Flashback to 2010, on one of those days where the fog swallows up the Lebanese mountains and makes you feel like you’re miles away from everything.

A friend picked me up for a short hike across a valley he knew fairly well. I enjoyed having wild earth under my feet—a rare commodity in such a small overurbanised country—but the view was pure cotton wool, and somehow we suddenly found ourselves outside an old abandoned monastery, as silent and spooky as you like.

I have no memory at all of how we found a way in, but in we went, curiosity overcoming the eerie atmosphere. Though I must say, after exploring the ground and lower ground floors, we took one look at the lowest and darkest level and decided we had run out of nerve.

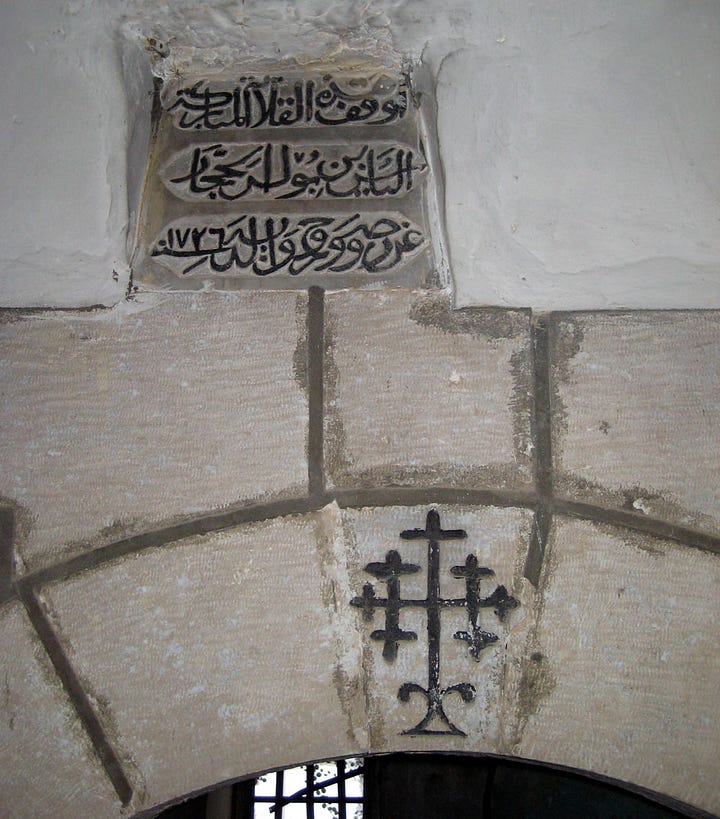

Those were the days “before”, when smart phones were still a rarity, but I was raised by a photographer so I never went anywhere without a camera—at the very least a low-res pocket digital camera as was the case on that day. All these years later, I’m very glad past me felt moved to capture the few, but unexpectedly diverse, decorative elements in that austere place. Nearly every keystone carried a cross design, but no two were the same.

The monks’ cells, with more cross designs, were below1. Inscriptions above the keystones, dated 1726, appear to commemorate patrons.

It was sad to see such an old place left to rot. The decorative patterns would surely have been worth a study, but hardly any of that was left other than this deteriorating plaster wall.

But the most interesting feature, and the main reason why I’m writing about this, was out in the courtyard.

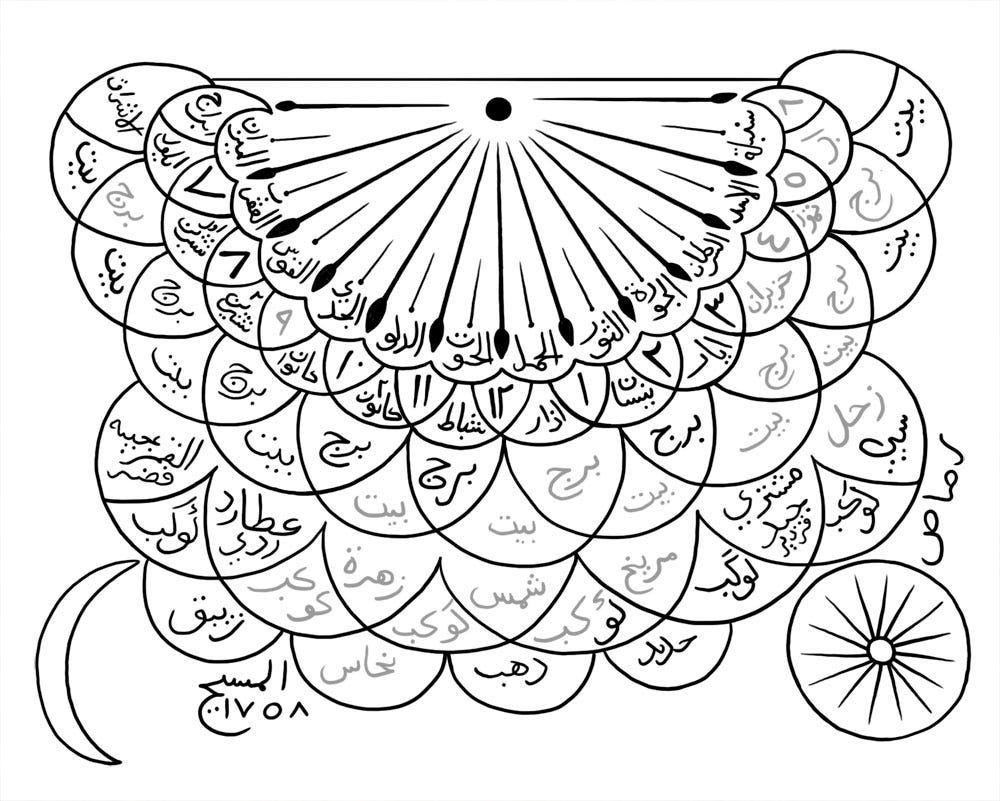

This sundial intrigued me more than anything else, and this was the best close-up I could get with my primitive camera.

At the time it looked to me much as it must look to you, awfully complicated for a simple time piece, and with layers of text to decipher. I meant to try and make sense of it, but by the time I finally took a closer look it was 8 years later: I had moved to London, started over, and was deep in researching medieval cosmology for a series of art pieces.

Which meant that by the time I returned to the sundial, I was in a position not only to decipher it, but also to fill in the missing text.

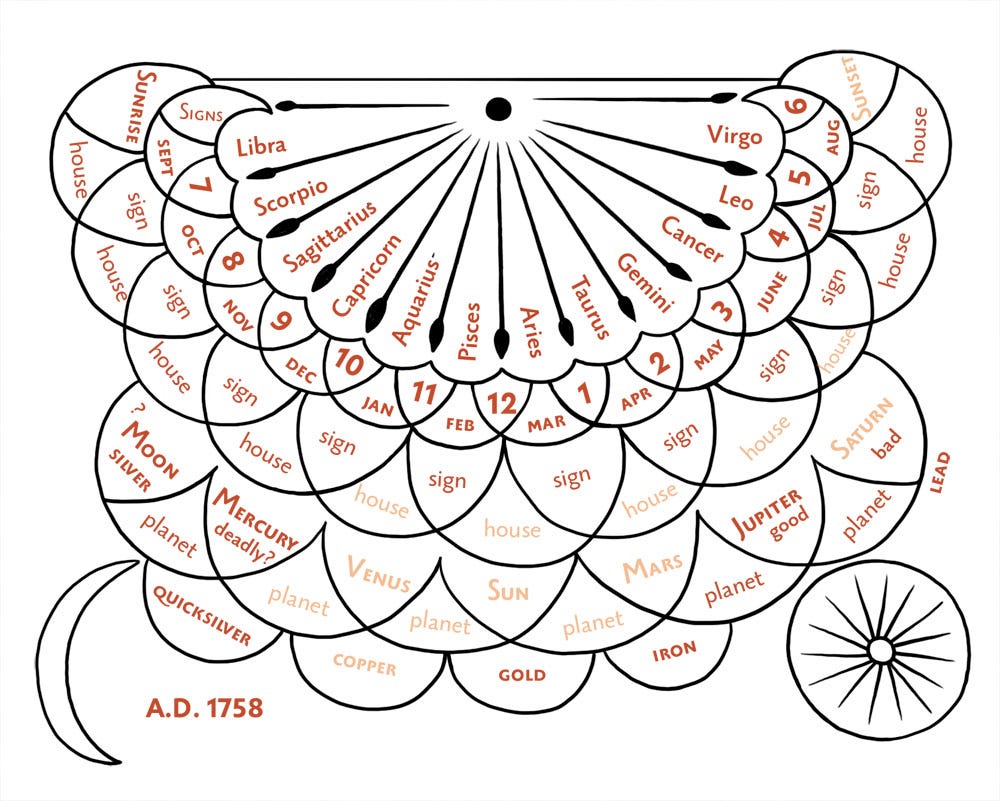

English translation:

It's not just a sundial, it's a pretty extensive astrological table complete with metal correspondences. There are even notes as to the nature of the planets’ influences (“good” for Jupiter, “bad” for Saturn, something that can translate as “deadly or destructive”2 for Mercury), but the Moon’s is very hard to read and the others are sadly lost—though easy to guess. Since Jupiter and Saturn are clearly set in their roles of “Great Benefic” and “Great Malefic” respectively, the others must follow suit along the same traditional lines.

The model of planetary metals is one I’ve been working with for several years now (I’ll explain below), and I was astonished to see it carved in the stone of an 18th-century monastery of Mount Lebanon. I won’t attempt a detailed history myself, pointing you instead to The Paradox of the Planetary Metals3 by Yannis Almirantis, but the system had fully taken form by late Antiquity. To quote the author: “The final list of the correspondences between metals and planets, as above, first appeared in a manuscript of a work of Stephanus of Alexandria [Byzantine philosopher, AD 580-640] : Saturn/lead, Jupiter/tin, Mars/iron, Sun/gold, Venus/copper, Mercury/quicksilver, Moon/silver.”

It’s a measure of how mainstream this correspondence used to be, that Chaucer drops it in one of his Canterbury Tales in 1386:

Sol gold is, and Luna silver we thrape,

Mars yren, Mercurie quik-silver we clepe,

Saturnus leed, and Jupiter is tin,

And Venus coper, by my fader kin!

In Europe at least, it dominated till the 16th century, and while the medieval Islamic world (heir to Greek science) had pretty much the same model, this still doesn’t explain my sundial so late in the day. Then again Lebanon is the land of the unlikely.

As for what all this has to do with making art, the answer lies in the use of historical pigments, several of which are metal oxides (not to mention gold and silver leaf) and therefore are also linked to the Spheres4. I personally love to think that the whole solar system is involved in a small way with the mineral side of my painting palette, just like the Earth is present in my plant-based colours.

My encounter with the sundial predated my artistic journey: a confirmation that the end is often found at the beginning…

This is a mountainside, so “below” doesn’t actually mean underground.

The word carved is ردي but I could be mistranslating it. It surprises me a bit but the metal mercury is, after all, quite ruinous to the health.

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 31–42, 2005

To expand on this is best left to another day!

Wonderful that you could even attempt to complete the sundial - such a treasure to unlock. Such a shame these pieces are neglected, lost in time.

Great story, amazing sundial. And the hopscotch grid puzzles me! :D