The Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge is currently hosting the first major exhibition of Palestinian embroidery in the UK for over 30 years, curated by Rachel Dedman. It’s free to visit and open until October 291. I travelled up especially and recommend it to anyone within reach! Meanwhile it’s my pleasure to share details of the beautiful work on display, as I did a few months ago with the Samarkand exhibit in Paris. They’re actually very interesting to see closely together, as there certain similarities.

I’m not reproducing the exhibit’s meticulous organisation and detailed labels, but including concise commentary focused on technique and motifs, based on the exhibit and other references. Suggestions for further reading are included at the end of the article.

General notes:

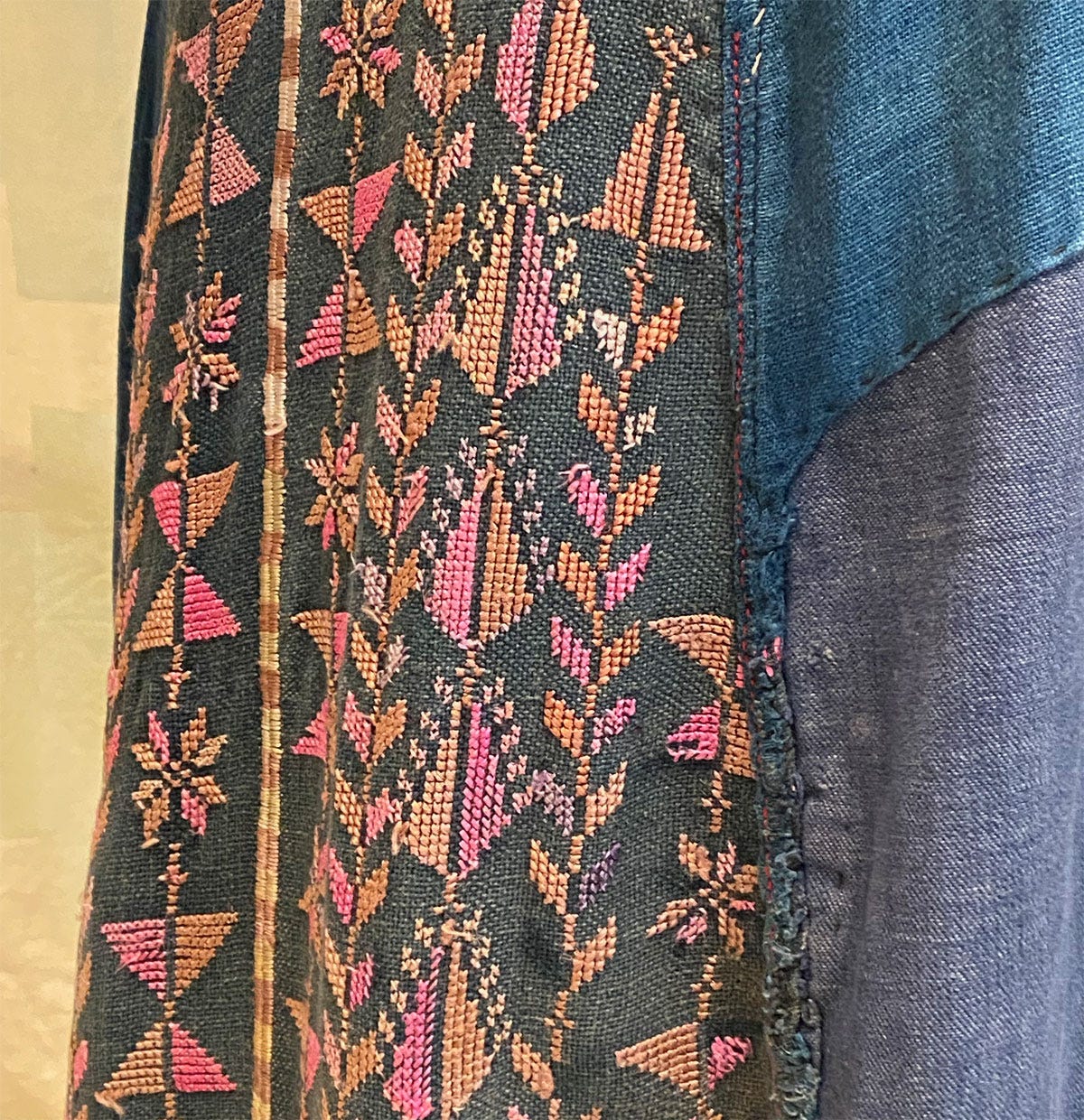

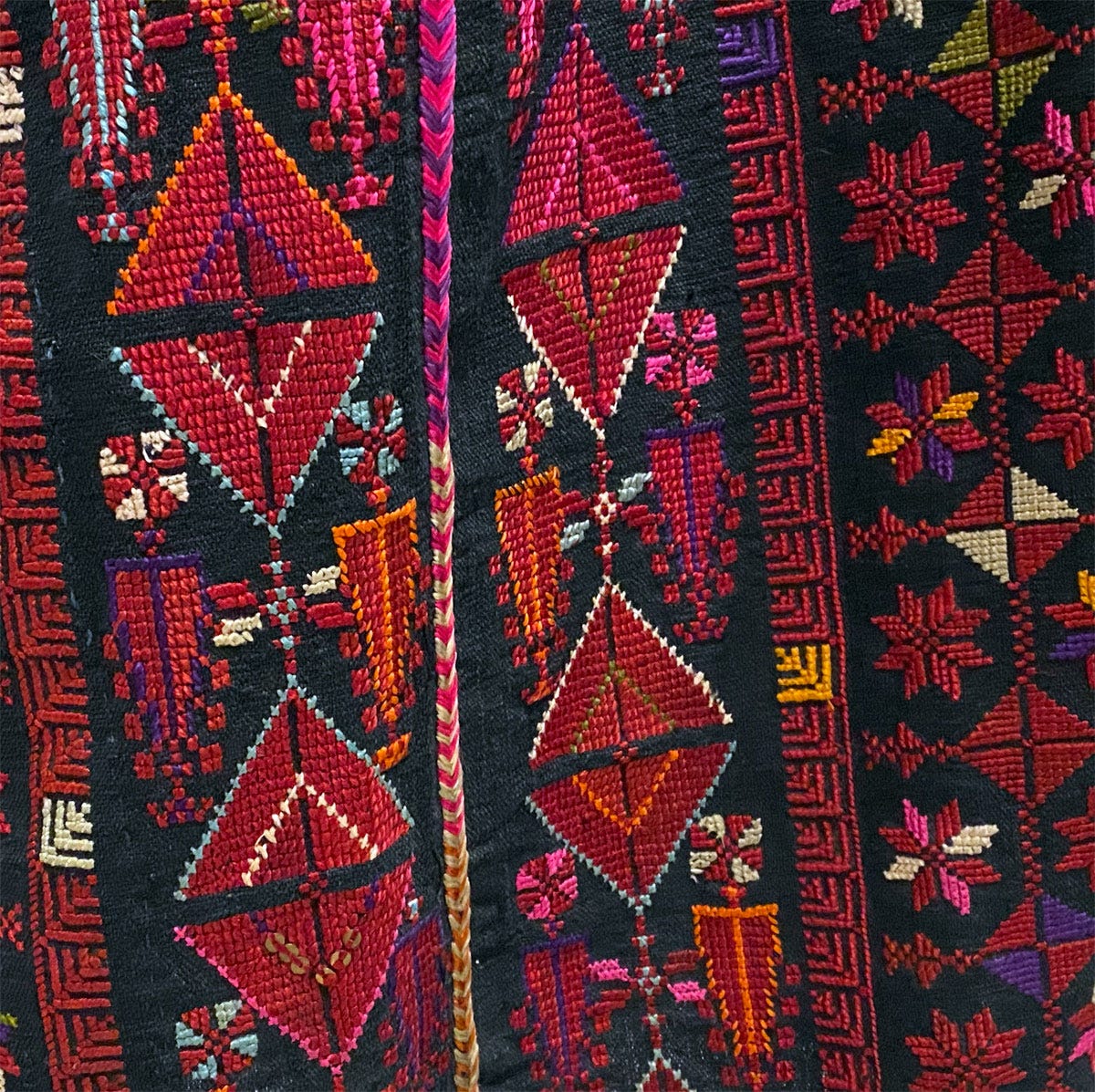

Palestinian embroidery is natively known as tatreez تطريز (which simply means “embroidery” in Arabic), while the cross-stitch that is at its core is called fallaḥi فلّاحي , because it’s associated with agricultural workers and village life. City women didn’t tend to wear these dresses.

A single motif can have several different names, as well as stitch variants.

Up until about 1930, the threads were dyed silk from Syria, and the colours from natural sources: indigo نيل for blue, kermes قرميز and madder roots فوّة for red, and yellow ochre مغرة تراب for yellow. Each area showed a preedilection for a particular shade of red.

It’s customary to introduce an imperfection of some sort – the wrong colour, missing stitches – in every garment in order not to tempt the Evil Eye (which among other things is attracted to outstanding beauty).2

As a creative tradition that was practiced by women and was handed down from mother to daughter, the only record of tatreez is the surviving work itself. But as it belonged on everyday dress that would be modified and reused until completely worn out, the oldest surviving examples don’t go further back than the nineteenth century3. By the first half of the twentieth century, distinct trends can be attributed to different regions of Palestine, with towns and villages each having their own signature.

Historical dresses

Ramallah رام اللّه

Dresses of the area could be “white” (thob abyaḍ ثوب أبيض ) made of undyed cotton or linen, as well as the usual “black” (thob aswad ثوب أسود ) dyed with indigo. Sometimes only red thread (typically wine red) was used for the embroidery.

Jaffa يافا

Hebron الخليل

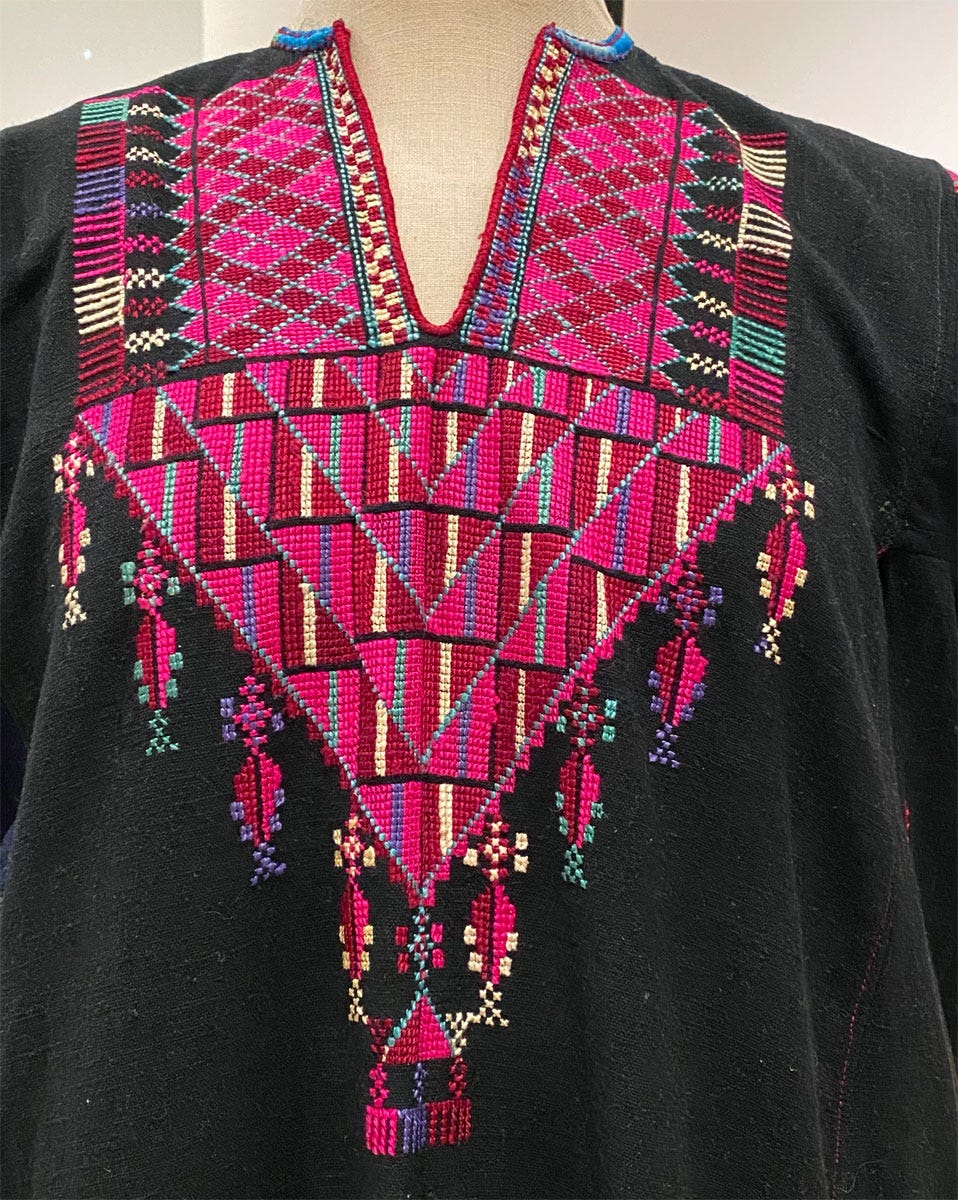

Bethlehem بيت لحم

Famous for its use of taḥrīri تحريري (couching): silk or cotton cord is coiled on the fabric and stitched in place. Couching with gold or silver thread (qaṣab) is called rasheq.

Jerusalem القدس

Nablus نابلس

This area was famous for fine embroidery with small, perfect stitches, and the practice of rasheq with white thread.

Tubas

Gaza غزّة

Galilee الجليل

Beduin dresses

Post-Nakba: The New Dress

Everything changed with the Nakba, with people fleeing their native villages to end up abroad or thrown together in refugee camps, never able to go home. From the point of view of the craft, that meant a complete disruption of lineages, either by total interruption or by intermingling, and eventually, when women turned to embroidering items to sell as livelihood, the threat of cheapening and standardisation. The exhibit includes examples of new dresses – embroidery born of refugee camps, prison, revolution and even prosperity (for the lucky few who ended up working in rich countries), and also tatreez-inspired contemporary art pieces, which I had to leave out of this already overlong piece.

I’ll end with this screenshot from Maeve Brennan’s movie The Embroiderers (2016), featuring five embroiderers interviewed in their homes in Palestine, Lebanon and Jordan:

Further reading:

Threads of Identity: Preserving Palestinian Costume and Heritage by Widad Kamel Kawar. Widad Kawar is considered the patron saint and guardian angel of Palestinian dress but also other traditional dress from the region, and much of the exhibit comes from her own collection.

Palestinian Embroidery: Traditional fallahi cross-stitch by Widad Kamel Awar and Tania Tamari Nasir. Available as a free download from the Tiraz Centre.

Palestinian Costume by Shelagh Weir. Can be “borrowed” online here.

Labour of Love: New Approaches to Palestinian Embroidery, curated by Rachel Dedman. This is the publication for the original exhibition which took place near Ramallah in 2018. It’s tricky to find but can be bought online here. The briefer exhibition guide can be downloaded as a pdf.

Palestinian Embroidery Motifs: A treasury of Stitches 1850-1950 by Margarita Skinner, in association with Widad Kamel Kawar. As the title suggests, this book (which I own) is focused on surveying stitches and their various names. Several of the exhibition dresses are featured in it.

The instagram account of Wafa Ghnaim: tatreezandtea. A dress historian, Wafa is a researcher at the Met Museum and a curator at the Museum of the Palestinian People in Washington, D.C. She’s also a practitioner of her ancestral craft and shares a great deal of imagery, history, tips and sometimes downloadable resources, along with teaching it and selling supplies. There are lots more references listed on her website.

Note it will then travel to Whitworth, The University of Manchester, where it will be open from 24 November to 7 April 2024 – so there’s still plenty of time to catch it in the UK!

Traditions around the “eye of envy” are still going strong: in much of the Middle East, even in urbane Beirut where I grew up, the language doesn’t even accommodate praise and compliments separately from customary sentences to avert the evil eye. I’ve discussed the deliberate introduction of imperfection in a context of piety in Walls That Speak, Part 2.

There’s no question its origins go back much, much further. In 1989 a group of naturally mummified bodies were found in one of the many caves of the Qadisha valley in Lebanon. They were 13th-century Christian refugees and wore clothing with cross-stich patterns in silk thread. These are the only known examples of everyday medieval wear in Lebanon, and they are displayed in the National Museum – you can see pictures of them here but be aware they show human remains. I mention this because both the dress type and embroidery technique are evidently related to Palestinian tatreez, despite the centuries of evolution in-between. This tradition did not survive into modern times in Lebanon by the way, possibly due to the adoption of Ottoman wear early on.

Another wonderful insight of yours! Thank you so much for writing this, Joumana! I started my day with your article and cannot express my gratitude enough! Well curated and beautifully explained, and certainly one of the most thoughtful and clear pieces I read about the history of Palestinian embroidery.

Wow, Joumana, I’ve found this only now - 14 Jan 2025! and so glad to see it. Overwhelming it is; all these lovely clothes with incredible embroidery; so happy to have found this article and I’ve saved it so I can read it in the morning - well, later this morning, as it’s after 1 a.m. here in Sydney. In sight of what is happening now in Palestine, I can only hope that there have been more of these beautiful clothes saved … somewhere else in the world. Thank you for all you have done to give this to us.