To start at the beginning, read this first:

Twenty-Four Hours in a Day

Having divided the year into its basic integral components, which are days, we now zoom in to a single solar day with its own divisions: the hours. The page above shows a twofold 24-hour clock. The sun icon at the four cardinal points is now red (a medieval alternative to gold for this luminary) and turns into a moon icon, so the division is now from day-time to night-time with sunrise/sunset in between.

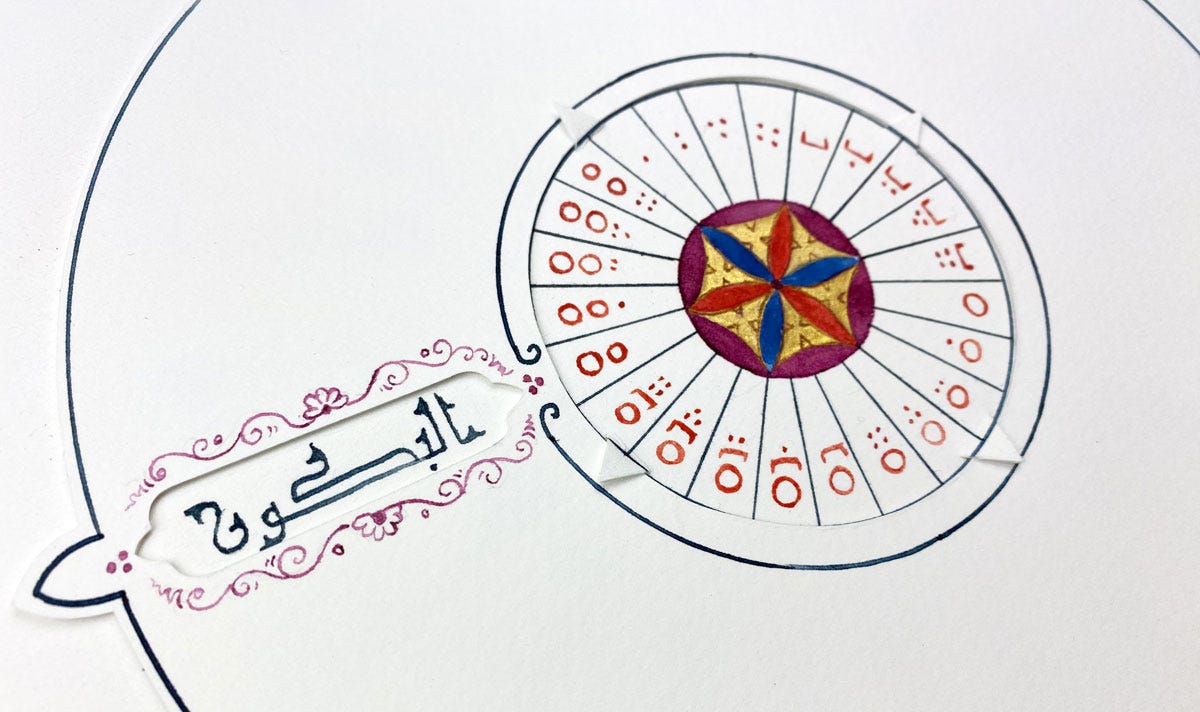

The static clock face at the centre is directly based on the manuscript above (where it’s captioned “hours of the day and night”), together with its peculiar numbering system. Around it are the Arabic names for the 12 hours of day and 12 hours of night.

These names constitute a very old tradition that hasn’t been used in a thousand years, though some of them have entered the language to indicate less precise moments in time, such as "early morning" or "the dark of night". But the full list still reemerges here and there, and I first encountered it on social media, in a post that just claimed “these are the names of the hours in Arabic” with no explanation, context or source, making it difficult to verify. I had wanted to use these names ever since, but not until I was sure they were genuine, and knew something of their origin. It's not until I had access to the Bodleian's resources for this project that I was able to find proper information1, and several variants on that list, so that I can now confidently work with them.

The list I settled on (with adjustments) is the one provided by Hamza al-Isfahāni (10th-century Persian philologist and historian) and al-Tha’ālibi (Persian writer and poet of the same period). At that time, Arabic-speaking scholars2 under the Abbasid caliphate were engaged in a massive effort to systematise knowledge3. In all likelihood, a number of earlier words used to losely refer to different times of the day were then arranged in a systematic list – where extra words may have been added to make it a neat twelve and twelve. Dialectal differences would account for the existence of slightly differing lists.

Day-hours:

Shurūq الشروق

Bukūr البكور

Ghudwa الغدوة

Ḍuḥa الضحى

Hājira الهاجرة

Ẓahīra الظاهرة

Rawāḥ الرواح

‘aṣr العصر

Qaṣr القصر

Aṣīl الأصيل

‘ashī العشي

Ghurūb الغروب

Night-hours:

Shafaq الشفق

Ghasaq الغسق

‘atama العتمة

Sudfa السدفة

Jahma الجهمة

Zalla الزلّة

Zulfa الزلفة

Buhra البهرة

Saḥar السحر

Fajr الفجر

Ṣubḥ الصبح

Ṣabāḥ الصباح

Variable Day, Variable Hours

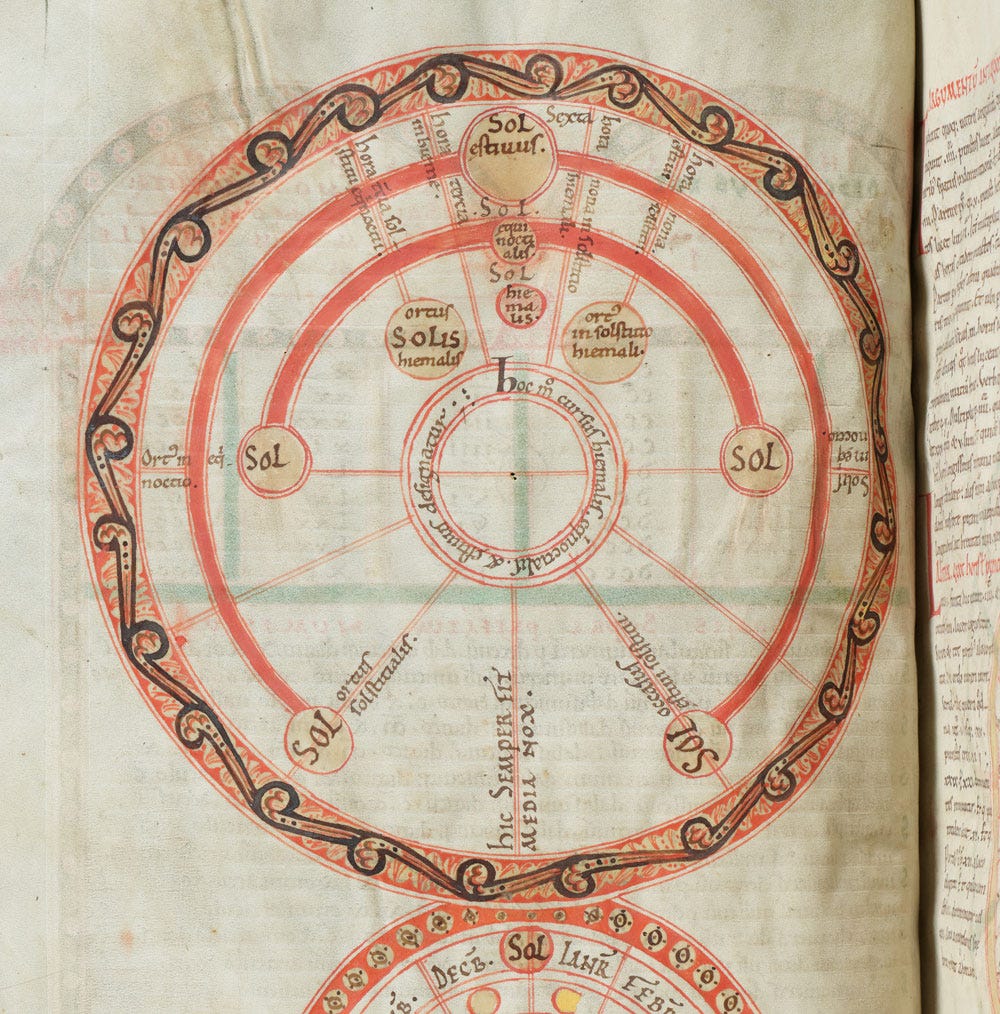

The volvelle that makes up this page is based on a diagram that seems to have been well-known in medieval times, as I came across it in several places. This is a beautiful and rather sophisticated conceptualisation of the path of the Sun at the solstices and equinoxes. It depicts both the changing length of daylight and the changing place of sunrise through the year. Of course it’s only accurate for a certain latitude, but it conveys this notion in a simplified way that’s valid for Northwest Europe.

At the Winter Solstice, the sun (lowest arc) rises in the South-East, passes low across the sky, and sets in the South West. The day is very short.

At the Equinoxes (middle arc) the sun rises in the East and sets in the West, reaching an intermediate height and creating a day of intermediate length.

At the Summer Solstice the sun rises in the North East, passes high in the sky and sets late in the North West. The day is very long.

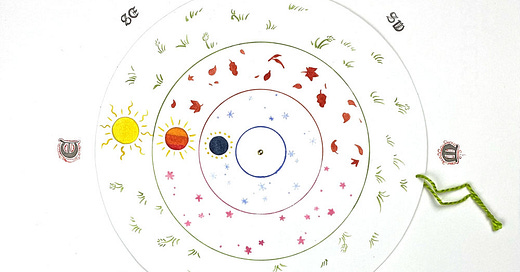

I adapted this into a volvelle so we could see the sun’s movement, enhanced by clues indicating the seasons and the sun's strength. Yellow indicates day and indigo night, with a colourful transition when the sun rises or sets. In essence, it's a comparative animation of daylight at the height of each season, where you can directly see how the winter day lags behind the summer day, and so on.4

What should also strike the observer, is that this is the configuration on which clocks were designed. If you look at the 24-hour dial of early clocks, the small hand is showing you where, on the diagram above, the Sun is positioned at that exact moment. Or to put it visually:

This final page in the Solar Time volume is the previous diagram in a more abstract form: translated into hours. Today our hours are all the same length: this is the middle circle, which corresponds to the clocks and watches we know. But in the past the hours were variable. The day was divided into 12 equal hours and the night into 12 equal hours, independently of each other; in summer, day hours were long and night hours were short, and vice versa in winter. It’s only at the equinoxes that all 24 hours are equal. With this dial we can see this in operation, and note that for instance, the first hour of day in summer is the ninth hour of night in winter.

The Arabic numerals I used look a little different from what we’re used to, as they follow the form used in the medieval manuscripts I looked at — and also on one of Merton College's own astrolabes, which I had the opportunity to examine closely:

This completes my account of Solar Time; the next installment will be about Lunar Time.

If you’re curious and want the whole discussion about these, you’ll find it in: David A. King’s In synchrony with the heavens: Studies in astronomical timekeeping and instrumentation in medieval islamic civilization (2003 edition), volume 1, chapter 8: On the Origin of the Names of the Prayers.

This is more correct than to say “Muslim scholars”, because the Abbasid court welcomed and employed great minds and skilled scientists from among all the “People of the Book”. Famous examples are the Bukhtishu family, a lineage of Assyrian Christians who were physicians at the court of the Caliph for a period that spanned the seventh to ninth centuries. Another is Thābit bin Qurra, the ninth-century physician, translator and astronomer at the court, who was a Sabian from Harrān; the little that is known about this religion is that it consisted of planet-worship. There are reasons why the Sabians were accepted rather than persectued as outright pagans, but this isn’t the place for that story.

Frankly the whole thing was OTT, simultaneously priceless for future generations, and disastrous in that whatever felt messy was rationalised or rewritten, so that traces of earlier traditions were trampled over. I know this from the nonsense that was written at that time about the birth of the Arabic script, for instance, and the ahistorical myths that stubbornly continue to come down from that revered period and dominate education in the Arab world. Every age of genius has its shadow.

This model could easily be adapted to visualise the length of daylight at other latitudes. All you need is the times of sunrise and sunset for the longest and shortest days, and adapt accordingly…

Fascinating. I enjoyed the challenge of envisioning my geographical point of reference to the North in order to feel that volvelle, not just look at it. Reading this post I think changed my experience of clock-time; twenty-four hours of the same duration, all year, now feels abstract. As if it is disciplining, even subverting that "messy" and "unsystematized" knowledge that emerges from embodied/relational/communal experience of the world. As we head into summer at my latitude, I am going to be paying attention to whether the hours feel as if they are lengthening ....