I’ve been getting an unexpected influx of new subscribers and I want to say welcome to everyone! The format of Caravanserai has been on my mind. The paywalled archive was meant to encourage subscriptions, but there is a lot of original research and material in there, and at the end of the day I’d rather it could be accessed, referred to and cited freely (with credit of course please!) So I’m dropping the paywall: you can now all access the full archive, anytime. Instead I will rely on people’s goodwill to take out paid subscriptions if and when they can, to support my independent research. I will also endeavour to post exclusives for paid subscribers from time to time. Now, on to today’s topic…

Some time ago, I was examining the script of a manuscript I randomly found while browsing early Islamic items in the digital collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. I noticed something very unusual about this script’s vocalisation – unheard of, even. Before I go any further, below is a brief primer about this aspect of the Arabic script, for the sake of anyone not familiar with it. If you already know what ḥarakāt are, you can skip this and scroll down to go straight to “The Forgotten”.

Arabic vowel marks

This is a quick and concise guide to cover only the marks that interest us in this post, as a full lesson on vocalisation would be both enormous and overwhelming.

Like other Semitic alphabets, the Arabic script only writes consonants. Words are vocalised by the addition of vowel marks called ḥarakāt1 that were always, and still are, quite optional in most contexts, as a literate speaker would intuitively know how to vocalise2. The Quran is one text that is usually vocalised to the extreme in order to prevent any deviation, and also has its own range of extra symbols to guide recitation.

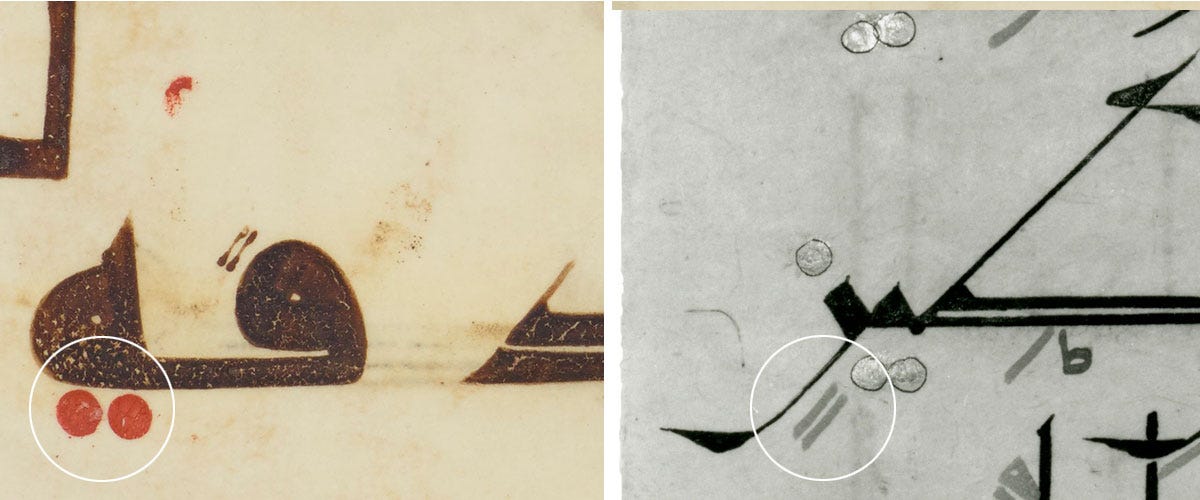

The ḥarakāt underwent their own evolution, from simple red dots only differentiated by their position, to the array of small symbols used today. It was by no means a linear evolution, so in the illustrations below I’m simply showing two snapshots: one very simple system that was used around the 10th century, and another, a couple of centuries later, where the signs have pretty much reached the form they still have today. These are the marks we’re concerned with:

FATḤA

Sound: short /a/ as in cat.

Started as a red dot above the letter, ended up as a diagonal (sometimes horizontal) dash above the letter.

KASRA

Sound: short /i/ as in be.

Started as a red dot below the letter, ended up as a diagonal (sometimes horizontal) dash below the letter.

DAMMA

Sound: short /u/ as in put.

Started as a red dot on the baseline, ended up as miniature و (wā) above the letter.

TANWĪN

Sometimes, for grammatical reasons, the final vowel sound (a, u or i) of a word is made to end in -n. This is indicated by doubling the ḥaraka:

Superscript Alif: This symbol indicates an alif or long /aː/ should be read even though it’s not actually written. This absence, known as scriptio defectiva, is a leftover from archaic Arabic spelling3 and today we still use words that were too old and ingrained for their spelling to be updated, a prime example of which is Allah اللّه.

The superscript alif started as a full-sized alif added in a different colour where it’s meant to be read:

Finally let me mention these additional symbols which did not exist at all in the older system: the shadda (shaped like a little W) which doubles the sound, sukūn (blue circle) which indicates a letter is not voiced, and hamza which is a glottal stop.

These are the most used and most essential vocalisation marks, but by no means the only ones, and other have come and gone, as we’re about to see.

The Forgotten

Getting back to our manuscript: BNF Arabe 6430 is (tentatively) dated to the 12th century, its provenance unknown but likely from the Eastern Islamic world, as it’s written in a script characteristic of Persian-influence lands. It’s often referred to as NS (“New Style”) but I firmly stand by the older and more useful designation: Eastern Kufi, itself a sizeable family of closely related styles. One characteristic of EK is that in contrast with its loosely vocalised forebears, it is always completely vocalised, regardless of necessity.

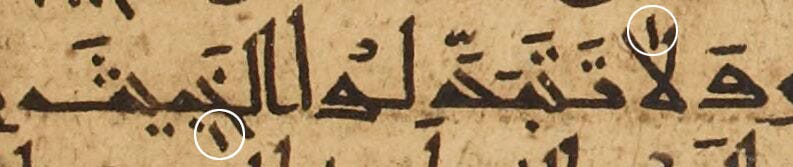

This is the case here, even though the 18 lines of text fit in a box that is 133x109mm – just a little shorter and broader than my iPhone. It’s therefore a tiny book, and the amount of detail is remarkable. We can spot here all the ḥarakāt we might expect, in a form close enough to modern norm as to be immediately recognisable:

The only missing one is the sukūn. “But there’s a red one in the second image,” you might think – I’ll get back to that one. For now, ignore the red marks.

In addition to the usual range, there are the surprises: ḥarakāt that are now completely extinct – not evolved in form, but completely abandoned.

Superscript alif - or is it?

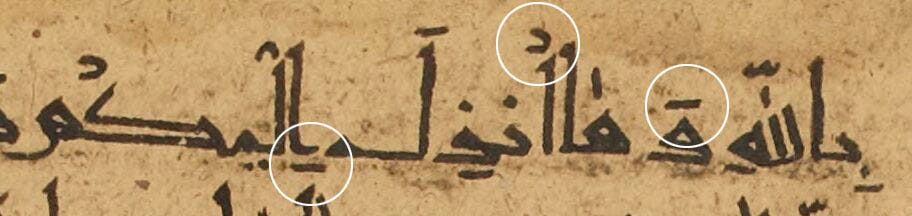

This short vertical dash miniature alif very much looks like one, and in the word Allah (first image) it is used as such.

However, most of the time it’s used in a subtly different way: just before an actual alif, rather than instead of one. It still indicates a long ā sound, but its presence can be considered redundant.

Looking carefully at the text, this same symbol is also used under the word, before the letter yā, where it’s clearly meant to indicate a long ī sound.

Today, neither of these situations require a symbol (they are the default reading in the absence of another indication), and in a hyper-vocalised text we would just use a regular fatḥa and kasra, respectively. This is therefore already one special symbol that’s gone, only surviving in the slightly different superscript alif.

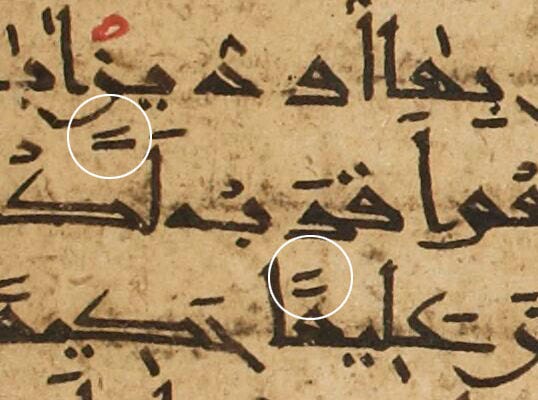

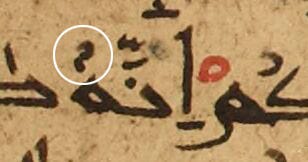

Long damma

If there are signs for long fatḥa and kasra, shouldn’t there logically be one for long damma as well? There is!

I couldn’t identify the sign at first because we would normally only have a brief sound at the end of a word, but it turns out that in Classical Arabic the -hu of 3rd person is lengthened to -hū after a short vowel4. The set of long vowels is therefore complete with this wholly original symbol.

Diphthong markers

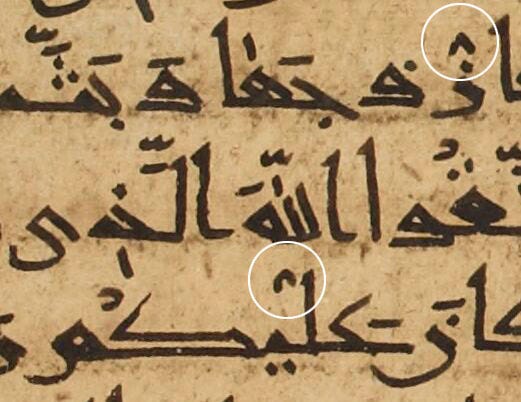

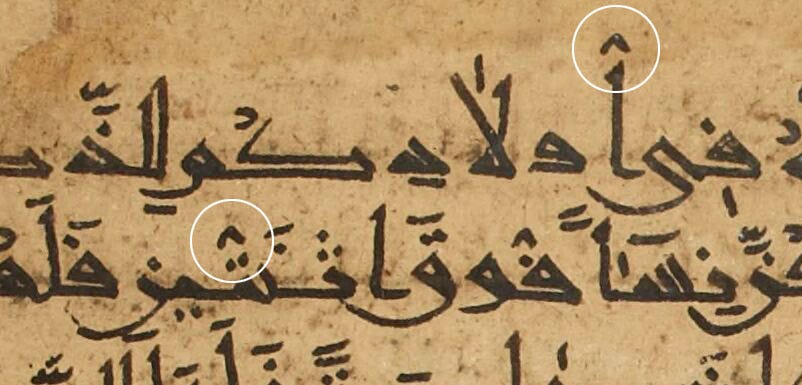

Here’s the real exciting discovery: this horseshoe-shaped mark (sometimes sharp like an inverted V, but that’s incidental).

Based on its usage, there is no doubt: this sign indicates the sound that results from having a fatḥa before the letters wāw و or yā ي: the sound “aw” or “ay”, respectively. I have no idea what this sign might have been called, because there’s no description of it I know of, I’ve never encountered any mention of such a thing, and I don’t believe it’s ever been observed anywhere else. It must have been short-lived, and unless it turns up in another manuscript, it could be an experiment that was limited to this particular one, which I happened to be looking at more closely than usual.

So what about the red signs?

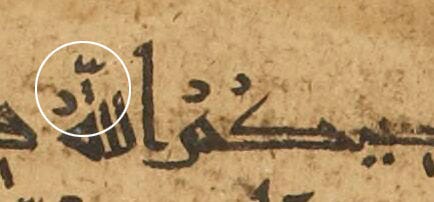

The description of this manuscript on Gallica states that "some sukūn and shadda are written in red ink". This is wrong, and such descriptions often are so they should always be scrutinised5 The red marks are there most probably for recitation, and certainly not for vocalisation. This is borne out in the images below, where you can see the circled shadda are falling on the first letter of the word, which can never actually happen.

And why would some shadda be in black and others in red, while the only sukūn are red? The only logical answer is that this is a different layer of information, and in a quranic context that means recitation. It’s easy to assign emphasis to the shadda and pause for breath to the sukūn; I’m less sure of what the damma-shaped sign means, but it’s another story anyway.

It doesn’t matter how many manuscripts I examine, I always find surprises… I hope this intrigued you!

"Movements”, in other words they animate the voiceless script by adding the voice.

Note I said “literate”, not “native”. Natively, people speak their local Arabic dialect. These are numerous and as a rule they are simpler than the formal Arabic used in writing (referred to as fuṣḥa or naḥawi). For instance in my native Lebanese, we mostly don’t vocalise the end of words in daily speech, so the grammatical endings of formal Arabic have to be acquired through education.

There’s a myth that Arabic hasn’t changed, grammatically or orthographically, since the earliest days. Spoilers: BOY has it changed. As to the “unwritten Alif”, I go into a little more detail in my introduction to Kufi, under “Notes for readers of Modern Arabic”.

I owe this piece of info to Marijn van Putten, as I know nothing of Classical Arabic. Indeed few people do.

No shade intended! The person making the catalogue entry doesn’t necessarily have the in-depth knowledge required to recognise precisely what they’re looking at. But that doesn’t make erroneous statements less problematic when they’re repeated without question.

This post very much did intrigue me! I'm glad to see you're getting more subscribers. I always learn something new when I read your posts.

On a Substack note, I've thought about reducing the paywall too. It ends up being more of a hindrance than anything. I only keep it now because I've gotten prolific, so I have to be merciful to people's inboxes. :-)

Fantastic article, Joumana, liked it a lot. I really enjoyed the insights shared in the article. It's fascinating how these artistic details contribute to the overall beauty and complexity of the script.

I'm also inspired to delve deeper into this topic and share my findings on Thuluth script, focusing on the intricate balance between form and function in calligraphy. It's amazing to see how the decorative elements evolved over time. Definitely recommend your publication.