I’ve just returned from Paris, where I went to see this sumptuous exhibit, at the Institut du Monde Arabe. Sadly it ends on June 4, so today’s post is a visual feast from the show.

Samarkand, Bukhara, Tashkent, in modern-day Uzbekistan, belonged to the Empire of Khwarezm and were prominently part of the Silk Roads. The rich history of the region is barely known in the West and I won’t attempt to summarise it, but for the purpose of this show, suffice it to know that this powerful and expansionist Turkic-Persian empire was entirely brought down by the Mongols in 12191 but the cities returned to splendour under the reign of Timur (Tamerlane), patron of the arts, whose grandson Ulugbek in turn championed astronomy and mathematics. Samarkand became a world centre of medieval science. After more conquests and another period of decline, the Emirate of Bukhara (1785-1920) nurtured a renaissance2 of traditional Uzbek crafts at the court; this is the subject of the exhibition, which features astonishing surviving examples of fashion and jewellery from the collections of Uzbekistan museums.

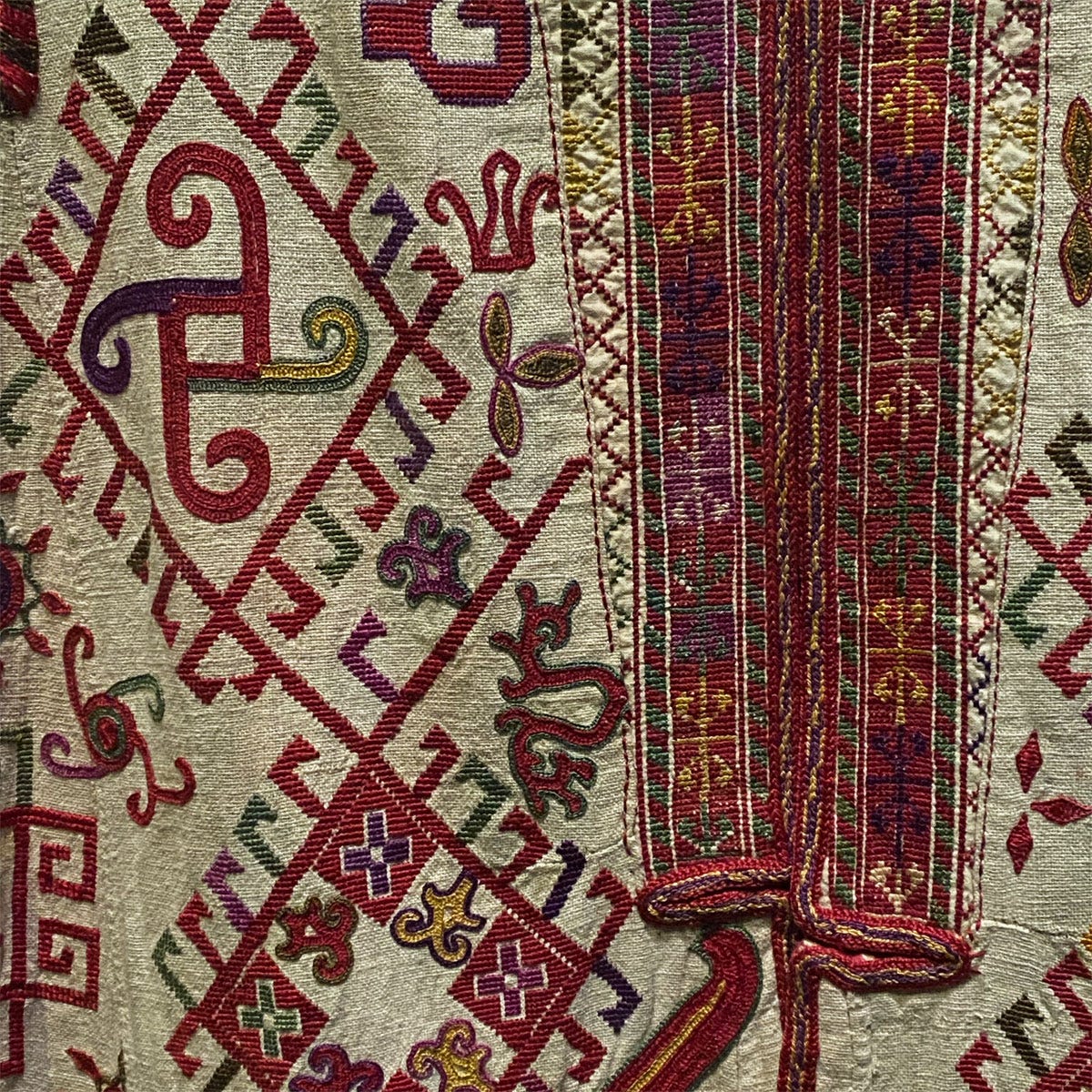

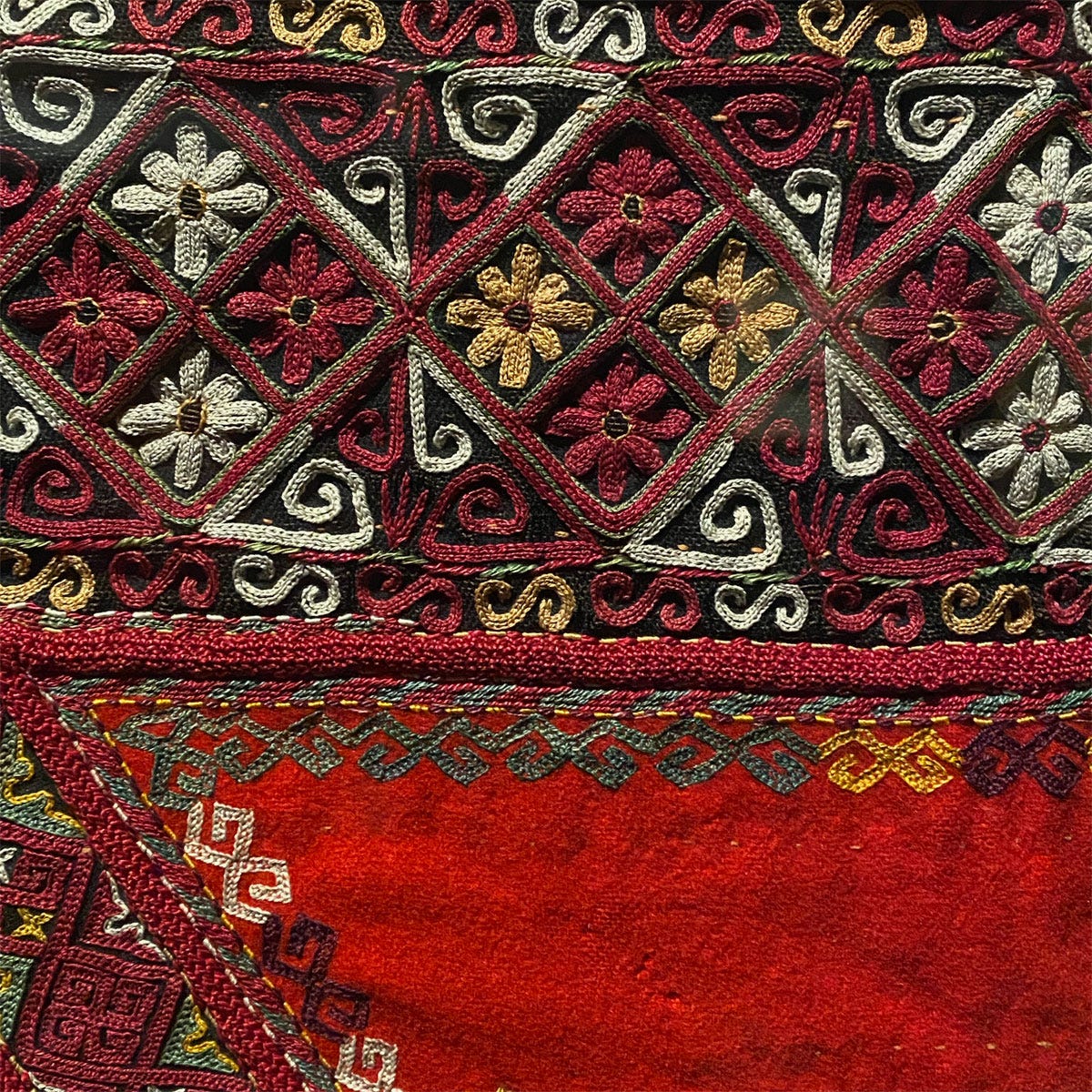

All of the following pieces date from somewhere between the late 18th to the early 20th centuries, and I include more detail when I have it. Rather than showing the full robes, I’m offering close-ups on the detail of the craftmanship…

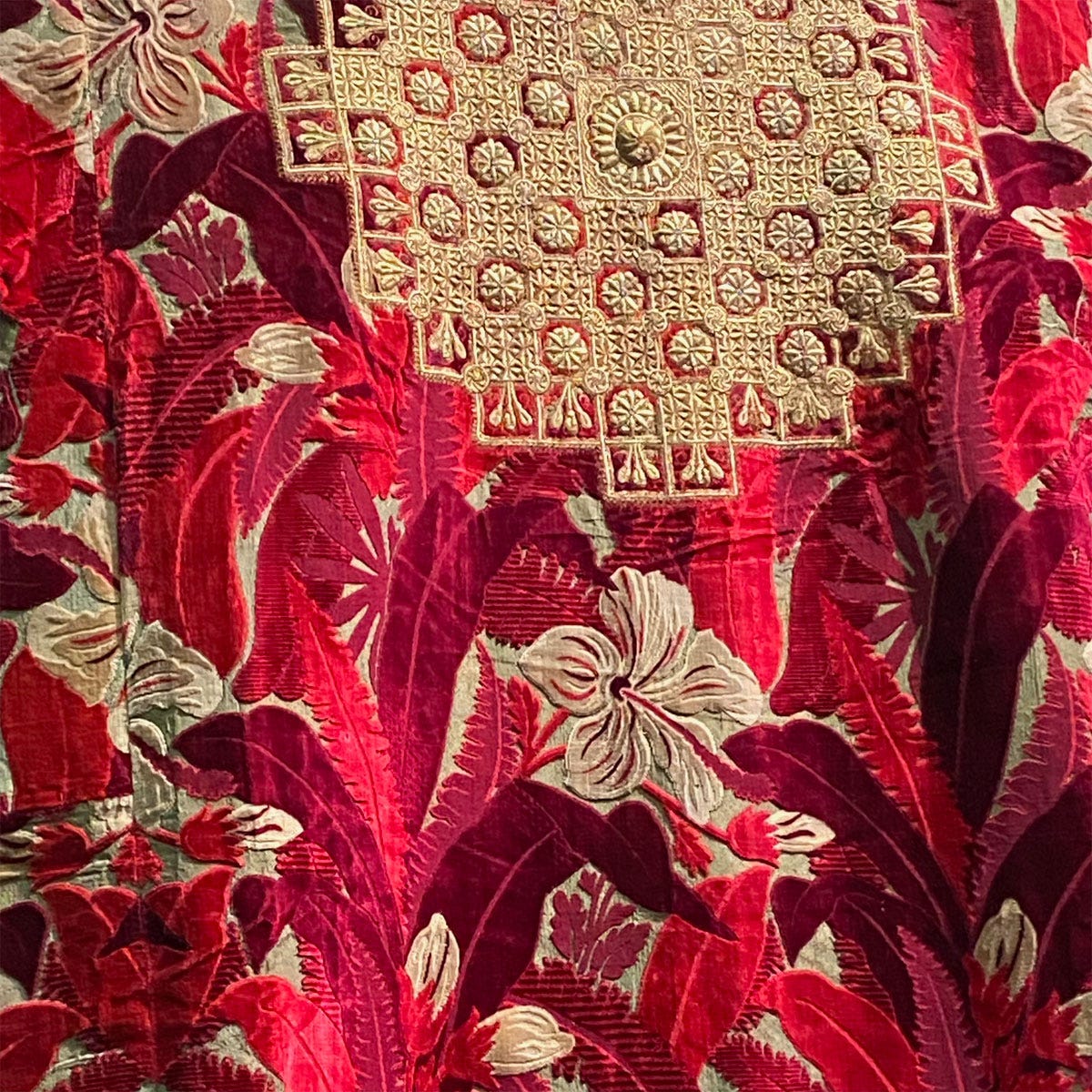

Chapan: Also known as khalat, this was the most important item in men’s wardrobe, a long loose-fitting kaftan that was worn over several layers of clothing. The finest chapans at the court were made on a base of silk velvet (bakhmal) embroidered with gold. Those worn by the emir and its close entourage were made in the exclusive darkham style, which features a interlaced vegetal pattern covering the entire garment.

The art of gold embroidery, known as zardozi, was strictly practiced by men due to a belief that the touch or breath of a woman would tarnish the metal3. The thread used was either soft-spun gold (kolobutan) or drawn gold thread (sim). The court of Bukhara was famed for the technical brilliance of its embroiderers, and gold-embroidered chapans were given as diplomatic gifts.

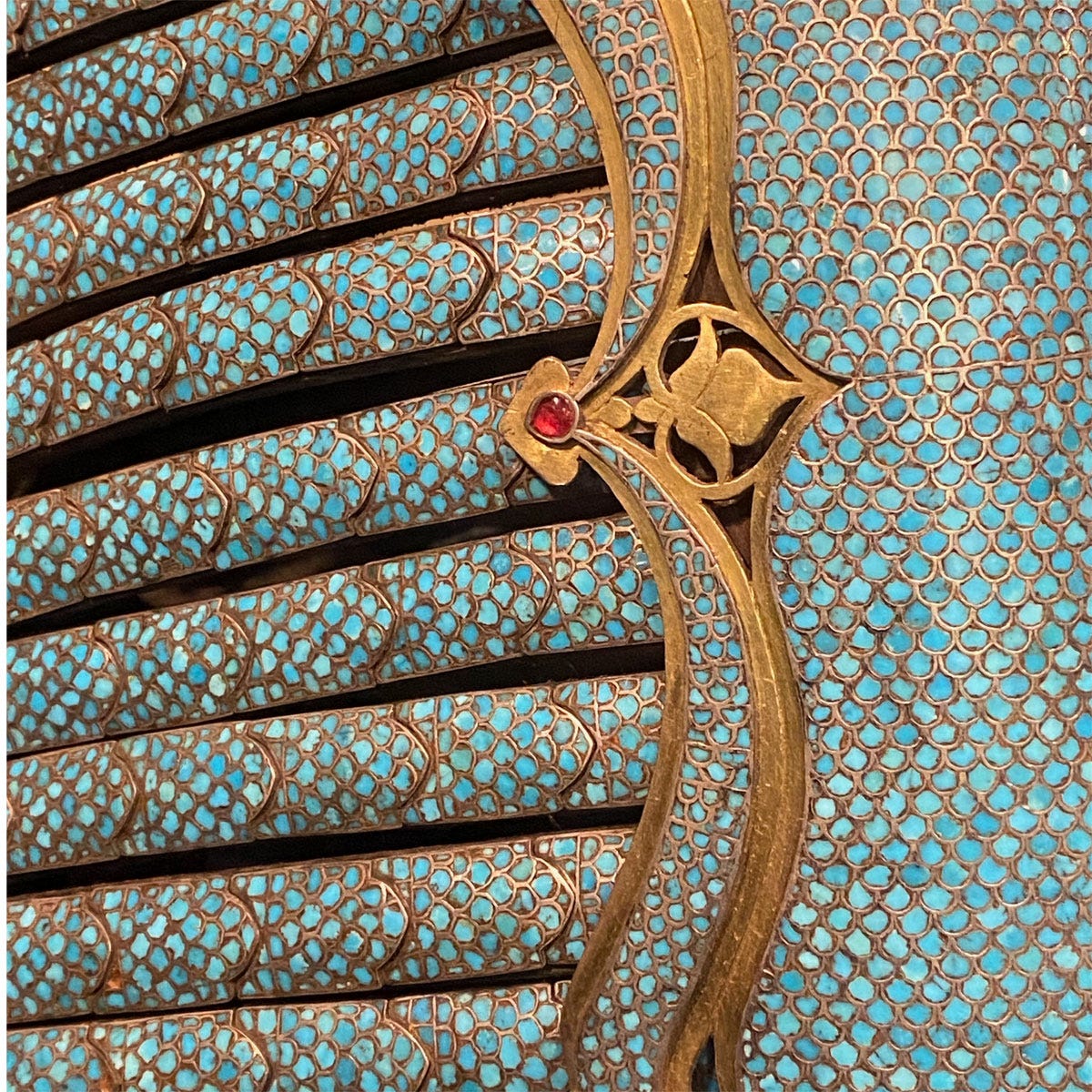

Horses held prize of place at the court, and their accessories, from saddle rugs to mane ornaments, were every bit as richly worked as the garments of their riders.

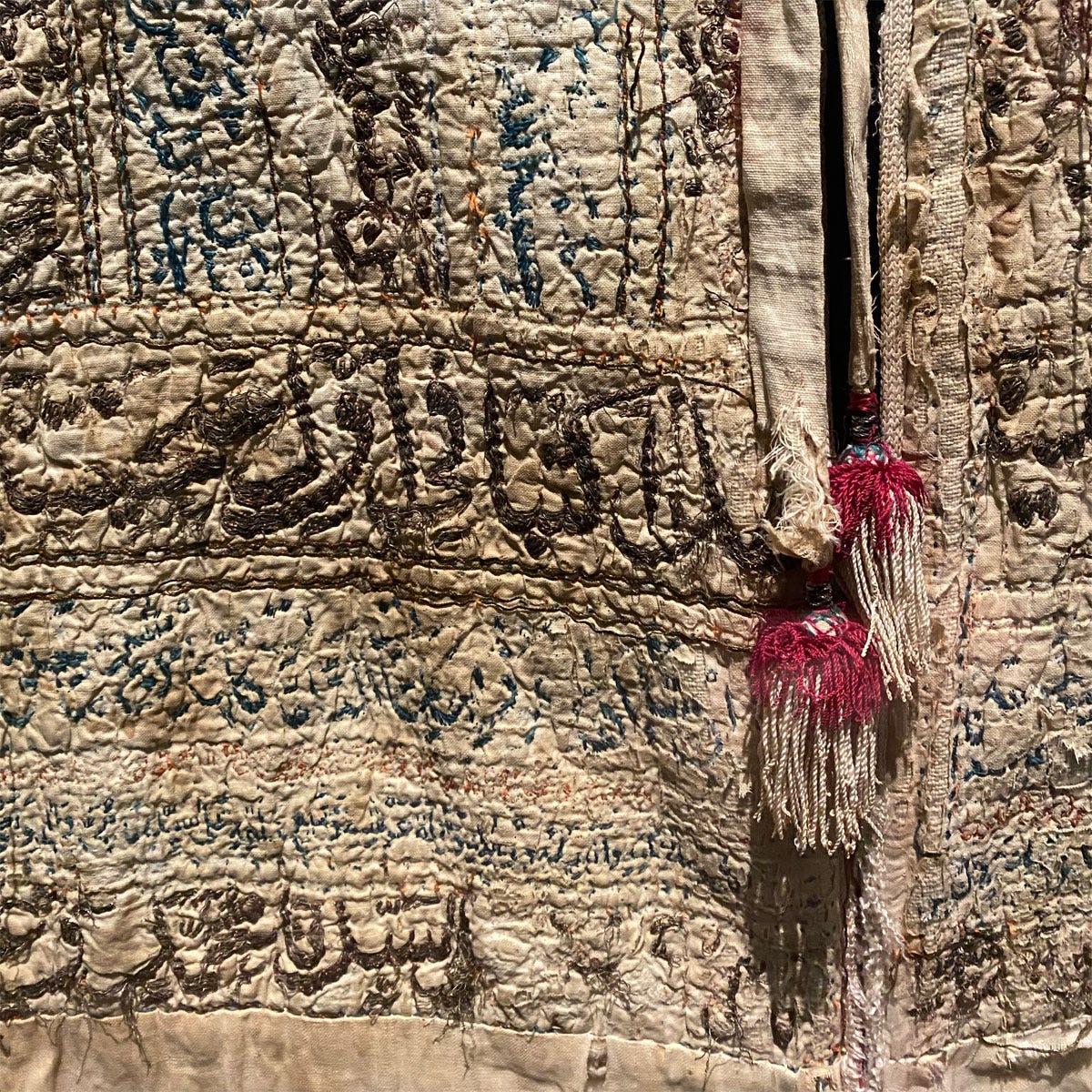

Suzani: The most important piece of embroidery in Uzbekistan since the 17th century, the suzani is a large piece of fabric embroidered with silk thread. This type of craft was reserved to women, who handed down their know-how from one generation to the next. Suzani were part of a woman’s dowry, and were originally used as a bed cover but eventually also became a luxury wall decoration. A suzani can take anything between one and eight years of work, and is generally based on one of two themes: flowers or stars.

The technique best known as ikat from Indonesia, was developed in Uzbekistan as abrbandi. It’s a resist dyeing technique that consists in tying yarn in specific ways before dyeing, sometimes going through multiple colours with different bindings, so that the pattern appears once woven as if of its own accord. While ikat dyes both the warp and weft threads, in abrbandi only the warp threads are dyed.

The Qaraqalpaq (to use their endonym) are a Turkic people who, in the period of the Bukhara Emirate, were semi-nomadic and notable for the elaborate and highly coded textiles and jewellery which marked the different stages of a woman’s life.

Tobelik: Diadem worn by Qaraqalpaq women of marrying age, replicating the helmet of legendary women warriors. Only two have been preserved.

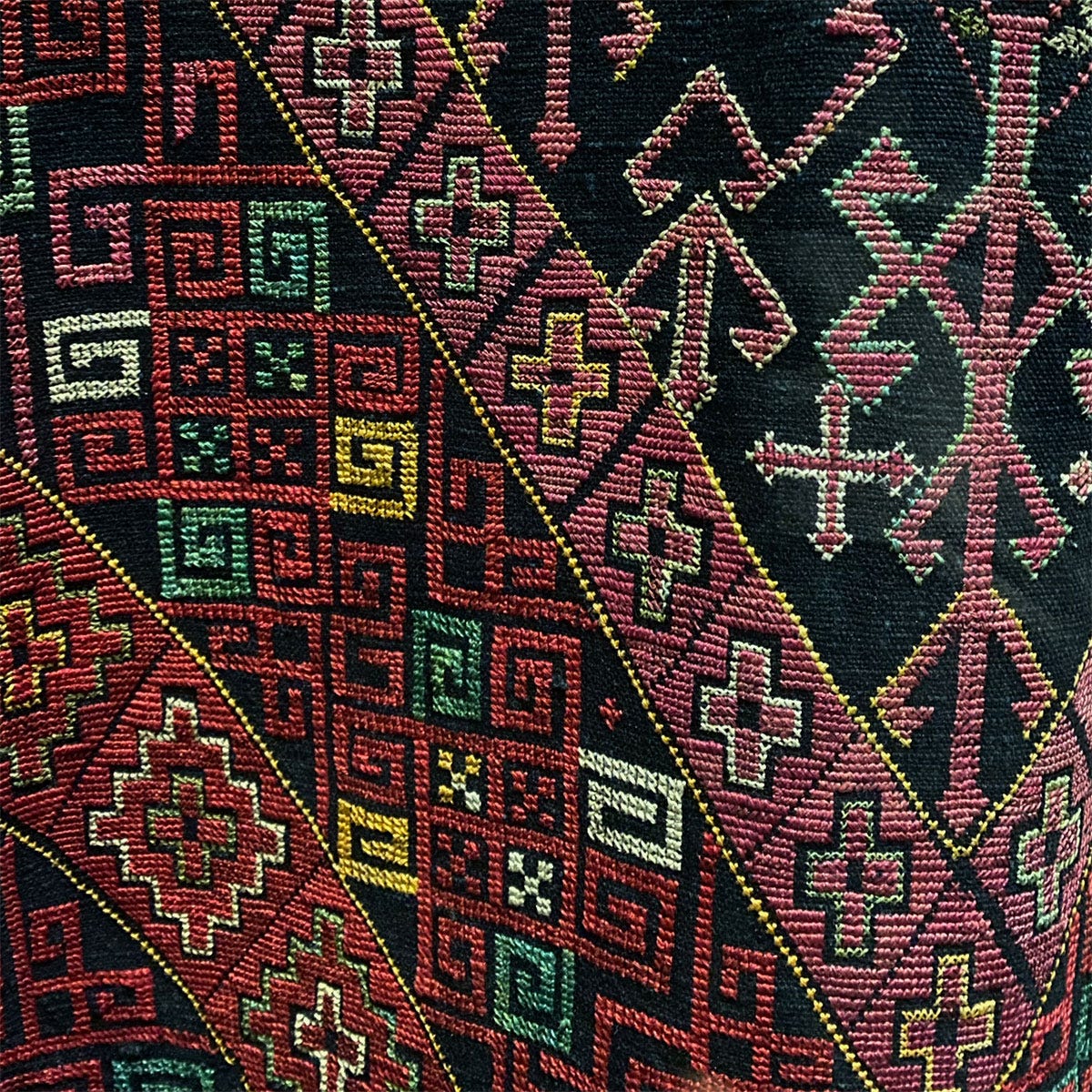

Ko’k ko’ylak4: Ceremonial gown worn by Qaraqalpaq women from wealthy families on their wedding day, characterised by rich geometric patterns cross-stitched on the front of the gown and the edges of the sleeves.

Kiymeshek: A woman’s tailored head veil, which covers the hair and shoulders but leaves the face exposed. It’s basically the same as a khimar, except the kiymeshek is extravagantly decorated with embroidery

Takyaduzi: A woman’s wedding headdress, composed of innumerable metal pieces that rustle as she moves, keeping evil spirits at bay.

Paranja: A long robe traditionally worn in public by women in Central Asia from the age of ten. A type of burqa, it covers the head and body and is completed by a horsehair face veil to ensure anonymity. The qaraqalpaq variant was called jegde and left the face uncovered – with the option for the woman to pull the side of the cloak across her face to hide it from onlookers. After the arrival of the Russians in 1868, paranjas became brightly colourful and ornately embroidered, until they were banned by the Soviets in 1927.

For the sake of fairness, here are the events that led to the invasion, from the Wikipedia article:

“In 1218, a small contingent of Mongols crossed borders in pursuit of an escaped enemy general. Upon successfully retrieving him, Genghis Khan made contact with the Shah. Genghis was looking to open trade relations, but having heard exaggerated reports of the Mongols, the Shah believed this gesture was only a ploy to invade Khwarazm.

Genghis sent emissaries to Khwarazm to emphasize his hope for a trade road. Muhammad II, in turn, had one of his governors openly accuse the party of spying, seizing their rich goods and arresting the party.

Trying to maintain diplomacy, Genghis sent an envoy of three men to the shah, to give him a chance to disclaim all knowledge of the governor's actions and hand him over to the Mongols for punishment. The shah executed the envoy… and then immediately had the Mongol merchant party (Muslim and Mongol alike) put to death and their goods seized. These events led Genghis to retaliate with a force of 100,000 to 150,000 men that crossed the Jaxartes in 1219 and sacked the cities of Samarqand, Bukhara, Otrar and others. Muhammad's capital city, Gurganj, followed soon after. The Shah Muhammad II of Khwarazm fled and died some weeks later on an island in the Caspian Sea.”

Abruptly ended, like so many beautiful things, by a Bolshevik takeover shortly before it was absorbed into the Soviet Union.

More prosaically, the fear was that trade secrets could not be kept when a woman moved from one family to the other upon marrying. Today however, the art of zardozi continues, with women among the practitioners.

Here’s a page with quite a lot more detail about this garment on qaraqalpak.com.

Thank you so much, as ever your post in both interesting and informative, and the pictures are gorgeous.

Well, that was an excellent way to start a Spring day! Thank you for this window into a little appreciated (at least in the US) yet very important region.