No, this has not suddenly turned into a parenting newsletter…

You’ll have noticed by now that I have a thing about looking closely at details that tend to get lost in the whole. One type of such details is diapering: patterns applied to an otherwise flat surface. These exist across cultures and disciplines (architecture, textiles, stained glass) and the term was first brough to my attention while taking a gilding class with Helen White, whose own work is an exquisite interplay of gold and patterns inspired by Christian art.

Since then, I’ve had an eye out for diapers in manuscripts from the Islamic world, where flat areas of colour are filled with freehand geometric or biomorphic patterns in a repertoire that appears to be each artist’s own.

The Arabic term for it seems to be mudamshaq مُدَمشَق (“damasked”); this really refers to rich patterned fabrics, as does the English word originally. But I really don’t know if that word, or any other, was specifically used by the muṣawwir when he set out to fill areas of flat colour with an enlivening pattern.

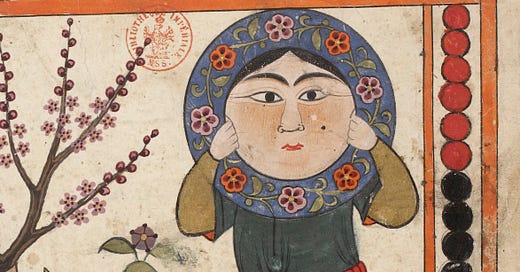

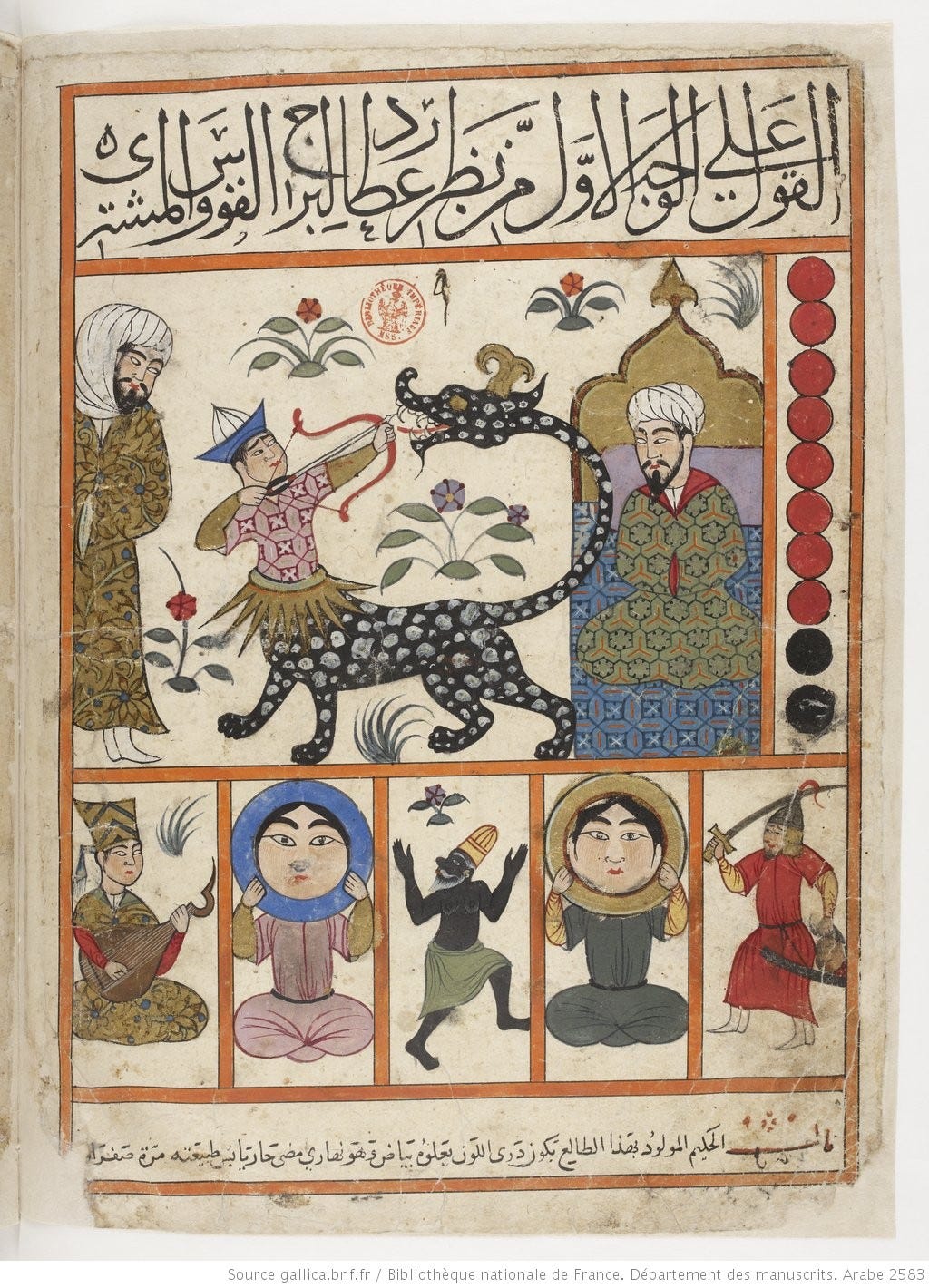

In this introduction I’m surveying the patterns from a single manuscript, the astrological treatise Kitāb al-Mawalīd (“Treatise of Nativities”), attributed to Abu Ma’shar al-Balhi and illustrated by Ali Qanbaz from Shiraz1, no later than the early 14th century2. The manuscript is also of interest for its delightful astrological iconography, which is a topic I’ll return to zoom in on in the future.

For now, I’ll focus on the diapers: the repertoire of patterns in Kitāb al-Mawalīd is quite small3, and mostly made up of clever variants on exactly two basic grids. But playing with colours and occasionally adding or removing a small detail ensure they never look repetitive. (As a bonus for paid subscribers, and though I don’t know how many of you may have a use for them, I will be sending a follow-up post with a selection of hi-res patterns from this source, to use any way you fancy.)

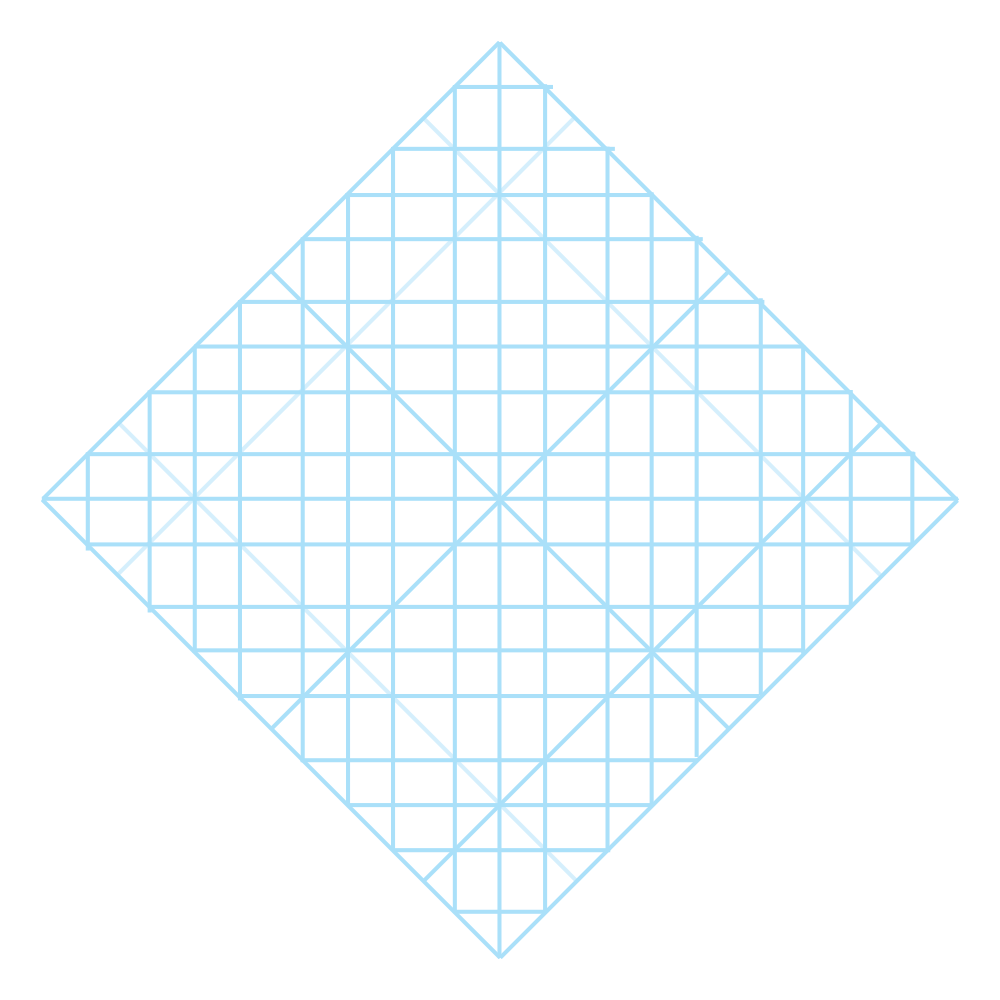

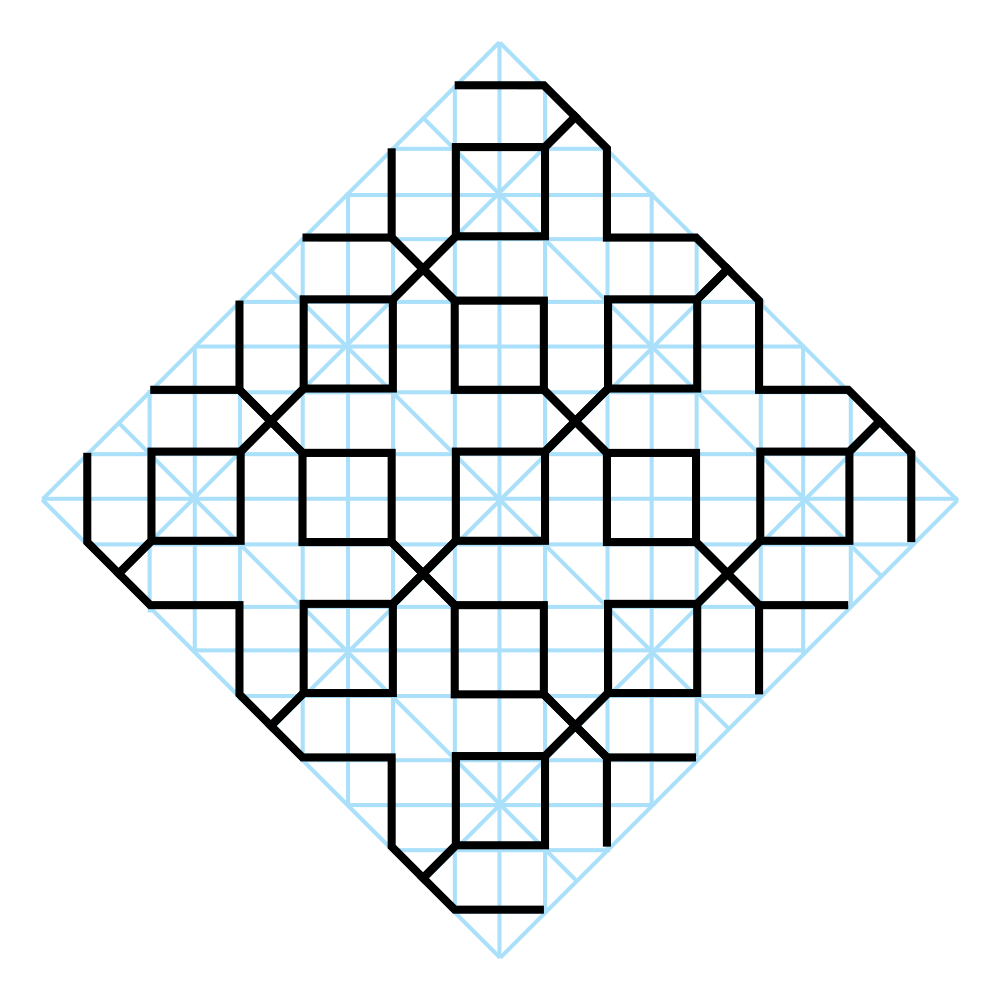

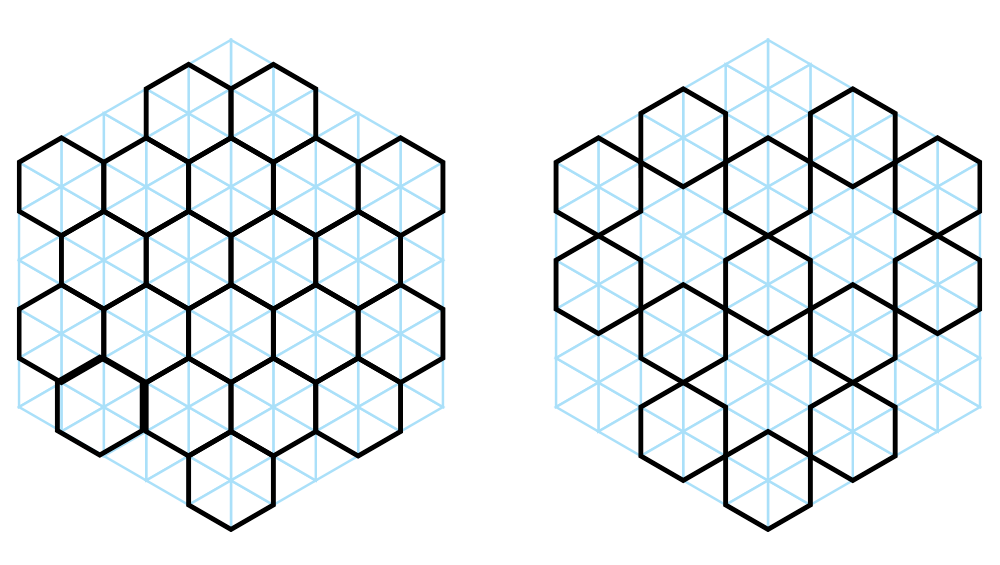

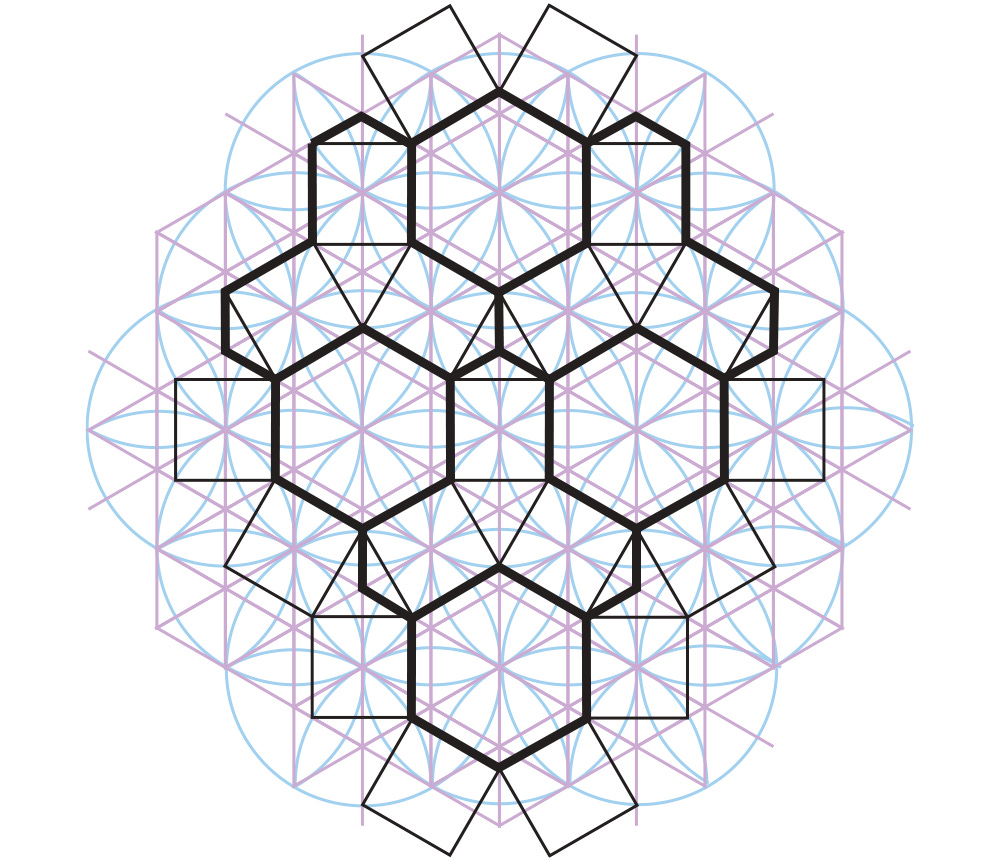

The first of the two grids is a well-known derivation from a grid of squares. I’m quite sure the muṣawwir did not go through the process of building it4, instead drawing the finished patterns freehand out of long habit (they’re easy on a small scale), but this is what it looks like:

The pattern seen on the characters below is created from this grid by joining the dots in the manner showed underneath.

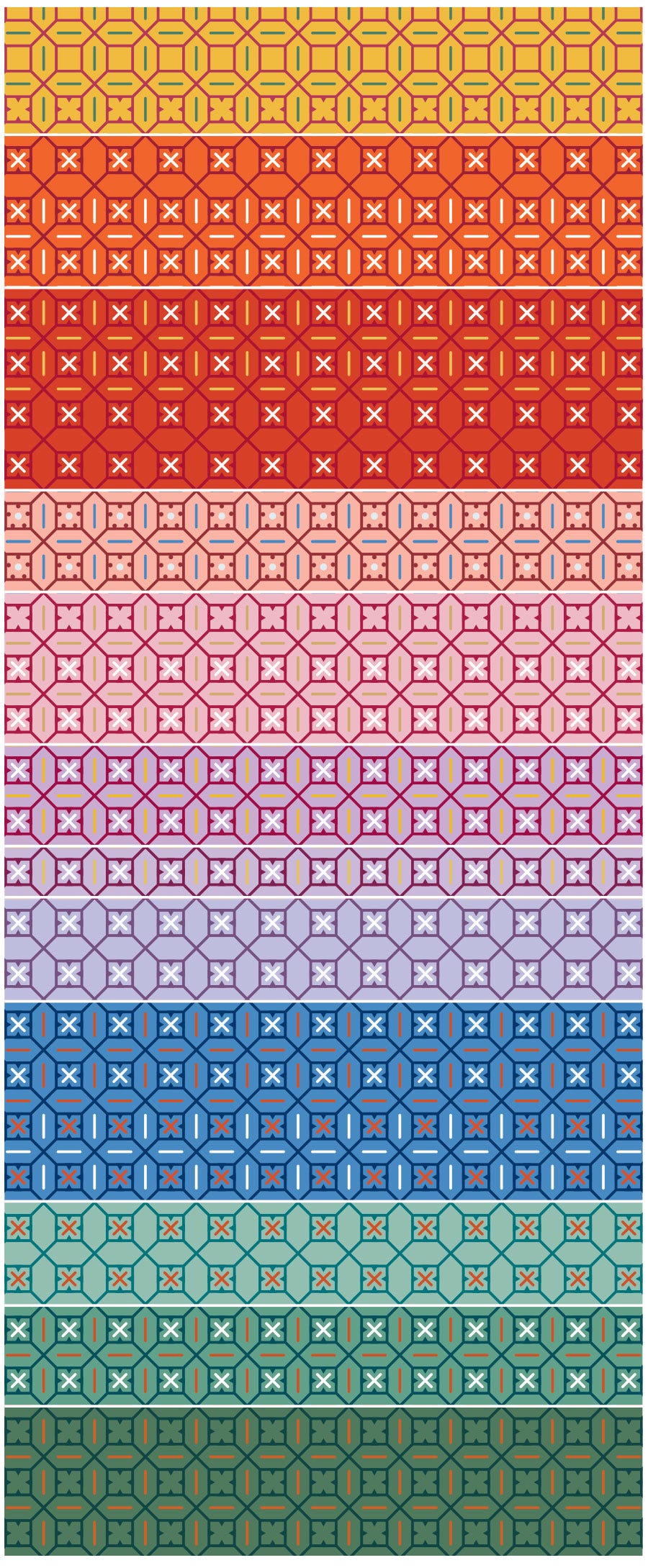

Below is every iteration of this pattern used in the manuscript!

The second square-base pattern, as seen on the right-hand characters in the two images below, is the same minus a few lines to allow every four lozenges to join into a cross.

And here are all its variants…

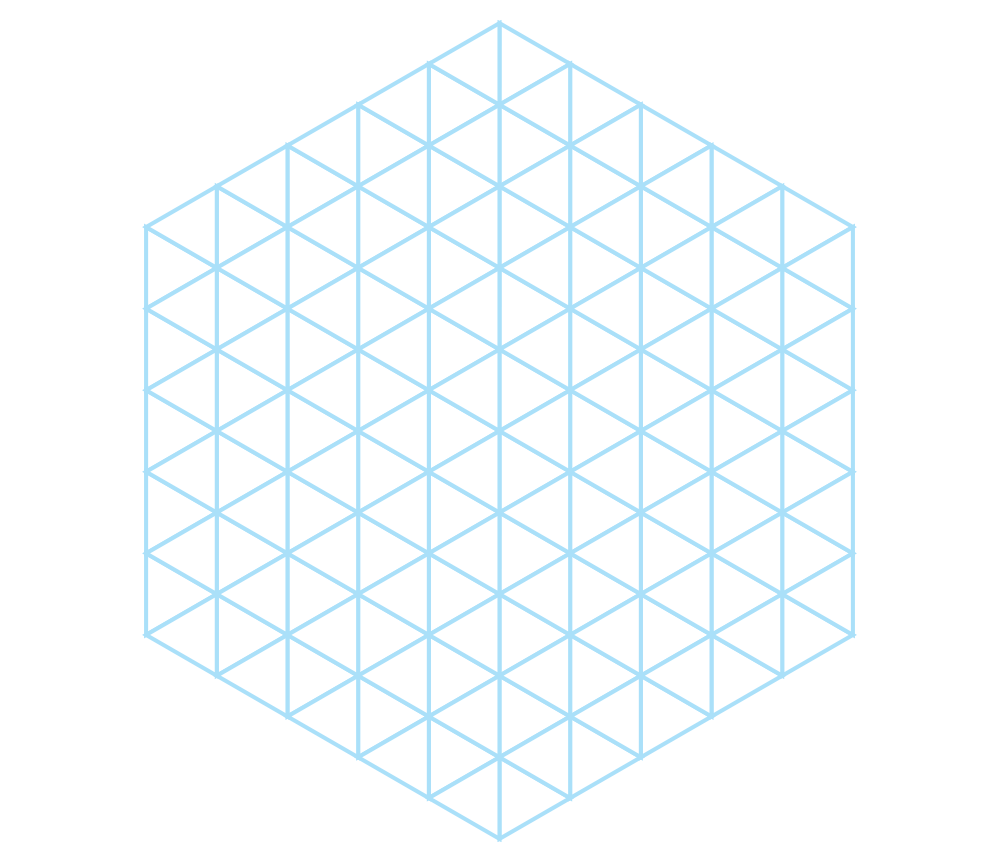

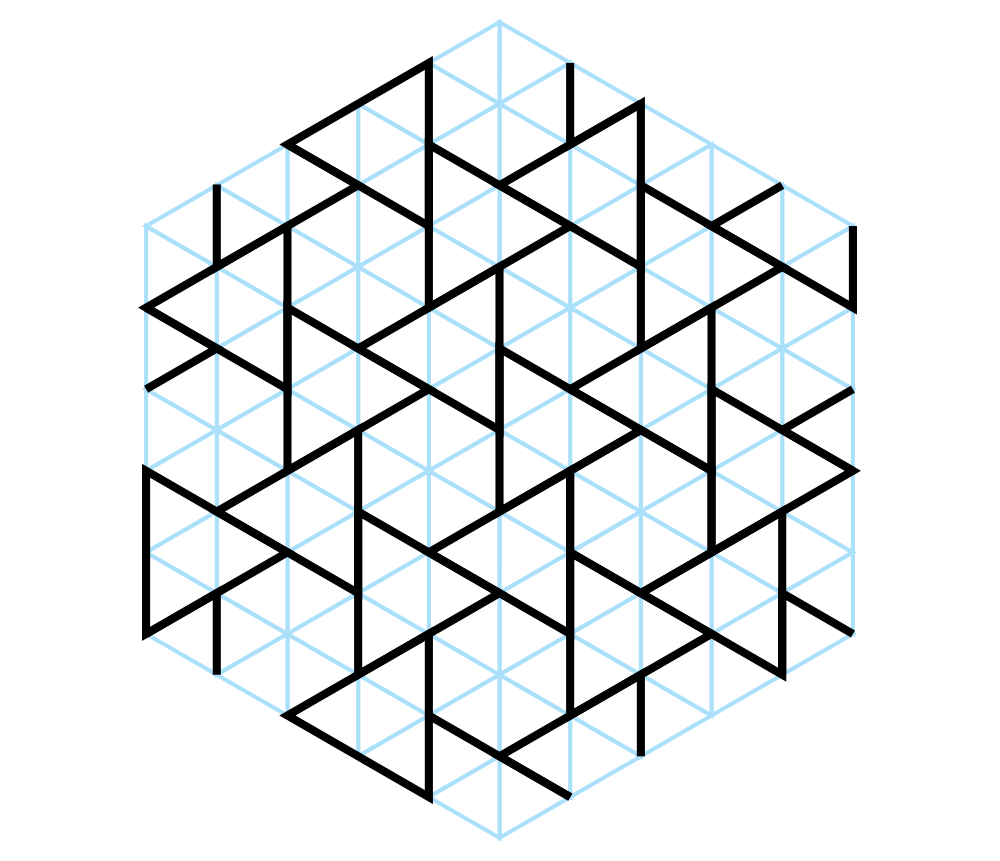

The second grid is based on triangles5:

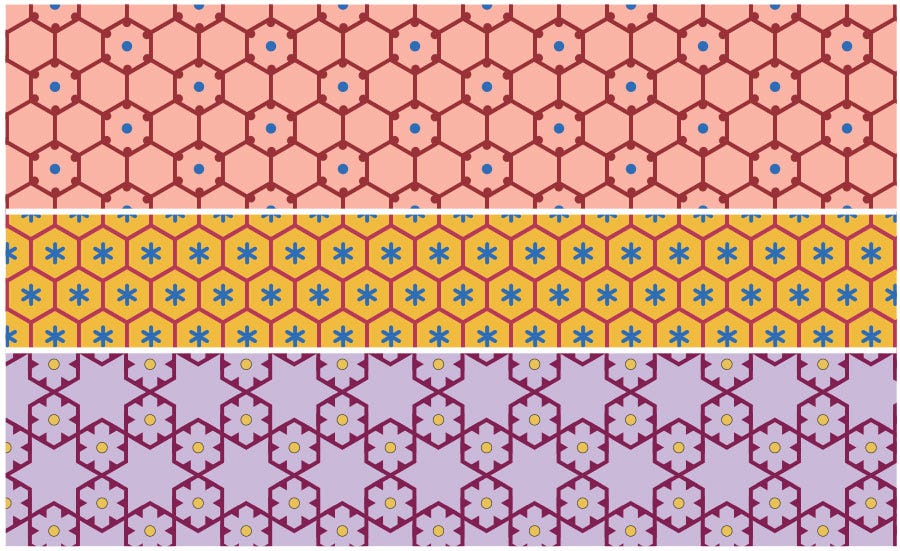

This is an enormously versatile base, but its simplest expression is tessellating hexagons. By the way the downright wonky pattern on the well, below right, clearly shows the freehand process – here the patterned hexagons were drawn first and then joined up, but the spacing was a little bit off and the result not quite as expected.

Interestingly, this simplest version is used very sparingly, in two iterations and exactly three places. I expect the artist was conscious that its very simplicity would make the repetitiveness tediously obvious to the reader – or he just found it too boring to work with, as there’s only so much you can do to vary it. If I had to fill a book with freehand patterns, I’d want to make it fun for myself too.

The second take on this grid is shown in the yellow robe and blue cushion below.

It looks trickier than it is, but it does require a lot more focus to draw freehand, and perhaps that’s why we only see it three times.

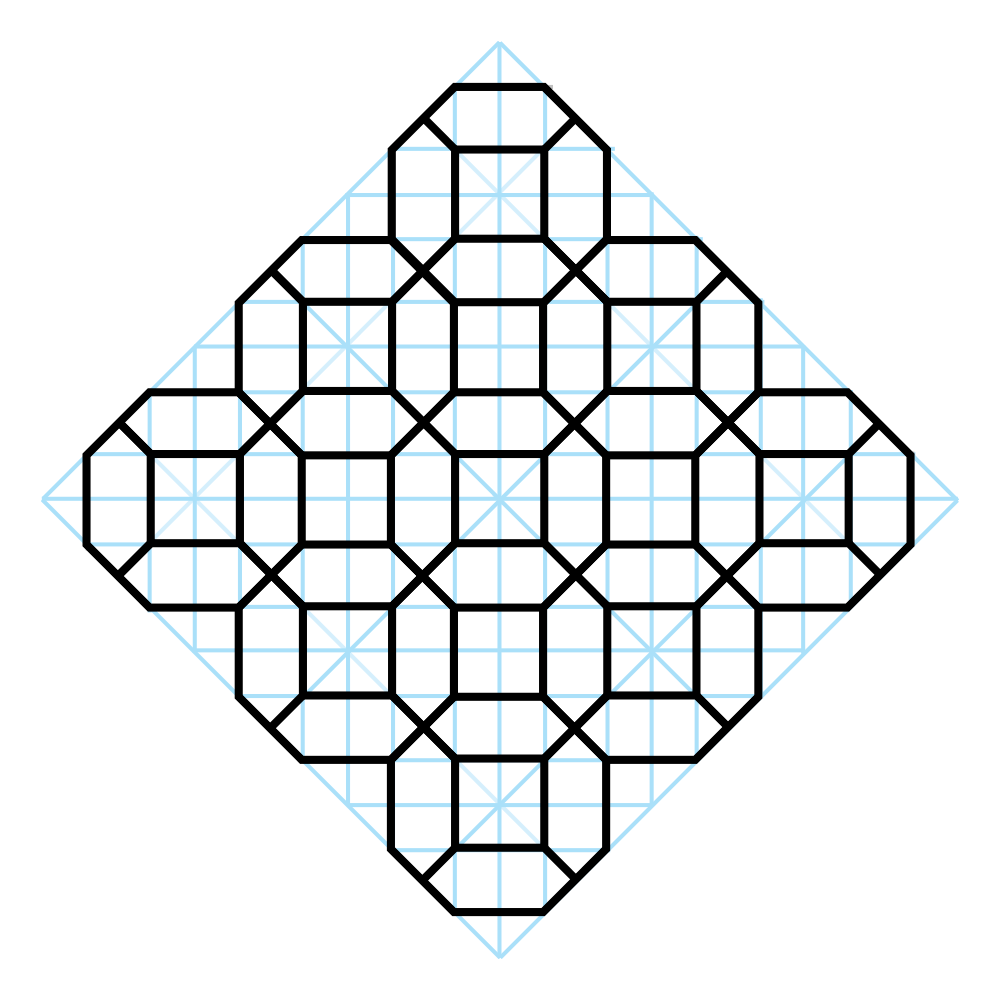

The triangle-base pattern that recurs the most is actually the most intricate to construct (though paradoxically easy to draw freehand on a small scale) .

Above I only showed the finished grid of triangles, but the added steps that produce this pattern require the full subgrid to be visible, so this is the simplest diagram I can offer:

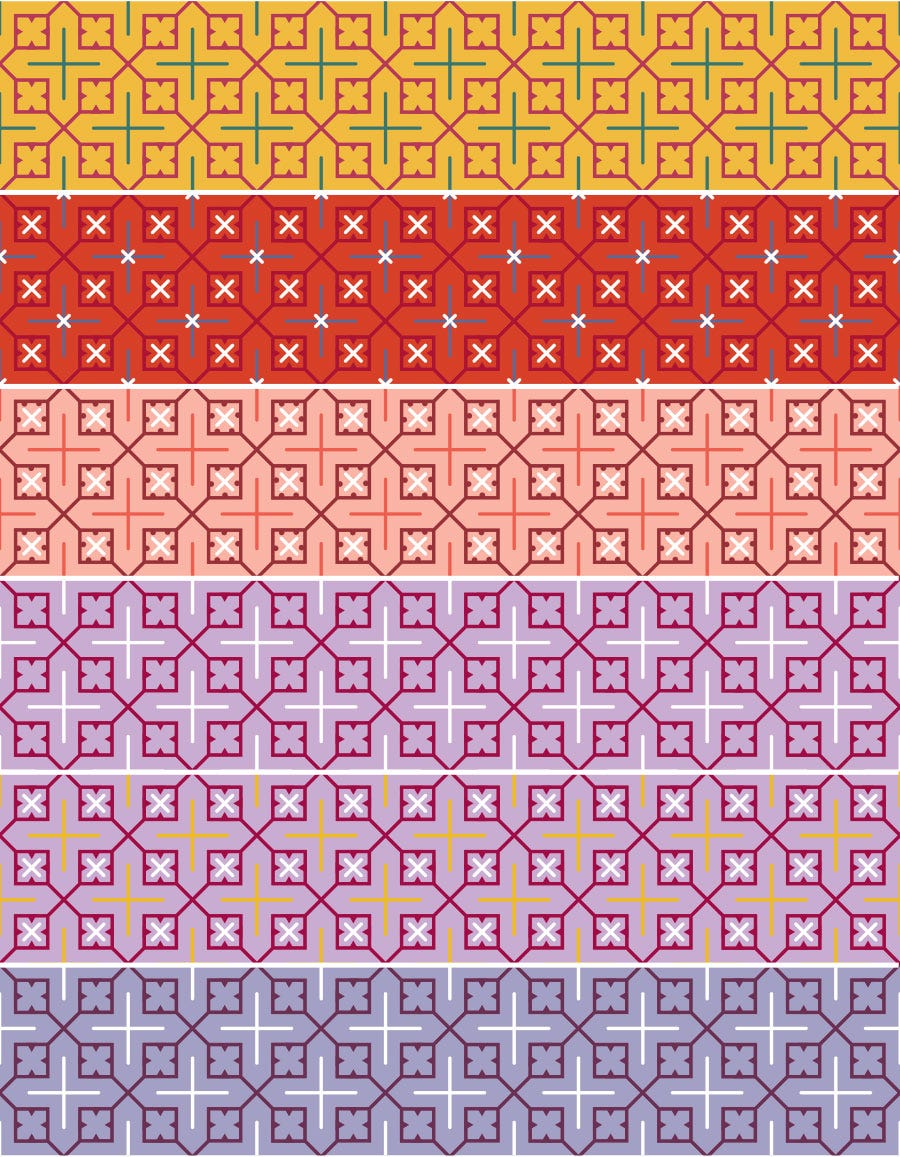

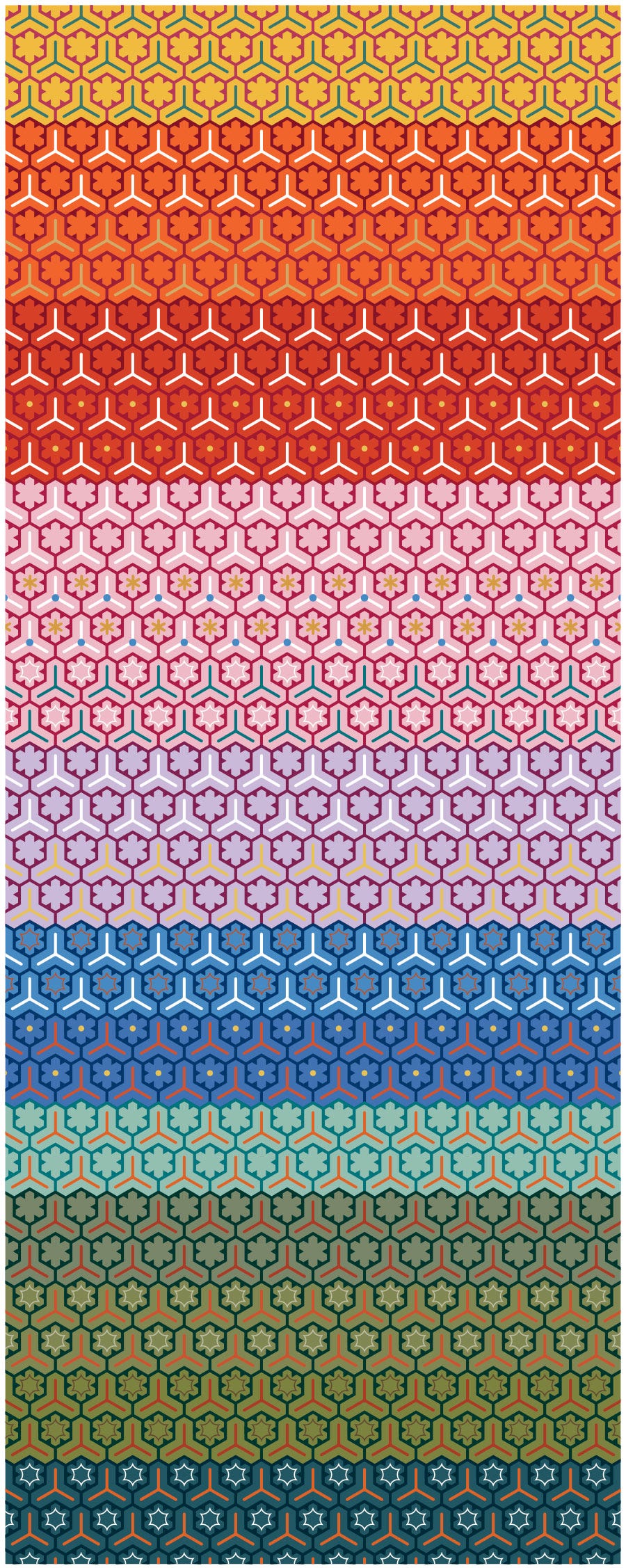

The full collection is rather glorious:

This completes this introduction to diapering, but I have exciting plans for this topic, using it as a thread to take us through unexpected areas.

Source for all manuscript images: Bibliothèque nationale de France. Département des manuscrits. Arabe 2583.

Identifier : ark:/12148/btv1b84229574

All patterns redrawn and diagrams created by myself.

The date is uncertain, as the last paragraph indicated the work was completed in the year 700H (1322 AD) but the last few pages were done by a different person and look newer than the rest.

There are more patterns in the illustrations, but I’m only tackling the real diapers, which are repeated without modification. In contrast, the biomorphic (plant-based) patterns are organic, with no fixed repeating unit, and they sometimes adapt to the shape being filled, which is not how diapers behave.

I had wanted to briefly show how to construct of this grid but it would have made no sense without a long tutorial that would have taken over. If you really want to try your hand at geometry, there are detailed instructions for this grid, and the patterns derived from it, in my print-at-home booklet The Grid of Squares available here.

Cf. note 4; these are covered in The Grid of Triangles (but note it doesn’t include the very last pattern shown in this post).

Very cool design. Unfortunate naming, perhaps, but it's not the only phenomenon out there to "suffer" from that. Beautiful examples too. Perhaps this is a typical guy observation, but I dig the guy shaking the huge scorpions. :D (is he a Mongol?)

So interesting! Thanks. May I inquire about the title of this piece? I don’t quite get it...