Last month, in the context of the workshop “Medieval Pigments and Modern Practice”, I gave a brief talk about my experience of foraging in place and how it affected my artistic practice. Here’s a slightly more developed write-up of that talk, as I know many of you have an interest in this topic.

Some years back, during my yearly visits to my home in Lebanon, I started paying closer attention to the soil1. In many places the vegetation cover is quite scarce, so natural ochres are very visible and accessible.

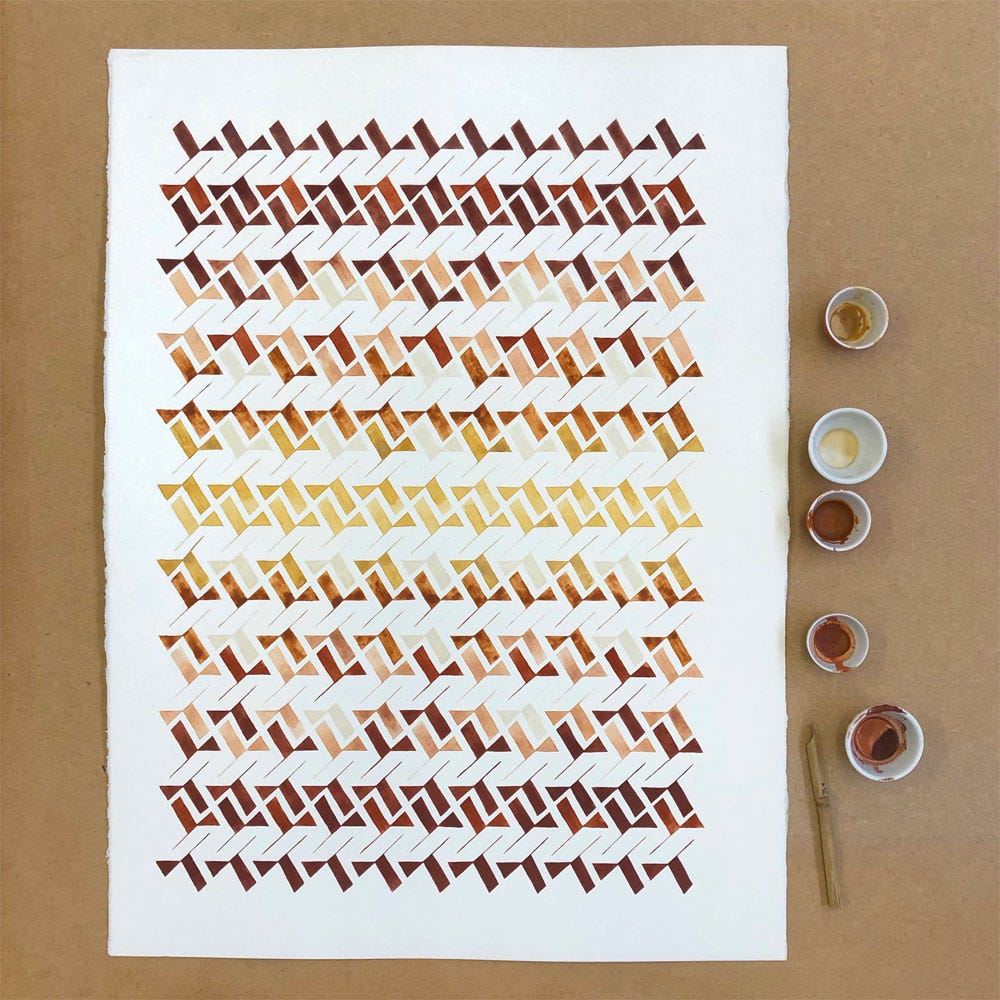

The landscape is largely sandstone, with some clay and chalk, and there’s a vast palette of earth colours. Hues range from cream to deep brown and yellow to red, with saturation varying from muted to intense. I already used historical pigments in my practice and I knew how to extract pigment from the raw mineral, so I became very interested in collecting samples directly from the earth and finding out what palette they yielded.

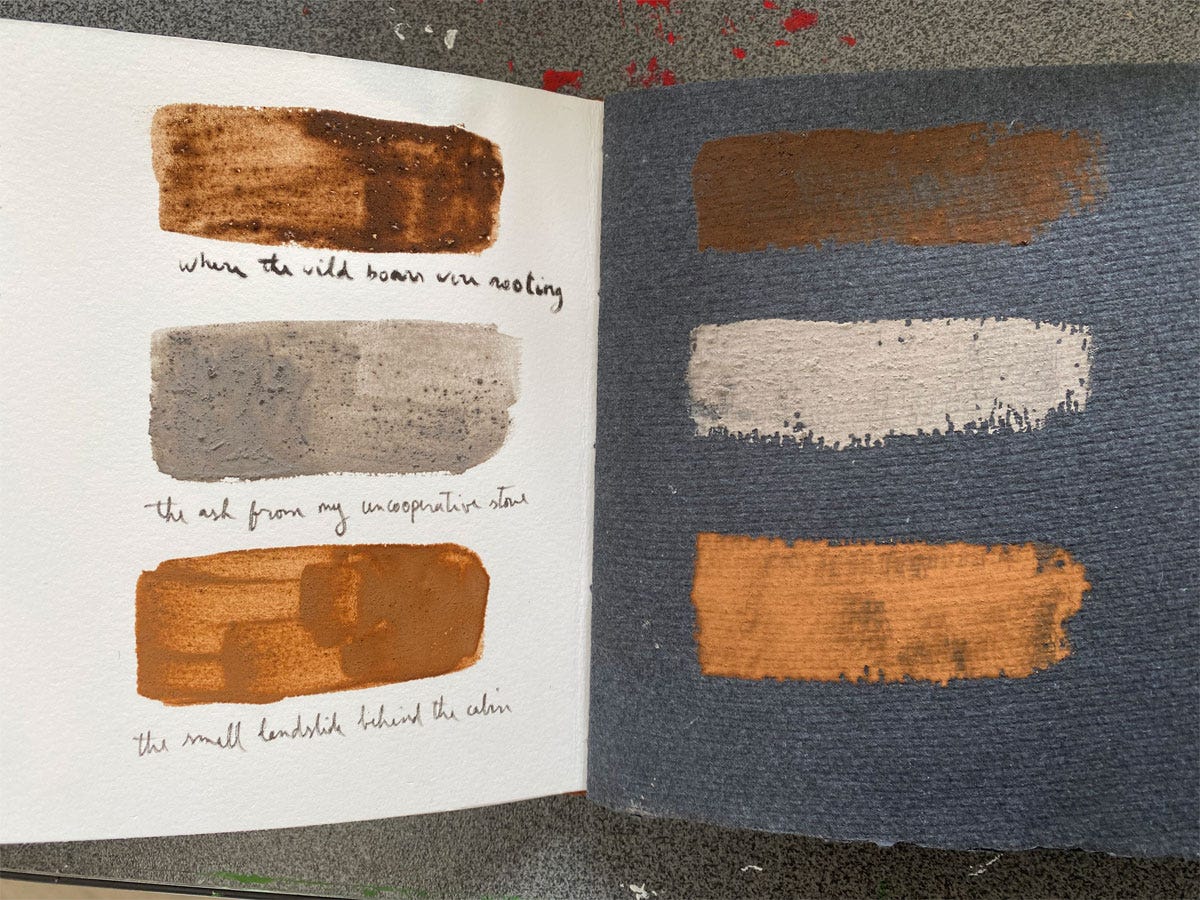

Once the iron oxides have been separated from other components through the process of levigation, the resulting pigment is hardly ever the same colour as the original rock. Roses and purples only look that way because whitish or bluish limestone is mixed in: after washing they come out in red-browns or orange-browns. So it’s always a surprise, though with experience you start getting a sense for the likely result.

Below is a small sample of my pigments from back home, showing off the range — though I have four times as many by now.

What I miss the most about home are the mountains, so integrating these pigments in my work was a way for me to bring the mountains with me.

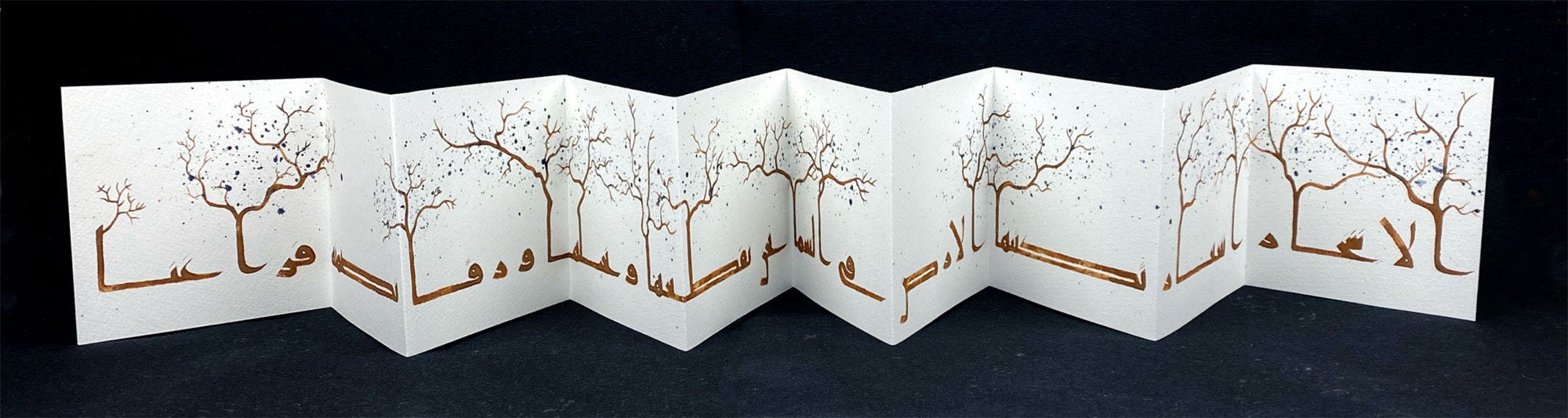

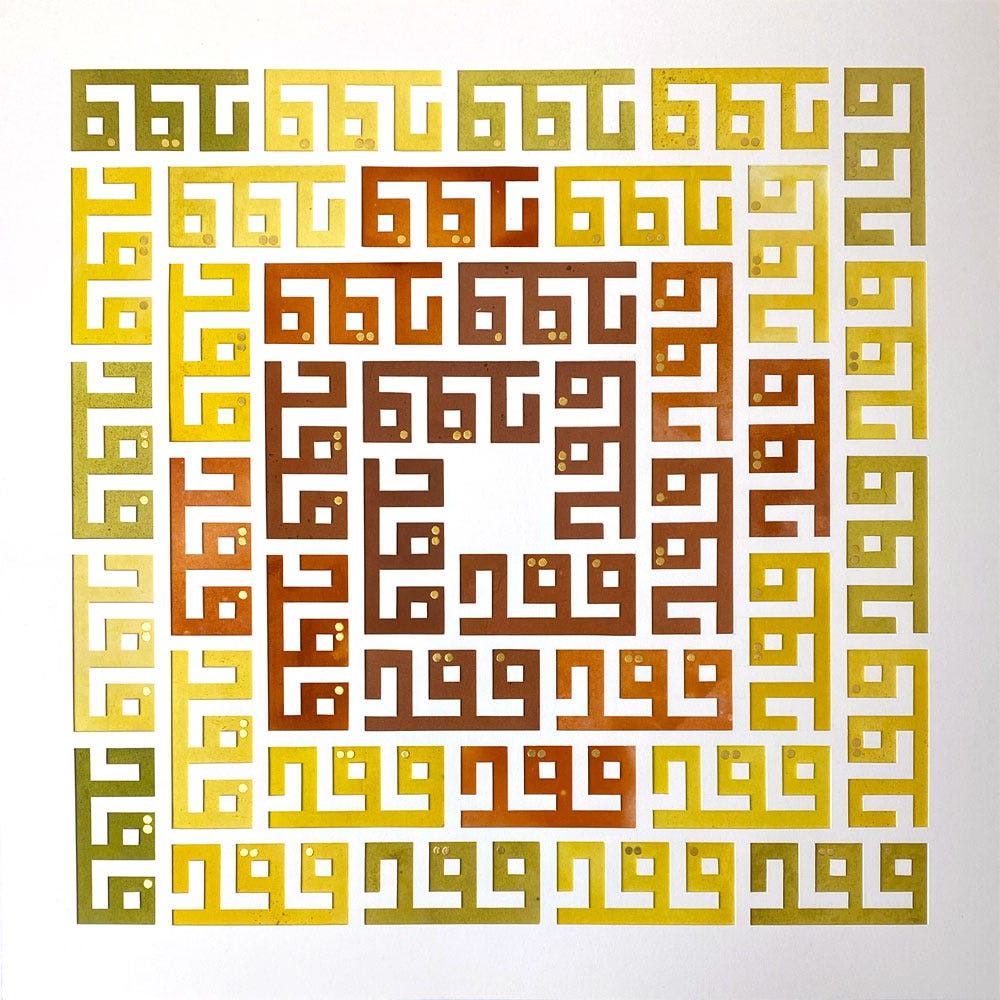

One site, quite high up above the tree line, yielded so many colours that it inspired the following piece: Out of the Untamed Land2.

I like to call it “single origin” because the six earth pigments used for it were gathered in the same spot, on the same day. The word that makes up the pattern is related: barr برّ, which denotes the land, the earth, the wilderness, its adjective barri meaning untamed, feral, wild; at the same time, the same word pronounced birr means great love, devotion and reverence.

A significant point about this piece is that it marked a change in the usual order of things: instead of acquiring the materials I needed to realise idea, I found myself looking for ideas that would make use of the materials I had acquired.

I wasn’t limited to foraging earth pigments either. During the pandemic lockdowns, with public transport off-limits, I walked to my studio two or three times a week. It took about an hour each way and took me past hedgerows, marshes and eventually woodland and a corner of the Olympic park. This semi-urban landscape was incredibly rich with plants that had dyeing potential, and an idea started to take shape.

I had just published a book on medieval middle-eastern materials3, most of which come from distant lands and are often precious. Now I was thinking of following it up with another: Wild Inks & Paints, dealing with art materials that you could collect wherever you are. For most of us, these would come from plants.

Through collecting and processing plants throughout a whole year, through research and experimentation, I learned a lot about biochromes4, their chemistry, what modifies them… Above all I experienced how transient most organic colours are, some more than others.

Knowing that foraged plant colours are short-lived, an artist would normally avoid using them in anything but ephemera. The last thing you want is to sell an art piece only for it to fade within months of being put up on a wall. But whether this evanescence should be considered a drawback or a quality, is a matter of perspective. Personally, it got me meditating on our expectations of artwork, the received wisdom that once finished it should never change. What if the work was intended to change with time? What if we accept that change and mortality are valuable aspects of reality? With a proper understanding of organic colours, I could work their fugitive quality into a piece, and insure that however much they fade, the work remains an art piece5.

My first venture into this concept was my piece Loss6. I gathered my palette during a stay in Kent, one late summer day: St John’s wort, coreopsis, marigold, goldenrod, yarrow.

Rather than make inks, I used these to dye strips of paper, which gives a different result and extends the colour’s life somewhat.

These strips were attached to the back of my hand-cut composition.

I often use layers of cut paper to introduce dimension to my pieces, and in this case it was key to the piece’s longevity: the colours will fade gently over time. They will probably never completely vanish, but even if they did, they would leave behind a sculptural piece evocative of the once-painted Greek temples that time has stripped of all pigment. Meanwhile the dots, being gold, would never fade or discolour but only become more visible: in this meditation on Loss, they are there to symbolise seeds that bide their time unharmed until it’s time for rebirth.

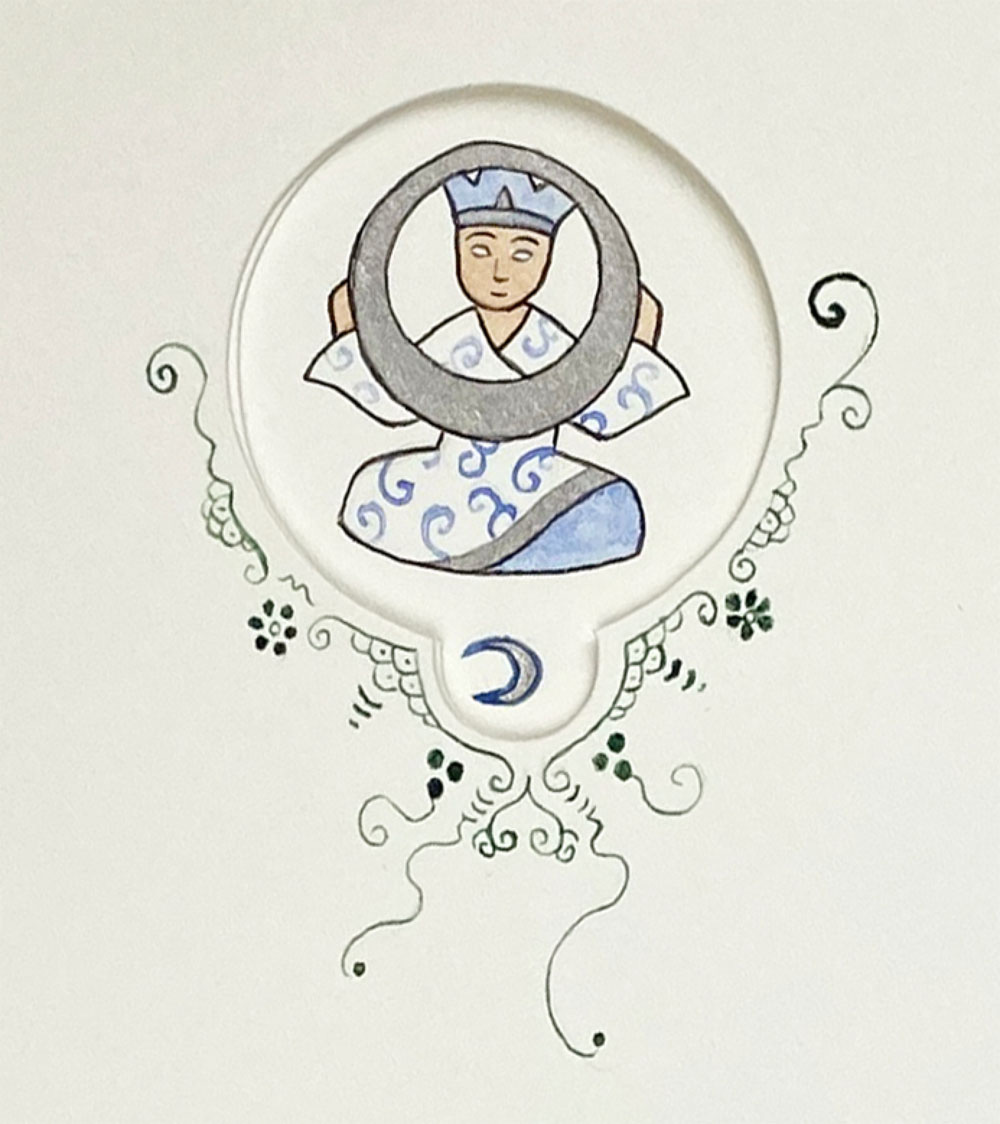

Another example, Blessings Everlasting7, made use both of permanent and impermanent colours.

This piece was inspired by the Islamic tradition of decorating surfaces with words expressing blessings and good wishes. Examples of these are “good fortune”, “good health”, “joy”, but also more questionable notions such as “wealth”, “dominion”, “victory” and so on. Eleven historically-used words make up this composition. Some (those I consider illusory and meaningless) are painted in light-sensitive plant colours, and others are painted in immutable mineral pigment. The photo above shows it as it was when freshly painted. I then deliberately exposed it to natural light for a year, at the end of which this is how it looked:

The process will continue selectively, until the last of the plant colours has gone, but the mineral pigments, which form words such as “goodness” and “compassion”, will remain forever, among the faded ghosts of worthless pursuits.8

Since collecting earths in Lebanon, I’ve also been very interested in localised palettes: to make use of the colours found within a small area of land. Between organic and inorganic colours, every place has its own subtly unique palette, and I like to think that a localised set of colours will always be harmonious because of the shared ground chemistry. And even when it’s not possible to create a piece without using imported materials, I really like to integrate at least some locally gathered colour to create a physical connection to place.

As an example of this: Last winter I went on an art residency on a rural estate in Andalucia9. When I arrived, I was struck by the sight of the “dancing” holm oaks that covered the entire finca, being grown to feed the region’s famous Iberian pigs.

The trees brought to mind a quote by my countryman Khalil Gibran: “Trees are poems the earth writes upon the sky…” The earth they grow on, under the thin grass cover, is good clay that is highly pigmented.

The shape of the individual trees I encountered daily, the earth they grow on, and my own Kufi calligraphy: This combination quickly became a simple but rather lovely artist book, with indigo dye I’d brought along supplying some spattered blue foliage.

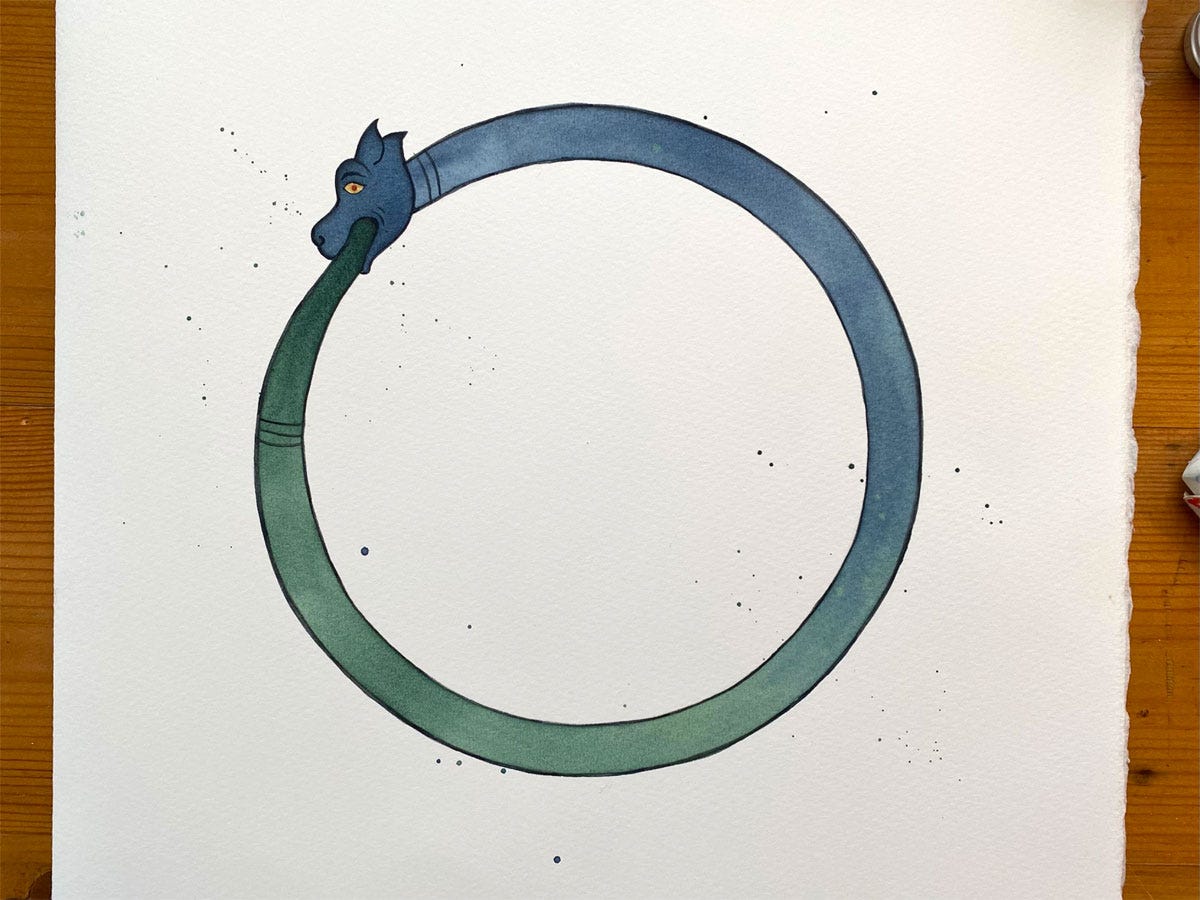

To finish, here’s a glimpse from an ambitious project I have only just finished, but not published yet. I spent the last autumn term as a visiting research fellow in Creative Arts at Merton College in Oxford, working on an elaborate artist book. The theme of the book is strongly related to the college, so they were keen for me to weave in a physical connection via ink made from the gardens’ offerings. I came in summer to meet up with the head gardener and collect a few plants.

The wallflowers didn’t turn out the way I expected10, but irises produced a gorgeous blue, and camassia, which were new to me, a lovely teal.

Plant colours keep much better in a manuscript than they do on a wall, because they’re protected from light and ambient changes. In fact iris green is a well-known historical colour, used in manuscript illumination in Western Europe. So I didn’t hesitate to use these inks, which can make extra fine lines, in my manuscript alongside medieval mineral pigments.

As a brief conclusion, my relationship to foraged colours is always evolving as I explore the various ways in which they can enhance or make an art piece. But their use is now integral to my art practice, rooting it into something solid and real – the earth under my feet, the change of the seasons – and I can no longer imagine working any other way.

I wrote about this at length in my very first Caravanserai post: Starting with Earth.

More info and images on the website.

Inks & Paints of the Middle East: A Handbook of Abbasid Art Technology. At the moment the print version is out of stock pending revision.

A better word for plant pigments, which are organic and soluble and don’t in any way behave like the solid mineral or inorganic pigments.

As opposed to a piece that will deteriorate beyond repair, which is what happens for instance when cheap paper, glues or paints are used without any regard for material reality.

More about Loss on the website.

More info and images on the website.

As an aside here and a warning to aspiring inkmakers, the first biochromes to vanish (within mere days) were saffron and turmeric. They left absolutely no trace behind, the ghosting being due to entirely to the gum arabic binder.

I wrote about this in more detail at the time: Art from the Land 1 and its sequel.

This is breathtaking! I loved the idea of planned 'obsolescence' incorporated into the Blessings Everlasting. As graphically compelling as the work is at its start, the selective fading of some colors after a year lends the image an ethereal beauty that could not have been achieved at the outset. This turns 'time' into an artist's tool--as valid as any paint brush, if meticulously utilized. I look forward to seeing more of your work.

The elegant beauty of your post is a lodestar for me. Beyond (or beneath) that, this is what I need to start using the collection of local pigments I have been collecting and to prepare for gathering local wildflower this growing season. To start not with how they can be used as support, but with the pigments themselves, the idea for form that they inspire out of their very being. I have one small canvas that I painted that way, but did not recognize until I read your words why it is the one I keep on view. I am so grateful that you share your work, your experience, and thoughts this way.