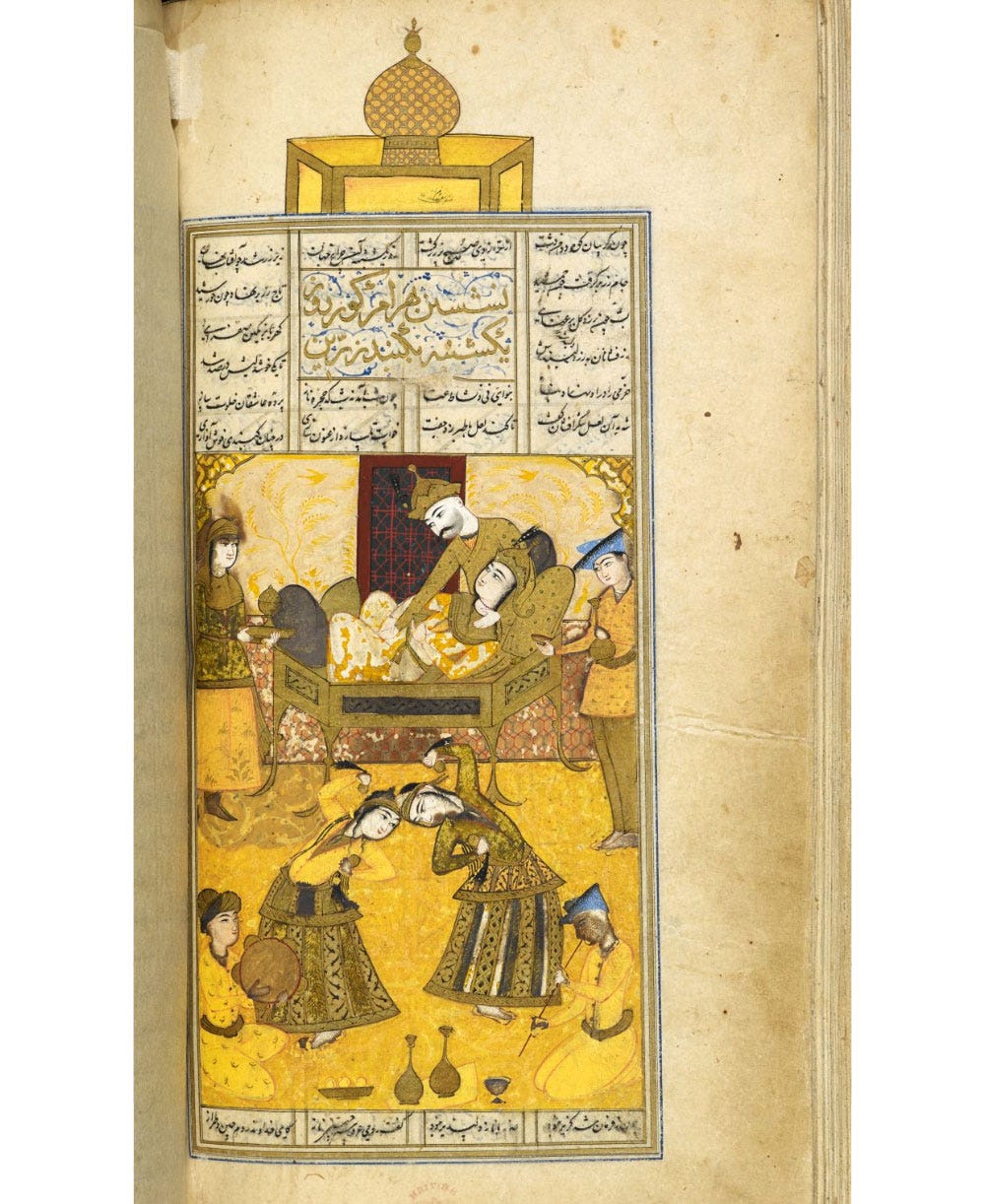

It amuses me that some people still cling to the simplistic notion that Islam forbids portraiture, when parts of the Islamic world not only enjoyed it, but got up to the kind of naughtiness above. As ever, the reality is infinitely more complex than the propaganda.

This pattern is the same as was used on the Black Dome, but there’s something interesting here. If the linework looks strange and intricate, it’s not actually by intention: a closer look shows traces of green surviving in the strokes. What we have here is degraded verdigris: the lines were originally bright green, but this capricious pigment deteriorated over time and left behind the burnt halo that looks so unusual.3

That’s all for today, the next installment will be under the Green Dome…

The sources of these images are the following manuscripts, from the oldest to the newest:

Chester Beatty Library, Per 171 (AD 1492, AH 897), unknown artist.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 13.228.7.8 (AD 1524, AH 931), painted by Shaikh Zada.

Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art, F1908.271 to 277 (AD 1548, AH 955), unknown artist

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Départment des Manuscrits, Supplément Persan 1956 (AD 1560, AH 965), unknown artist

Cambridge University Library, MS Add.3139 (17th c. AD, 11th c. AH), unknown artist.

British Library, Add MS 6613, ff138v-196r (AD 1671, AH 1076), painted by Ṭālib Lālā.

Reminder that if you’re interested in learning to draw these patterns, I offer step-by-step tutorials in my print-at-home booklets The Grid of Triangles and The Grid of Squares available here.

The usual disclaimer applies – properly speaking I should look at the physical page before I attempt to identify a pigment – but the palette of pigment in this culture is fairly small and verdigris leaves burn marks like nothing else, so I can confidently spot it (or what’s left of it).

The way the interiors are designed to be so multifaceted is amazing. I really like all the varied patterns, and how on the wall they are both haphazard and yet ordered. As a writer, it really stimulates the imagination: I don't doubt my literary predecessor counterparts in the Islamic world felt similarly.