To start at the beginning, read this first:

Lunar Time

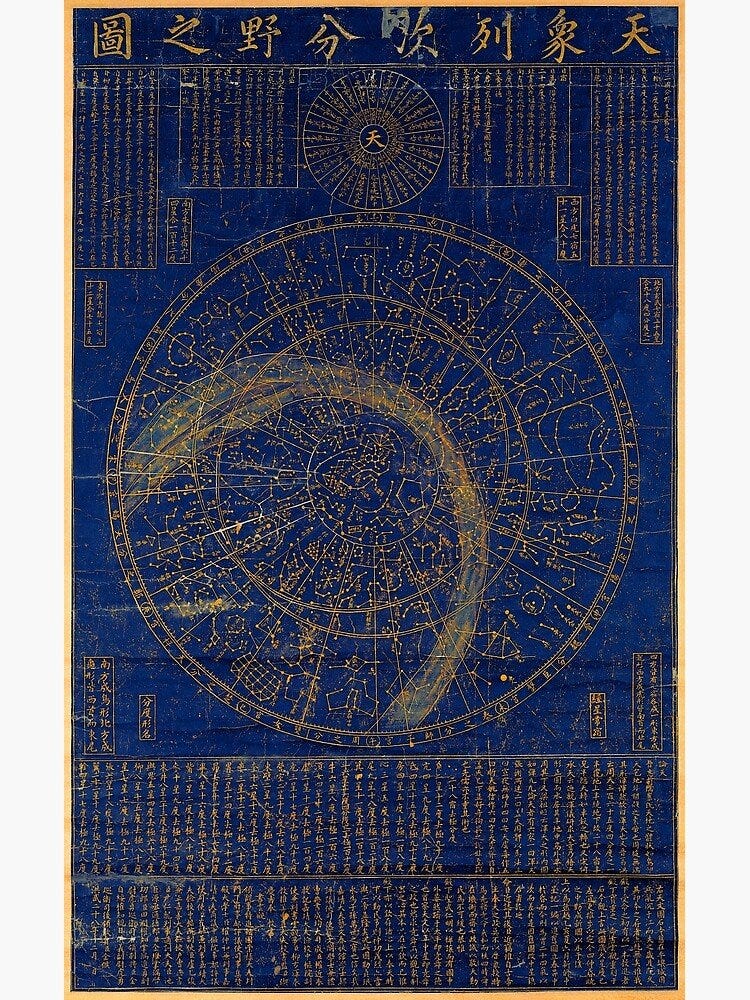

This volume is much shorter, but presented a particular challenge. While I was going through manuscripts, this copy of Cheonsang Yeolcha Bunyajido, a fourteenth-century Korean star map, was brought to my attention:

Having seen it I knew I simply must have this volume entirely on indigo paper. I'd been using indigo as the colour of night, so it was inconceivable not to follow through, though that meant I had to prepare a vat and dye the paper. No small operation, and quite impossible in my college set! But when I had worked out and cut out all the pages and volvelles I needed to dye1, spending a couple of days in London doing that was worth my while.

Working with indigo in a tiny bathroom requires such contortions and carefule handling it’s quite impossible to record the magical moment when the paper emerges yellowish-green from the vat, and turns blue before your eyes. But you get an idea of the work conditions.

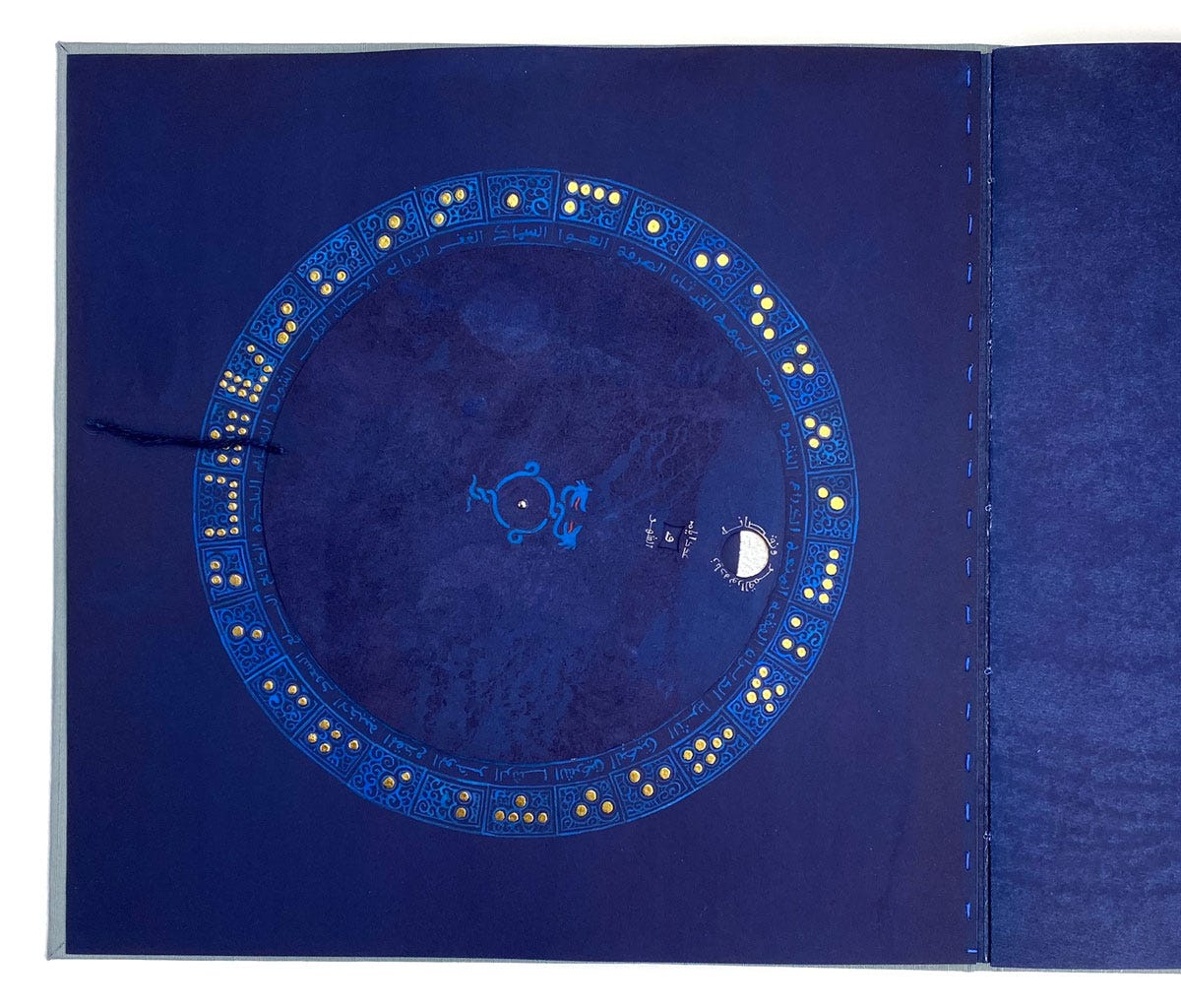

Twenty-Eight Mansions

The "mansions" or "stations" of the Moon, translation of Arabic manāzil (plural of manzil), are the lunar equivalent of the Zodiac signs: the Moon orbiting the Earth defines a belt that is divided into twenty-eight sectors, each associated with a star or an asterism2, so that a manzil lasts about 13 days. Another way of looking at it is that every 13 days, a new manzil rises over the horizon at daybreak.

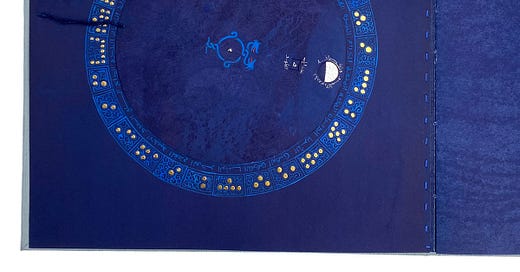

It's important to note that the mansions and moon phases are actually two separate diagrams sharing the same space. They can often be found separately, but combining them was popular. However, there isn't actually a relationship between the different phases and the mansions, as it seems to suggest. It’s the new moon specifically that is observed to move through 28 manāzil during one solar year. That the Moon is shown to have 28 phases (i.e. days) to match the mansions is an artistic convention, but in practice a lunar month has 29 to 30 days (as a lunation or synodic month is 29.53 days).

Another source of inspiration for this page was an astrolabe with an unusual feature: a lunar volvelle on the back. In the small peephole, what you see are numbers marking the days of the lunar month. The New Moon is the final day in the cycle, and day 1 is when the first sliver reappears.

As for the two dragons, they appear frequently in the iconography of the moon, at least in Islamic lands.

The dragons are a symbol for the lunar nodes: the two points at which the Moon's orbit intersects the ecliptic, passing in front of the apparant path of the Sun. In other words these are the areas of space where eclipses can take place: a lunar eclipse happens when the full moon is near a node, a solar eclipse when the new moon is near a node. Eclipse years are still called draconic years today! And because the nodes describes an orbit themselves, with a motion contrary to that of the Sun and the other planets, the nodes3 are sometimes further conceptualised as a pseudoplanet, al-Jawzahr, the Dragon that swallows the Sun or Moon during eclipses.

I feel I should stress that using the symbolic image of a dragon eating the sun doesn’t mean that anyone actually believed a dragon ate the sun. Both in the East and the West, medieval scholars were well aware of what caused eclipses, and routinely calculated the dates and exact position of both total and partial eclipses, including these in almanacs in the form of illustrated tables.

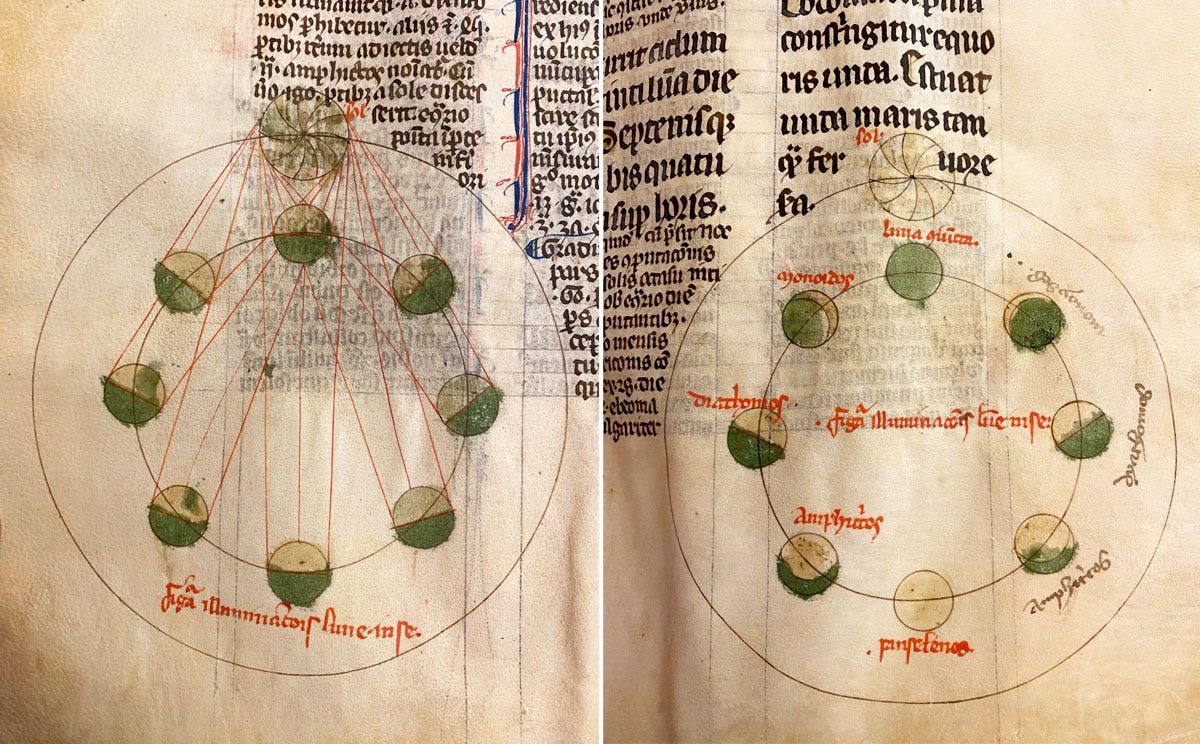

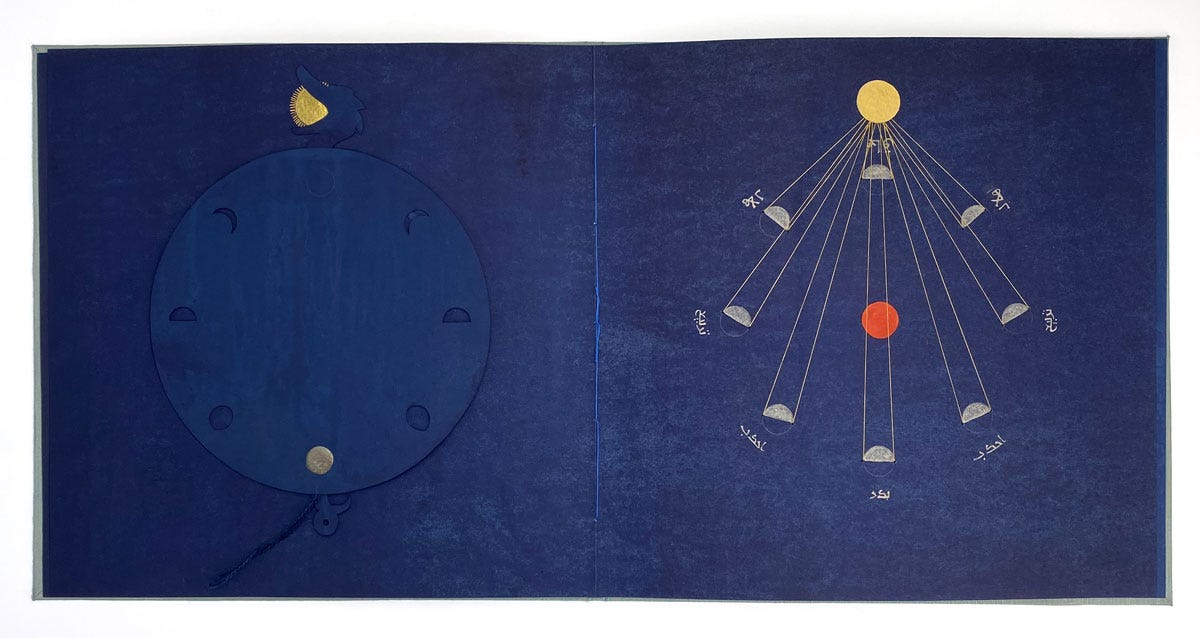

Eight Lunar Phases

On this spread, two facing diagrams both describe the changing aspect of the Moon. On the left, the volvelle rotates to display how we experience it from our earthbound position: Crescent, Quarter, Gibbous and Full Moon, with potential solar eclipses (the dragon swallowing the Sun) around the New Moon. On the right, the same phases as they would be seen by an observer not located on Earth, showing how the rays of the sun (gold thread stretched across the paper) always illuminate half of the lunar sphere, and the latter's position relative to both Sun and Earth determines the phase that we can see. These two pages are based on a pair of medieval diagrams found together in both Eastern and Western texts.

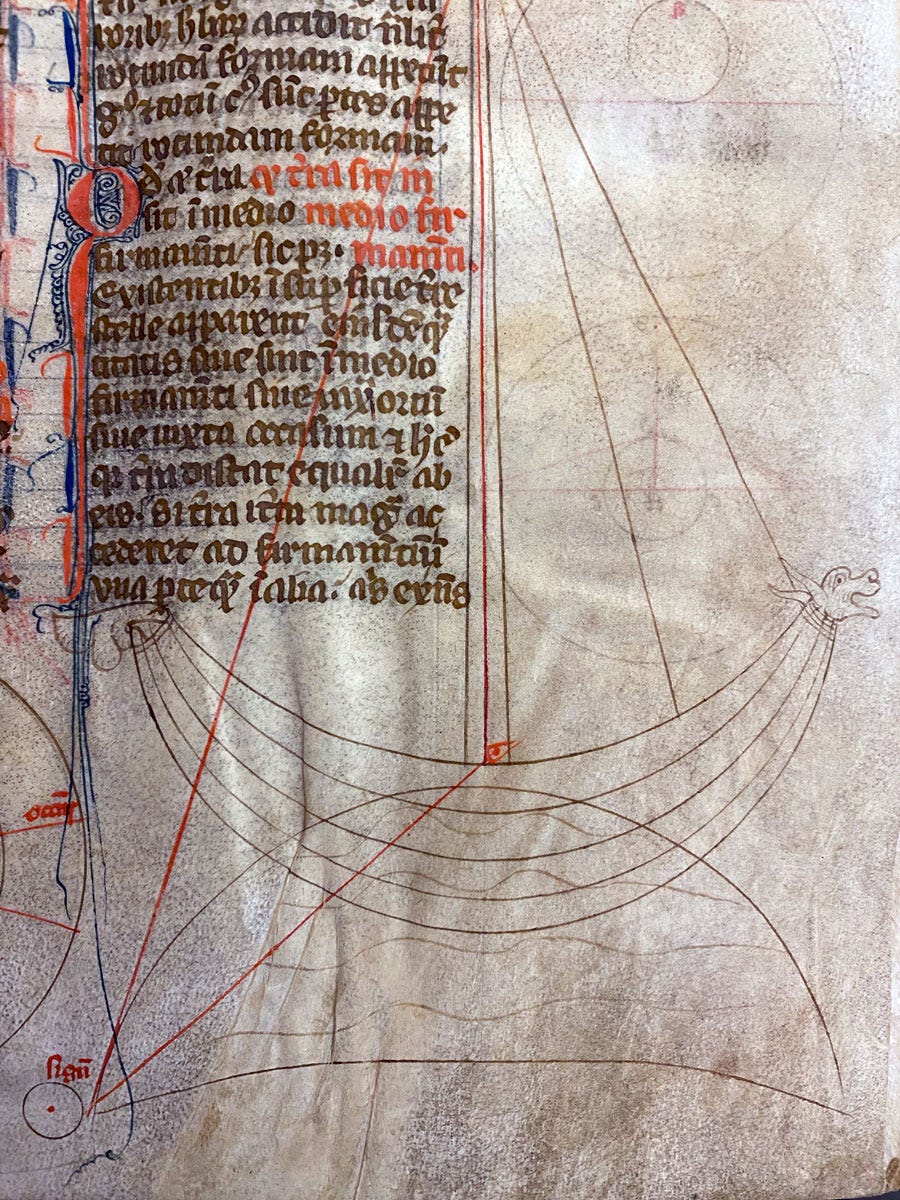

What these diagrams take for granted, but that bears pointing out, is that all the bodies involved are spheres. In fact the same manuscript contains a treatise titled The Sphere, by Johannes de Sacro Bosco, which features this delightful illustration:

This shows a ship on a sea with an exaggerated curvature, and the two red lines (to the top and bottom of the mast) are lines of vision, to explain: When you look out at sea, the curvature of the earth means you see the mast of a ship before the ship itself comes over the horizon. This enviable degree of common sense is inevitable when one's life depends on paying attention to the natural world. I can't help but feel that much of today's denial of reality, that we project onto the Middle Ages, is the result of losing or neglecting the ability to inhabit or even see physical reality as it really is.

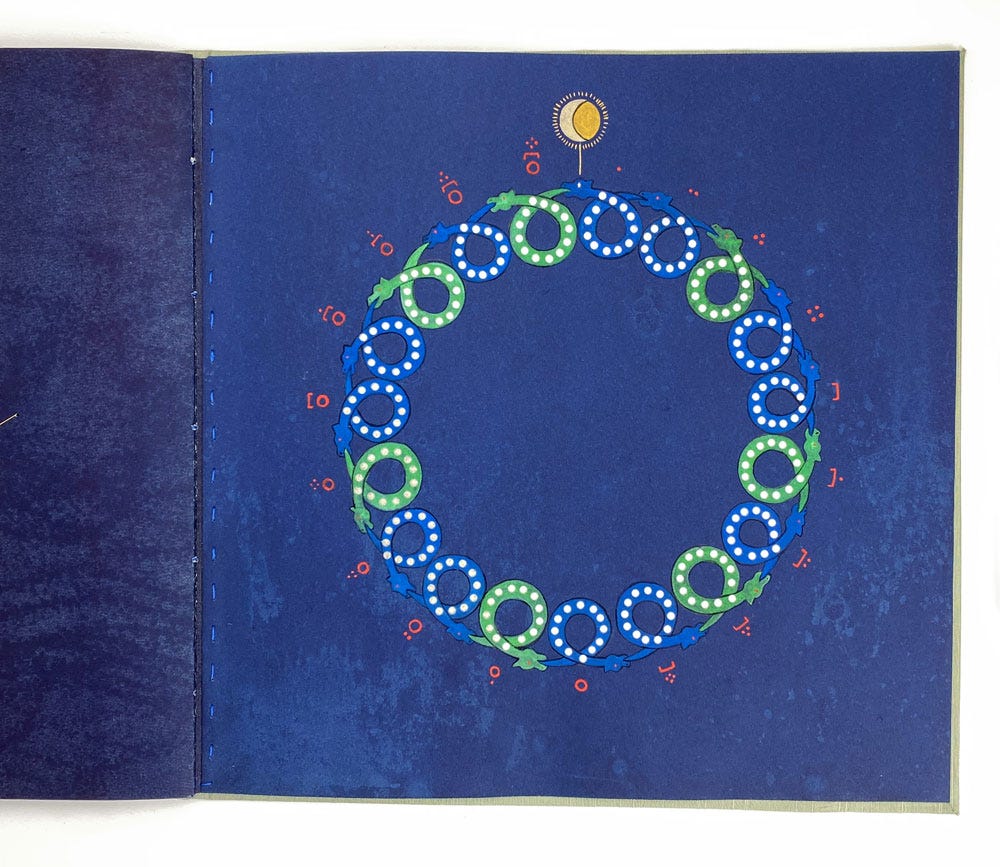

Nineteen Years of the Metonic cycle

This diagram is entirely my own creation, but it attempts to represent a cycle that was once extremely important though it has fallen out of use. The Metonic cycle: a period of almost exactly 19 years after which the lunar phases recur at the same time of the year, and therefore a means of synchronising solar and lunar calendars. In the medieval Christian world, where moveable feasts such as Easter were based on the full moon, the Metonic cycle was indispensable to calculate the dates of such feasts accurately. It made possible the creation of almanacs that functioned as perpetual calendar valid for over 100 years (after which an adjustment was needed to compensate for the slight inaccuracy in the cycle).

One complication is that in a Metonic lunisolar calendar, there are twelve years of twelve lunar months and seven years of thirteen lunar months. In the Babylonian calendar, the long years are years 3, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17 and 19.

I had to really think of how to visualise this as a cycle, using symbols from within this system I’ve been putting together. I went back to the beginning, the image of the snake biting its tail as a symbol for the solar year. Nineteen such snakes are described here, each biting the next snake's tail to describe this much larger continuous wheel. They are numbered in a mode we've already encountered, and punched with full moons representing a month each. The blue snakes are the short months with twelve moons, the green snakes are the long months with thirteen moons. At the top of the page, a union of Sun and Moon represent the return to the start of the cycle after nineteen years.

This completes my account of Lunar Time: in the final installment, we’ll be looking at the planets’ influence on our calendar.

Cutting the pieces before dyeing was essential because cutting them afterwards would create white edges, which I do sometimes want, but not in this case!

Though many of the individual stars involved have given their Arabic names to modern astronomy (e.g. Betelgeuse, Aldebaran), these asterisms do not translate into constellations we can recognise today—with the exception of al-Thurayyā, the Pleiades.

The ascending node is the head of the dragon, the descending node its tail.

Beautiful research, I adore the indigo dyed paper and fine illustrations you have created. I have indigo leaves fermenting away, I still haven't got round to making my dye, maybe this will give me the impetous.

Aha, azurite! I had thought maybe fuchsite, but that would be too green. How very beautiful it is against the indigo. For the third time (each time this series), my perception/experience of the world is expanded by reading about this artwork.

Why did you decide to omit the tongue of the dragon in the lunar phase volvelle?