This post has ended up shorter than I intended, as I started work on it while juggling a move to Oxford for the rest of the year. I’m here on a Visiting Research Fellowship in Creative Arts at Merton College and since I arrived, I have been swallowed up by this wonderful place and struggling to take my mind off the work I’m doing here. So I decided to send this a bit truncated rather than delay any longer.

By “lost dyes” I don’t mean dyestuffs that are forgotten or that we no longer know how to use. Such spurious claims are made with absurd regularity for Tyrian purple and have been made for folium, both of which were as “lost” as the Americas were when a confused Columbus finally turned up. My reference is instead to the fact that in the early twentieth century, synthetic dyes spread to the Middle East and quickly wiped out the use of local, traditional dyes at a time when these were not necessarily documented in writing.

My interest in traditional embroidery was already awakened before the exhibit Material Power: Palestinian Embroidery, and culminated in my recent artwork, Resilience, for which I dyed the silk thread specially. I used madder, which I know to have been historically used in the region, but this got me interested in trying to reconstruct the historical palette of tatreez, the way I have been doing with inks.

I’m using “historical” rather than “traditional” because for the past hundred years or so, the tradition has embraced DMC cotton perlé as its new source of colour, and become strongly codified in terms of the brand’s colourways: up until the Nakba, different areas of Palestine each had their own specific palette.1

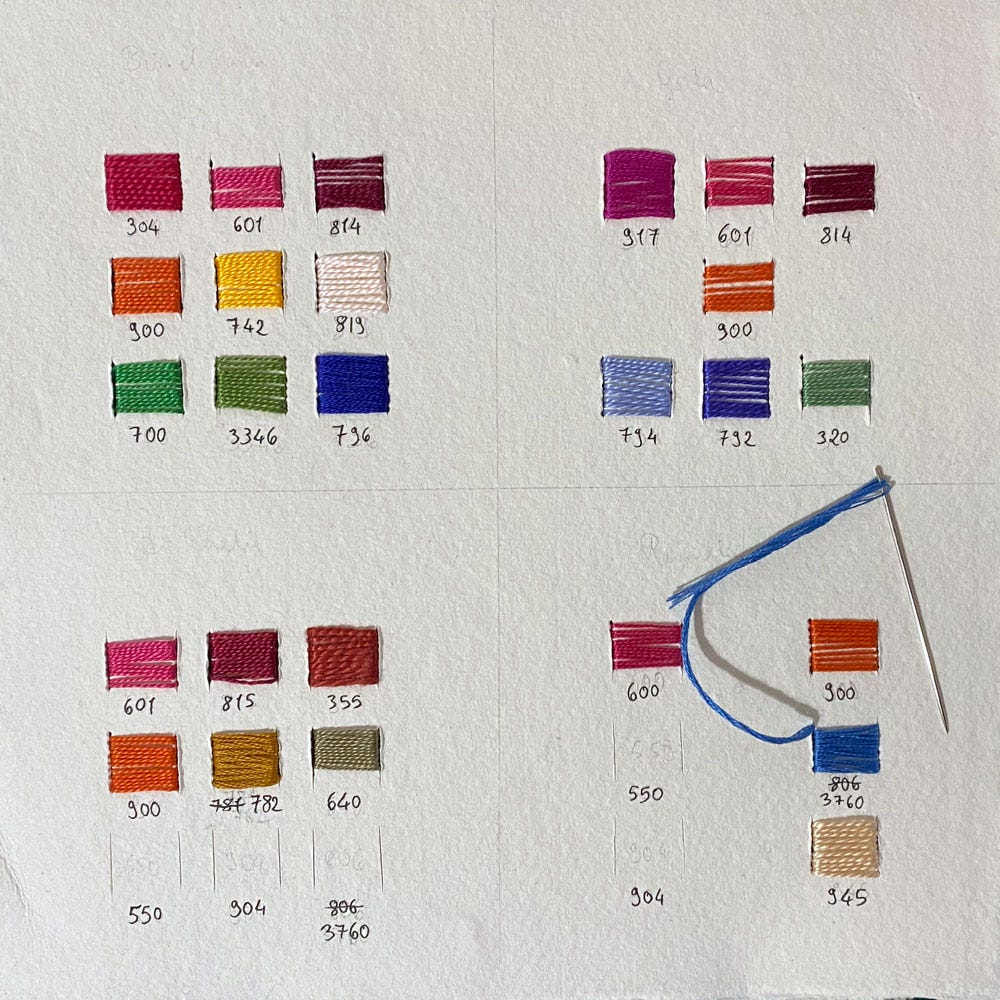

In order to properly visualise the palettes used today, I’m making a sampler; it’s not yet complete but give you a general idea2.

I don’t (yet) have a complete historical palette to contrast this with, but this would be the kind of colours you would see in it:

The way the availability of a wider and perfectly predictable palette has allowed for such a specific expression of identity through colour, taking the tradition into new dimensions, is fascinating in its own right, but I’m interested in the colours that came before western imports, the tail end of a long history of natural dyes in the region.

It’s easy to tell natural from industrial dye when looking closely, but it’s less easy to tell what the threads were dyed with. My investigation, which is ongoing, consists in looking for text sources and experimenting. I don’t expect to arrive at a final truth in the matter, because there are more than one way of achieving most colours and different town dyers probably each had their preferred method—hardly any of which ended up written down. What I’m hoping to arrive at is to recreate the thread colours seen on historical dresses, using nothing but the dyestuffs that would have been current in that place and time.

Text sources

What do we know about pre-DMC embroidery?

Historically, all embroidery was done with silk floss (which is barely spun silk) dyed in Syria with natural dyes3. Synthetic dyes referred to as aniline, by-products of coal tar processing, were developed in Germany from the 1880s and widely adopted in Syria after the First World War, replacing historical dyes. So there was a short period of time during which aniline-dyed silk thread was sourced from Syria, but the 1930’s saw the arrival of perlé cotton, which gradually replaced silk altogether as it offered a similar lustre at a much lower price. There’s no clear cut-off date, but dresses predating World War 1 are almost certain to display historical dyes, and from the 1930s onwards are most likely to feature imported perlé. For text sources that might have recorded historical dyeing processes before they vanished, we need to look at the early twentieth century or earlier, but such sources are sadly sparse.

Shelagh Weir’s wonderful4 book Palestinian Costume put me on the track of only two authors that took the trouble of looking closely at dye plants.

From Cedar to Hyssop, 1932, was written by Grace Mary Crowfoot, British textile archaeologist, in collaboration with Louise Baldensperger, who spent her life between Jerusalem and Artas. In an all-too-short chapter on dyes, the book mentions the obvious madder and indigo before going on:

The leaves of the almond tree are said to give a yellow, and pomegranate bark with iron, a black; the safflower, is only used to colour rice, its use as a dye plant does not appear to be known. We have only heard of a green once—at Jerash, in Trans Jordan, it is obtained by the use of an umbelliferous plant Ridolfia segetum [بسباس] and indigo.

By that time, this was already synthetic indigo, and “All other dyes used there for dyeing the wool brought in by the Beduin were anilines, so far as could be ascertained.” A note on the green mentioned here: there is no natural dye that yields a good green directly, and this colour is almost always created by first dyeing with yellow, then overdyeing with blue (typically indigo). There are many, many sources of good or decent yellow in the plant world, and I believe the use of false fennel recorded here is a matter of it being locally abundant, rather than it being a dye plant of special note.

The second source was Gustav Dalman’s Arbeit une Sitte un Palästina, 1937 (vol. 5) and is the most detailed I have been able to find so far. The author lists dye plants documented to grow in Palestine, that could have been used, and then lists dyes that were definitely used. Here’s this passage, translated from German5:

I am indebted to Mr. John Dinsmore, Jerusalem, for the following information on dyes used in Palestine:

For black, blue and grey, American logwood (Haematoxylum campechianum) is used,

For black and light brown, Palestinian* pomegranate peel (Punica Granatum رمّان)

For black, Egyptian senna leaves (Acacia nilotica سنط) and Egyptian lebbek leaves and pods (Albizzia lebbek لِبَخ), Syrian-Palestinian oak galls from the gall oak (Quercus lusitanica معفاص).†

For blue, Palestinian indigo (Indigofera argentea نيله) is the usual color,

For red-brown, Palestinian onion skins (Allium cepa, ar. بصل),

For brown, branched asphodel (Asphodelus microcarpus [now ramosus], ar. بصل عنصل),

For light red (crimson) cochineal from the cochineal insect on the Brazilian cochineal cactus (Opuntia cochenillifera صَبر), which is also grown at Nablus,

Red from the Palestinian madder root (Rubia tinctorum فوّة), and from the kermes insect on the Palestinian evergreen oak (Quercus coccifera, ar. بلّوط),

Dark red from the stems and leaves of the Palestinian corn (Zea mays ذُرة صفرا). ‡

Green or yellow-green comes from the tamarisk (Tamarix طرفاء),

Yellow-green from the Yellow broomrape (Orobanche lutea بَرنوق),

Orange-yellow from the Palestinian safflower § (Carthamus tinctorius عصفر).

Yellow comes especially from the berries of a type of buckthorn (Rhamnus petiolaris) and from weld (Reseda luteola, بَليحاء).

Notes on the above:

* “Palestinian pomegranate”, “Palestinian indigo” etc don’t mean to imply discrete local species but simply indicate these are locally grown.

† These are also used to make black ink, but in both cases the author omitted to mention that some form of iron salt is essential to cause the reaction that creates black.

‡ Now that is intriguing! Some varieties of maize are rich in anthocyanins, for instance purple corn, which I have tested for my book Wild Inks & Paints. It’s so intensely pigmented that it produces nearly black purple, but it’s conceivable that dark purplish reds could be obtained by dyeing with it, and I intend to test it. But I had no idea such varieties ever existed in the Middle East, where nowadays only the most generic kind is known.

§ This contradicts the earlier text, but this kind of variation is to be expected from place to place, even in a relatively small country.

One more thing to note from this excellent list is that there is no mention at all of overdyeing, which was described above. We should take this therefore as a list of confirmed dye plants, but not as an attempt to describe dyeing practices.

Material sources

Let’s look at dresses themselves and see what can be observed to match or complement the descriptions above. To do this from photos is less than ideal but with a limited list and some experience, not impossible

This embroidered panel is heavily faded from daily outside wear, but the manner of fading provides instant information: most of what is now quite a pale reddish-brown can only have been madder red, while the parts that are now light magenta indicate cochineal.

Below is a detail of a photo from Shelagh Weir’s book. At full intensity, the two reds are quite close but you can just see the magenta dominant in one (see the solid vertical band towards the right of the image) contrasting with the orange dominant in the other (see the red in the flowers).

Other observations we can make here is that we have two shades of yellow: one light and bright, the other slightly brown in comparison. It’s possible that this browner yellow comes from pomegranate while the clear one is from weld, as I have obtained similar results, but these are not the only possibilities—as I mentioned earlier, yellows are rife anywhere you go. However, since we also find black here, pomegranate is a strong contender as there would have been no need to use an extra dye bath: just soak pomegranate-dyed thread in an iron mordant bath to turn it black.

Finally, indigo is visible in the beautiful blue of those two squares, and also in the green: while this looks like a solid colour in the embroidery body, look at the fringe on the right: the overdyeing of yellow and blue to make green is very easy to observe here.

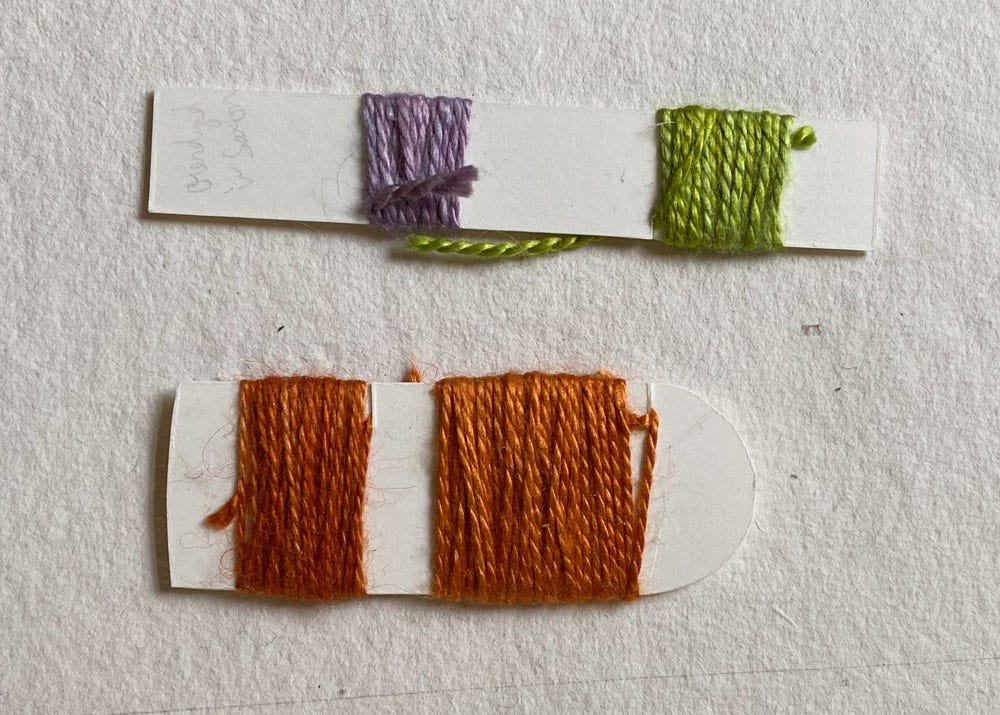

I have just begun to try and reproduce historical tatreez hues, and below are preliminary attempts: orange obtained from madder at the bottom, and two hues resulting from overdyeing (weld + indigo for green, cochineal + indigo for purple6)

This is where I need to cut off for now, though this is a topic I plan on returning to in future, with more results to share. Heavenly Figures will resume next time, and during my stay here expect more along those lines as I’m diving more deeply into calendars and ways of measuring time…

These palettes, requiring exact DMC colourway numbers, are still in use in the diaspora by the descendants of the displaced, keeping the connection to their lost home.

More complete, albeit digital visualisations of the best established palettes can be viewed on Tatreez Traditions.

Except for some Beduin embroidery, as nomadic tribes would collect and spin the wool from their flock and either dye it with the means available to them, or bring it into the nearest town to be dyed.

And affordable: if reading it online at the Internet Archive doesn’t appeal, try eBay.

I don’t speak German! Google translate did the bulk of the work but I checked and corrected/updated the species names individually, and substituted Arabic for his phonetic transcriptions. I also bolded the colour names and reformatted the original paragraph for more clarity.

For a quick preview I used Saxon blue, which is an indigo-derived dye that you only have to dissolve in hot water to use. It produces nowhere near the deep and magical hues of indigo, but it was a helpful quick natural blue just to get a sense of the results. Unlike most dyes, which I can get started on the side and stick in the fridge to finish up later, it takes a lot of planning to start an indigo vat and it doesn’t really keep, so all the material needs to be ready beforehand.

Having lived in the American Southwest from r a long time, I’ve paid close attention to the mix and transfer of food crops between the old world and the new. The Navajo and Puebloan weaving cultures (I think mostly post-Spanish contact, because the Spanish brought sheep) use natural dyes including cochineal. Was there a pre-contact cochineal in Palestine? Or was it brought over from the Americas?

I think it is so important to keep culture alive through traditional foods, and traditional crafts. When things are talked about, passed down, even orally they will always stay alive and no amount of history erasing will bury the culture. This information is a delight to read Joumana!