After my last post, the rest of my residency was equally fruitful and worth sharing.

Other than the indigo, I had brought leftover sappanwood (brazilwood) with me: I’d used it to make ink for workshops, and felt it still had a lot of colour in it so I left it to dry. I didn’t get around to using it for months, so I popped it into my suitcase and brought it along. After my indigo success, I decided to also dye some brazilwood squares.

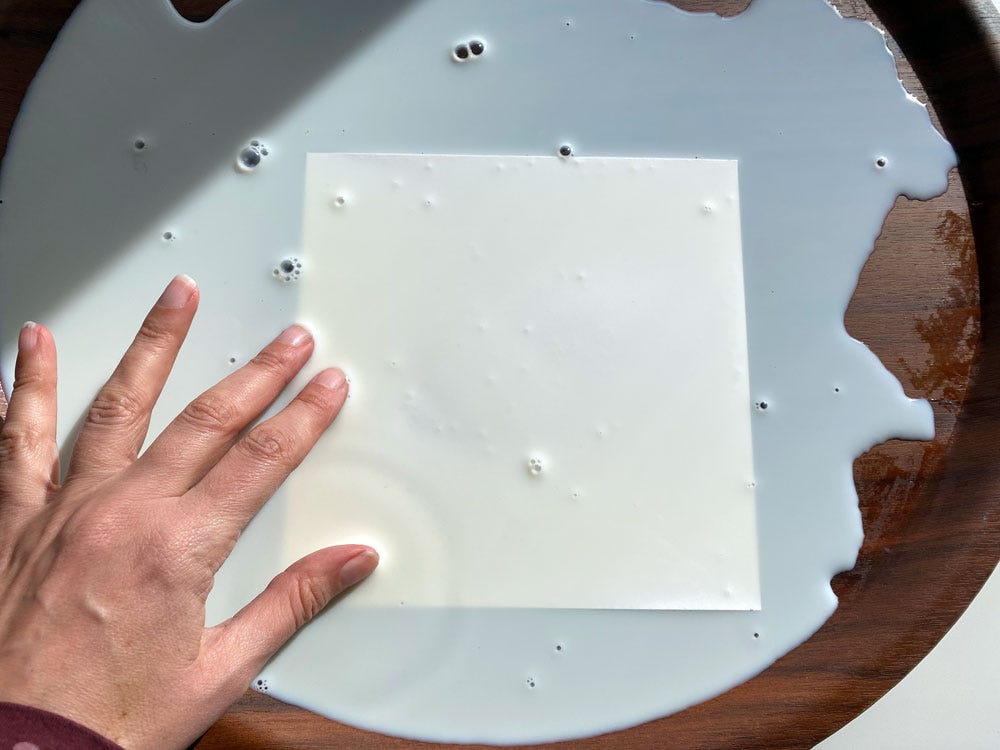

But first, I had to prepare the paper. Cellulose doesn’t take dyes very well, and in addition, the alkaline surface of acid-free art paper doesn’t deal well with an acidic dye like brazilwood. One way to make it more receptive was to coat it with milk1. I had only a shallow tray and a little mik at hand, but they did the job.

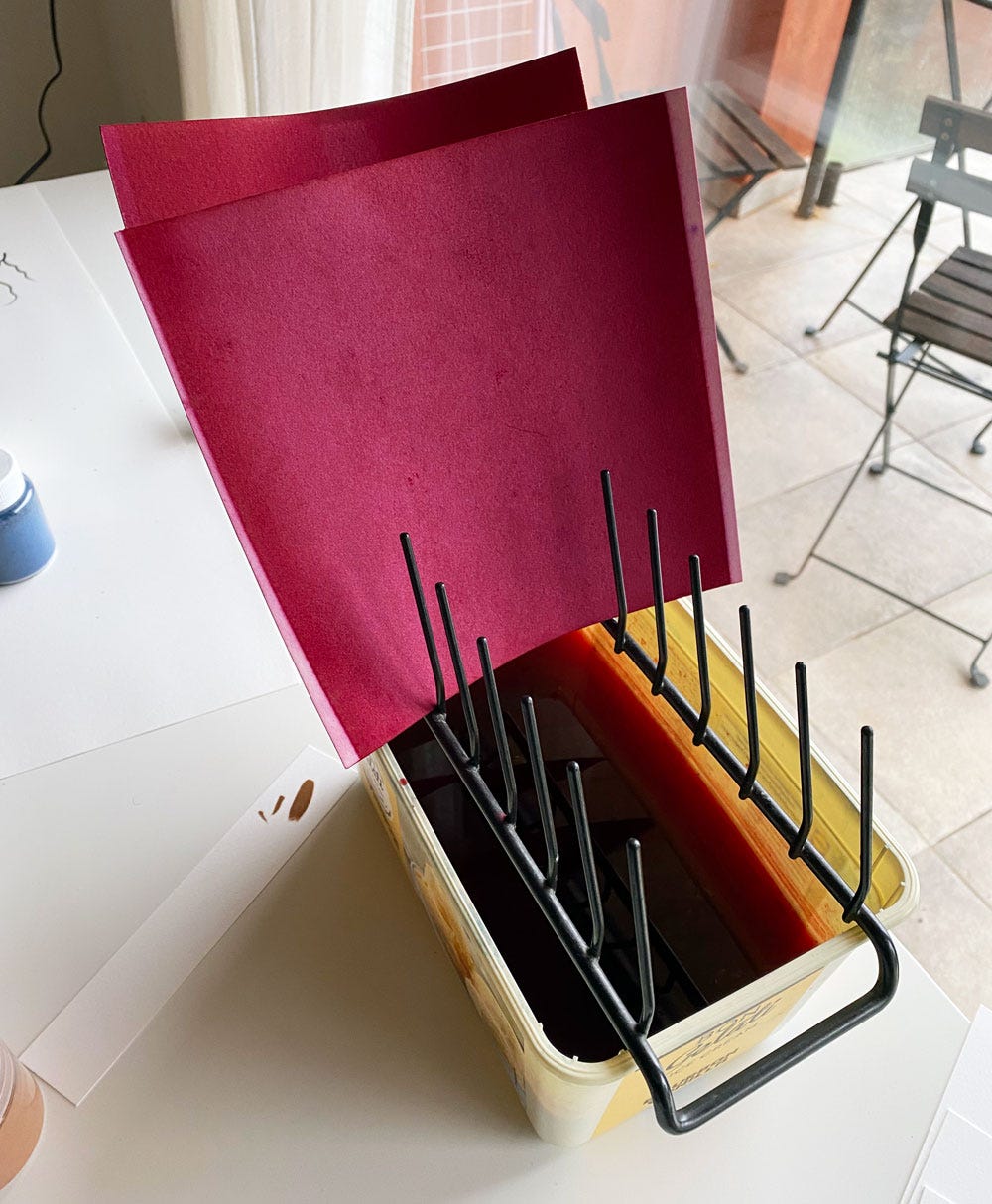

Once the paper was thoroughly dry, I left each square to soak overnight in the tub.

Because each paper had to be curved into a U-shape to fit in the tub, a lighter area has appeared on each of them in the centre where the curve was. This is a rather nice effect!

The greater excitement continued to come from the land itself, though. One unexpected sight nearby was a number of eucalyptus trees. They're planted because they grow so fast and I suppose that makes them good sources of firewood. It was the deep red bark that fascinated me, as it just falls off the tree to reveal bright yellow wood.

The bark being so thin, I thought it should be easy to extract colour from it so I soaked it overnight and then boiled it with soda ash.

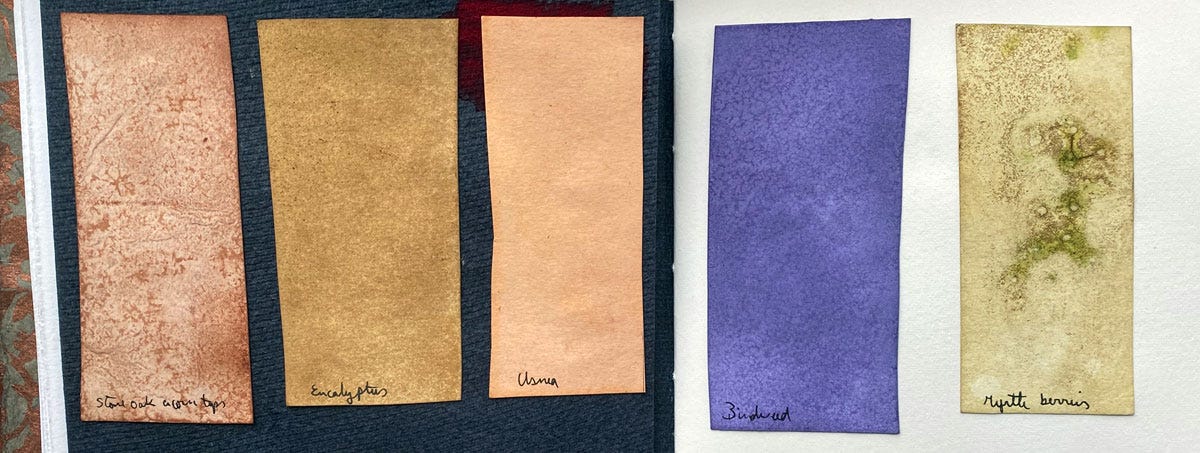

You can see the result below, something between the red bark and yellow wood. I looked up the use of eucalyptus bark in dyeing, and it doesn’t look like it can yield anything much brighter despite its promise. With more time I might have been able to soak the bark more and then concentrate the result, but based on my research I don’t think it would have made a spectacular difference.

Next to the eucalyptus swatch is one dyed with Usnea, a common type of lichen known as Old Man's Beard, by simply simmering it, and it also produced a rusty hue. This dyed paper quite nicely and I believe it is lightfast. I usually avoid using lichens because they take a decade to grow back and so many species are endangered now. But the ground of the finca was littered with twigs that broke off trees with lichen still attached, so I had plenty to work with from these doomed windfalls.

One evening I climbed up the ridge opposite the cabin, where I found a lovely old boundary wall. Standing on the wall, I could see Corteconceptión, the nearest village, which is the handful of white houses in this photo. I walked there for the first time after my last post, and this proved to be a rich source of discovery.

I completely fell in love with that walk, a winding mile or so among groves of olive trees or cork oaks separated by stone walls, with various farm animals roaming freely under the trees.

Cork oaks (Quercus suber) are an incredible sight. Sometimes the thick bark, which weighs nothing, falls off naturally, but in cases like this it's clearly been harvested by hand. The underwood is bright red, but turns black over time. To me this betrays the presence of iron, with oxidisation taking place once it’s uncovered!

I was excited to see cork oaks in person because they've come up, hidden behind the obscure word شوبر (which turned out to be uniquely Andalusian, and is remembered in Quercus suber), in the Treasures of the Select when I was translating it. In it it’s used to make a “red” ink, and I brought a couple of pieces back in the hope of testing them.

But I also encountered another tree that the Treasures brough to my attention: the strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo), locally known as madroño — مطرون in the text, not Arabic at all! It was a thrill to see the jewel-red fruits strewing the path and realise the tree was present along the way, but sadly nothing can be done with the fruit (other than savouring it). It is for its wood that it was mentioned by al-Qalalusi, as it’s remarkably hard and used for making pipes and small objects.

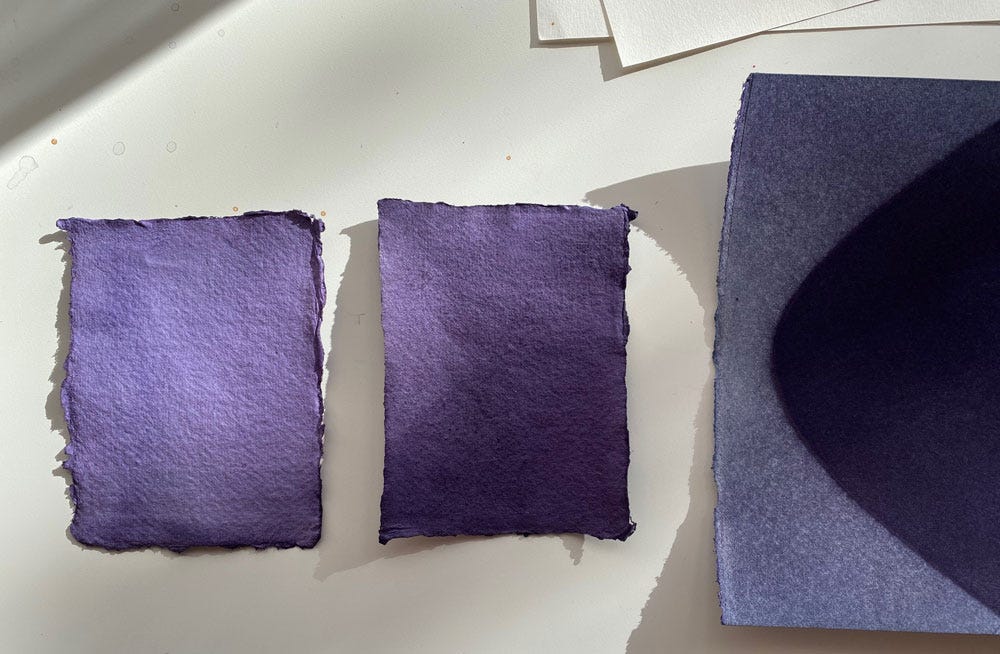

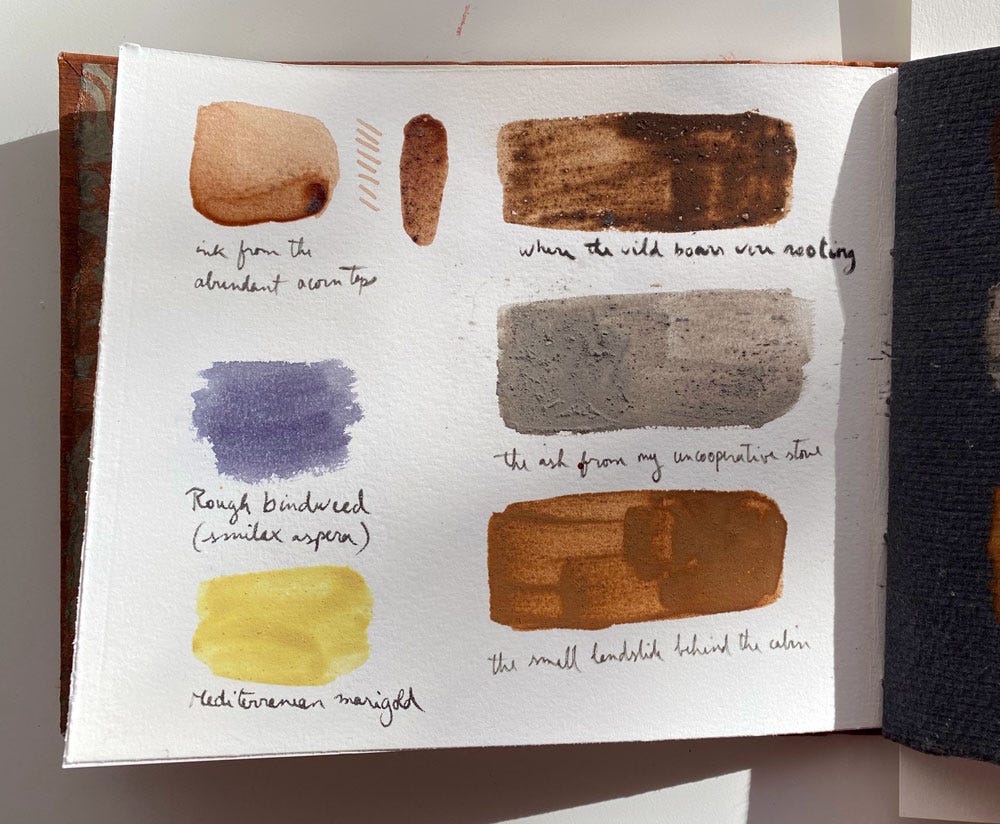

Smilax aspera or rough bindweed was another encounter on my walk, with abundant berries even at this time of year.

I tested a few before committing to boiling a batch... And sure enough, the usual anthocyanin bright purple came out. Anthocyanins are fun to extract, but very unstable and pH-sensitive, so I always take them with a grain of salt.

In the dyed swatches, note the colour disparity between the smaller khadi paper, which has a less alkaline surface and yields a purple result, and the watercolour paper (right) where the dye turns much more blue.

Incidentally, a few days in I realised the stove, which was my only way of keeping warm, was great to brew and reduce inks without using up gas...

Another walk, to the larger and more distant town of Aracena, brought me to a field of what I think were Mediterranean or corn marigold (Coleostephus myconis), of which I immediately gathered a handful to complete my palette.

There wasn't a lot, so I didn’t waste my time trying an ink, which I would have needed to reduce a great deal. Instead I directly made a lake with the extracted dye, which is done by causing the dye to precipitate. With yellows, this always gives a more opaque and substantial colour. As soon as I added the soda ash to the nearly clear dye, the colour turned into something like orange juice.

I dried it out as much as I could before mixing it into a watercolour. You can see the result below, under the bindweed ink. Notice also an additional brush of acorn ink, much darker than the original: I reduced the ink considerably to get this beautiful deep brown.

I have now just returned home after a couple of days in Seville (of which you’ll probably hear more in future). Alongside my material experiments, I worked on two more artist books during the rest of my stay, which I brought back to finish. So I’ll end with this beautiful sunrise from a few days ago…

I cover different methods of priming and sizing paper at length in Wild Inks & Paints.

Thank you for sharing all these beautiful lab and field notes...

I am not envious, or anything...

You are truly an alchemist!