In another installment of blindly stumbling into situations that turn out years later to be of significant interest: in 2006, I was backpacking in the Madagascar highlands (as you do) and somehow signed up for a hike into Zafimaniry country.

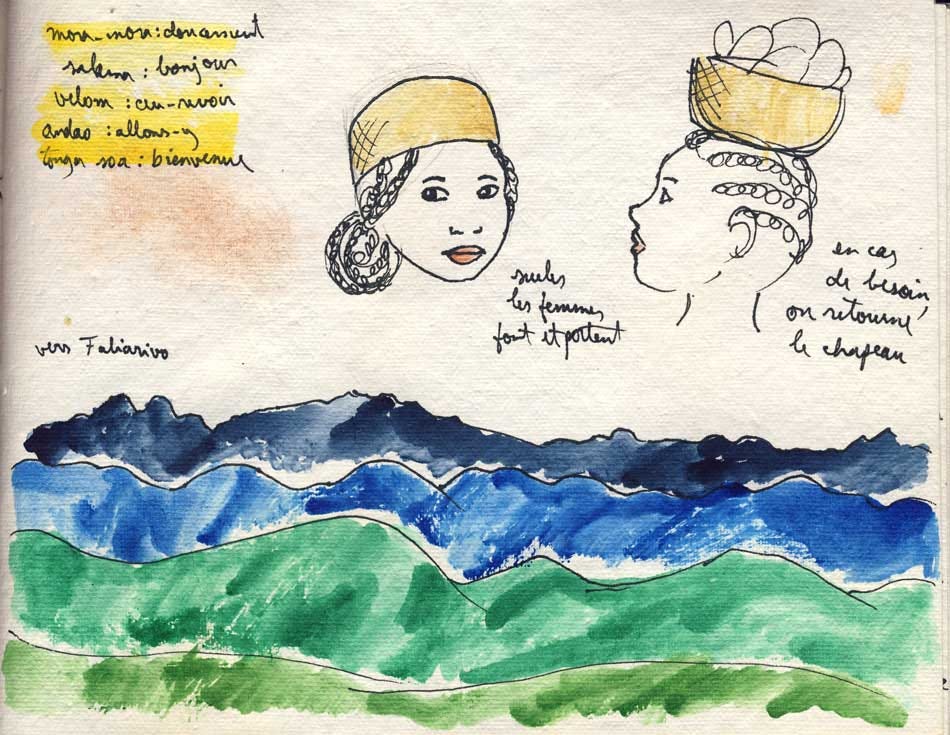

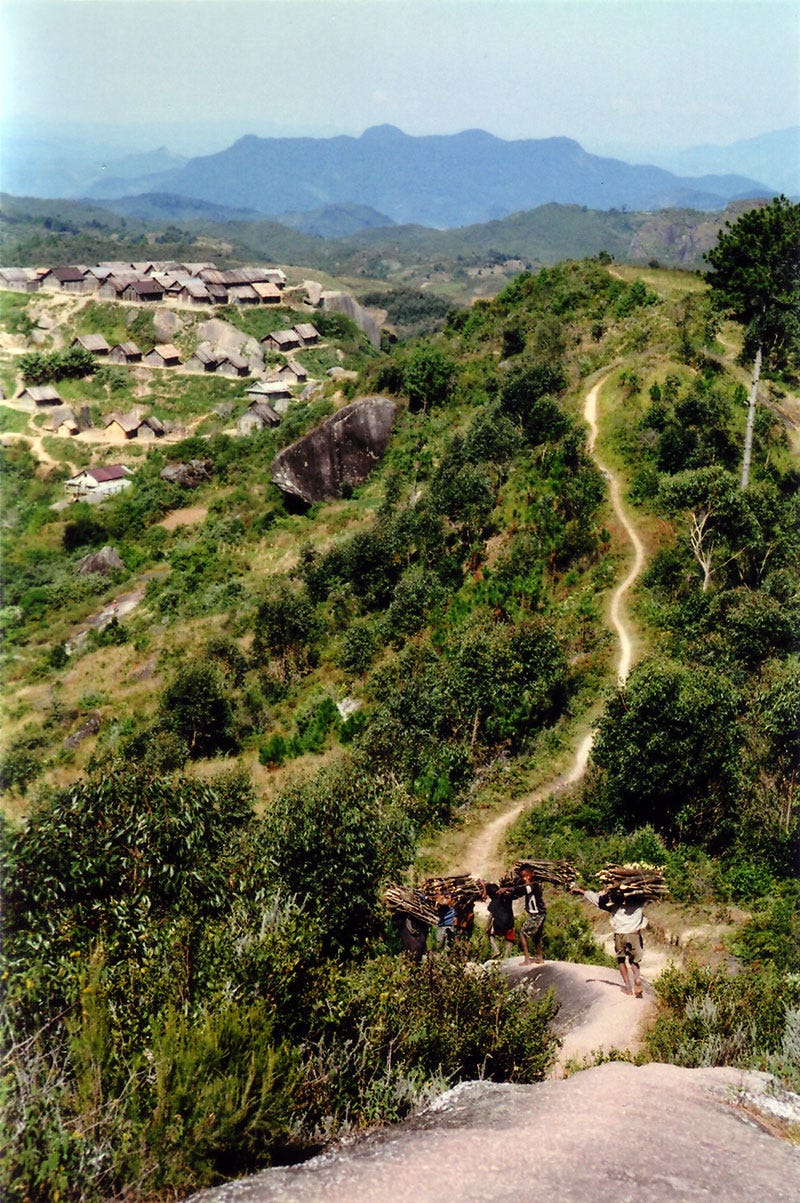

The Zafimaniry (zah-fee-mah-NEER1) are quite a small ethnic group of no more than 25,000 members today, largely isolated since they settled in this part of the Red Isle and only marginally more reachable today. Only one village, Antoetra, is accessible by road, and as such has become the “capital” of the other 60, a sort of shop window for the whole2. The rest of this small country is only accessible on foot. We – a French couple, our guide Landry, and myself – were heading to a village called Faliarivo, a hilly three hour hike each way. But what a hike… 3

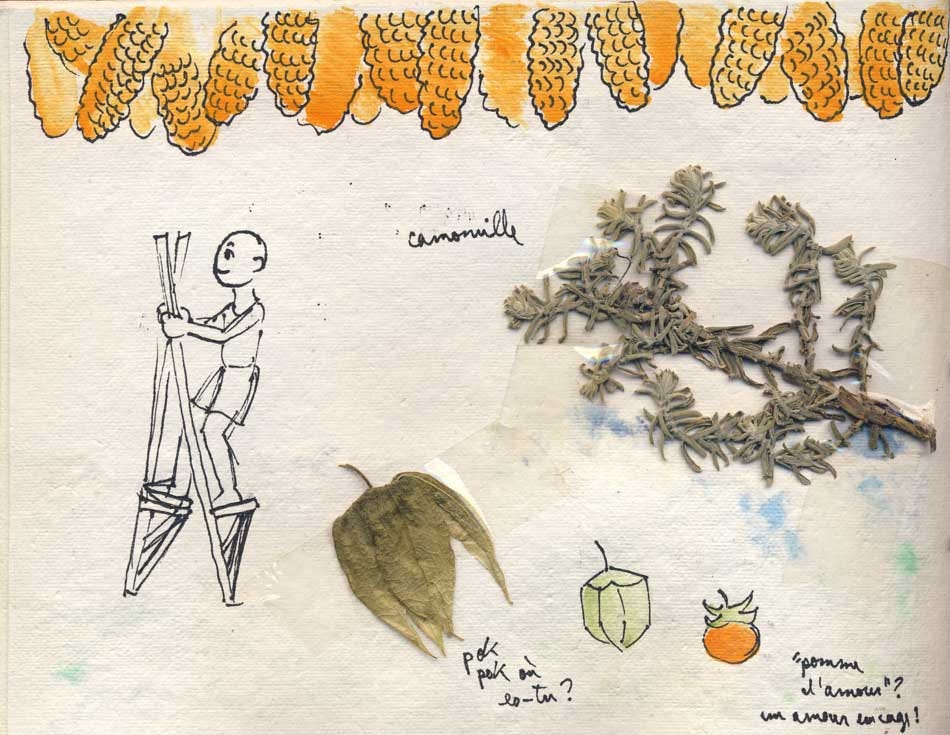

My travel journal, the brevity of which I now regret, describes “silver ferns, aloe, streams running through red earth beds, camomile everywhere…”

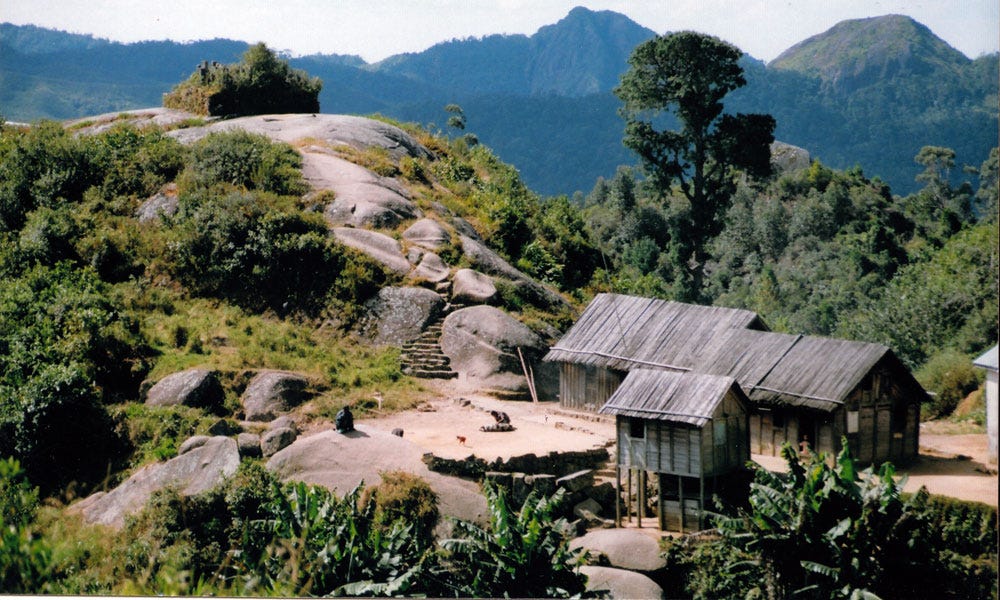

Upon arrival, custom and courtesy dictated we start by visiting the village elder – whose house is marked with a sculpted bird – to ask for his permission to visit.

After a chat with the 90-year-old, around whom all the village children had clustered for the occasion, it was time to enjoy the sights around the village.

Whereas their Betsileo neighbour build distinctive mud huts, the Zafimaniry are known for their woodwork, notably their strong wooden houses put together solely with a system of mortice and tenon joint. When construction is complete and the house has achieved a quality of durability and hardness (teza), this completion is marked by carving the wooden window shutters (hoaka) with geometric designs. This type of decorative engraving is called sokitra – and is what has brought attention, for good or bad, to the Zafimaniry.

If you search online for info on Zafimaniry woodcarving, you will find this statement paraphrased on pretty much every single website that mentions the craft: “There are no less than 21 motifs. The spider’s web pattern (tanamparoratra) stands for family ties, while the honeycomb (papintantely) represents community life.”

Strange that of the 21 supposed motifs, only these two are ever explicitly named! It’s as if every one of these websites plagiarised the same source. (Spoiler: this source, which as we’ll see below is misleading4.)

When such a claim is parroted around the web with no deeper level of detail to be found, and no source provided, my BS sensors starts tingling. I kept digging till an exceptionally clear-sighted paper by Taku Iida, from the National Museum of Ethnology in Japan, confirmed there was a problem. It’s worth sharing this long passage in full, with the italics being my own emphasis:

As discussed previously, Zafimaniry patterns on window shutters and other items were not intended to possess special meanings. However, it was observed that people visiting from outside the community were keen to derive symbolism from these designs. Consequently, local Zafimaniry guides began to provide commentaries surrounding the origin and meaning of these patterns to satisfy the curiosity of outsiders. It seems that international organizations, such as the Madagascar branch of UNESCO, have authorized these accounts by publishing a chart of these commentaries in an official booklet, largely based on oral descriptions provided by local guides. Some Antoetra people, however, report that nearly all this information was derived from a single skilled carpenter in the village of Sakaivo who passed away in 2013. It is not possible to ascertain whether the information provided by local guides is false. However, the primary concern is that if such knowledge is made too readily available, the intrinsic value of intangible heritage may be adversely impacted. Moreover, to preserve the integrity of knowledge relating to these practices, such information should be transmitted orally within the community, and not through a printed publication. The appearance of the UNESCO booklet, therefore, although having sought to preserve an intangible heritage, may ironically threaten its survival by trying to concretize knowledge that is inherently changeable and evolving, a characteristic that forms an essential part of its core value.5

So the sokitra "symbolism", now touted around the web, was made up in response to tourist pressure (by a single person, in the most tourist-impacted village), and UNESCO made the unfortunate gaffe of setting it in stone by publishing it. It’s true that the makers have names for the various shapes they use – you have to be able to refer to designs one way or the other – and these names are based on familiar objects or sights. But they are just convenient labels that are known to change from village to village, and the imposition of meaning upon them is a typical Western thing to do. The obsession with symbols, with what things mean, can only come from a culture so lost in its own head and so divorced from original creative practice that it’s no longer possible for anything to just be what it is; it must at any cost point to something beyond it that is abstract. Abstract is understood without question to be “higher” and “more evolved”, because to remain on the level of form and material without clothing it in pseudo-intellectualism is “primitive” (that is the mindset, but most definitely not mine). It’s a mindest so deeply ingrained in western societies, and so unquestioned, that even the most well-meaning tourist (that rare beast) pushes it relentlessly at locals: to elevate a native art form to a level where they can respect it (and with no awareness that this is what they’re doing), they must force it into the only standards they know—their own Western outlook.6

I have more thoughts than I can put into words about how insidious and damaging this complete lack of self-awareness is and has been to native cultures. What’s been happenign in these highlands is a real-time example of how it can contaminate and forcefully rewrite native art forms. Of course a Zafimaniry tour guide is going to make up stories for tourists, since they want to hear them so badly. But as the craft itself is increasingly catering to tourists for its survival, the stories are increasingly reshaping the craft and replacing a more profound reality, which is this:

Creativity is a living force that flows through the maker and expresses itself in beauty that does not need to justify itself. But in the Rationalism-drenched world there is a deep conditioning to the effect that everything must be explained, that beauty has no intrinsic value unless it can be intellectualised, that creatives need to pin down their work like butterflies on a board to provide a straightforward “this symbolises that” equation their intellectual superiors can grasp. But this is a lie. That’s not how reality works, let alone the vaster reality creatives dwell in. You can fill a bucket to have a neatly defined portion of seawater to scrutinise, but only a fool would think this is a satisfying summation of the ocean.

This is the West feeling keenly the self-inflicted loss of its own native crafts7 , but instead of returning to its own roots, the West is taking hold of other cultures’ creative traditions and dragging them down the same narrow-minded drain. To remove the centre of craft from the hand and senses to thinking and fantasy is to steal it from the everyday person and remove it to an “elite” specially trained to understand and interpret it. This process spells death for an art tradition; it may go on forever like a zombie, but its inner heart is lost. Imagination is replaced by formulation.

Anyway, back to the Zafimaniry. I was disturbed enough to get a copy of À Madagascar, chez les Zafimaniry, which is an informal account of the first ever ethnographic mission to these villages, by Jean-Pierre Hammer, followed by the very first study of sokitra, by Pierre Vérin. Both accounts were written in 1964, long before the first tourists, and before outside demand turned sokitra into a commercial venture. When asked about the significance of the motifs, sixty years ago, the Zafimaniry response was simply: “It’s done this way because it’s beautiful and because that’s the way the Ancestors did it.”

As simple as that.

Vérin then astutely suggests: “[T]he Zafimaniry artist offers us motifs immersed in a whole that has not been upset by acculturation, and of which it may be time to determine structural explanations by going back to the level of the unconscious of individuals.”8

The unconscious: that very ocean in which creatives swim, while others watch from the safe dry shore of reason, making stuff up to pretend it can be contained in mental constructs.

After such a post, I feel we can’t leave Madagascar without a couple of animal encounters…

The last syllable is usually silent:

Fianarantsoa: fyah-nah-ran-TSO

Faliarivo: fah-lyah-REEV

Ambositra: ahm-BOOSTr

In a very real way, because that’s where tourists and buyers of Zafimaniry crafts stop. When we returned from our long hike, we were taken from house to house to shop. But we were also served coffee by Landry’s parents as we rested, a thick black liquid sweetened with eucalyptus honey gathered for us. And that was the first time I ever had coffee, under eaves of drying maize.

The beauty of the landscape does conceal an alarming fact: this area, as far as the eye could see, was covered in forest when the Zafimaniry settled here in the 18th century. They have relentlessy deforested it through slash-and-burn agriculture (tavy).

In this quote from Unesco Intangible World Heritage, the only statement that is based in fact rather than fancy is that no two pieces are identical: “The geometric patterns are highly codified and reflect not only the community’s austronesian origins but also the Arab influences in Malagasy culture. Although the number of motifs is limited, the creativity of the craftworkers means that no two pieces are identical. These motifs carry rich symbolic significance related to Zafimaniry beliefs and values. For example, the tanamparoratra (spider’s web) symbolizes family ties, while the papintantely (honeycomb) represents community life.”

There is a strong parallel with people who say “I don’t see colour”, which sounds decent until you realise the real meaning here is “I pretend everybody is white”.

“[L]’artiste zafimaniry nous propose des motifs immergés dans un complexe que l’acculturation n’a pas encore bouleversé et dont il est peut-être temps de déterminer les explications structurales en remontant jusqu’au niveau de l’inconscient des individus.”

Thank you so much for this post. Speaking as an artist, this is by far the most powerful, profound, and insightful thing I've ever seen written about art.

Thank you for sharing. Beautifully understood and articulated.