Among the Kufi scripts I’m constantly investigating is the so-called Square Kufic, born of brickwork wall-decorating techniques sometime in the 12th century. It’s one of the scripts I teach, and I’m always telling students to study historical examples to internalise the rules of the script, but it’s (very) difficult to find clear pictures with no restrictions attached. So I started redrawing examples for my classes, with notes. I lack the ability to do things partially, so this soon turned into the first sallies into a massive survey of these inscriptions, in their architectural context, with perhaps a book at the end of the journey. Or as I like to think of it, intensive apprenticeship, because recreating the work of past masters (and poor attempts) is turning out to be immensely instructive.

I’m sharing some of this work as I go along because I think you’ll find this sacred art as wonderful as I do.

(I realise not every subscriber is marinating in Islamic art and Arabic calligraphy as I am, so please don’t hesitate to ask if something I take for granted isn’t clear to you. There are no silly questions.)

Square Kufic flourished in central Asia and Iran until the 15th or so, after which it started going into visible decline. Meanwhile designs copied on paper made their way West to the Levant, Egypt and Turkey, which was well and good except it doesn’t seem any actual trained designers made the trip, and the output in those regions never reached a standard worth talking about (except as a warning to the complacent).

Inscriptions in Square Kufic were not made for reading. If this wasn’t obvious from the extreme stylisation of the script, it would be gathered from the placement of inscriptions within a building: small medallions too high up to make out with the naked eye, huge spiralling inscriptions on walls or even ceilings that would require unlikely contorsions to decipher, friezes that run around large spaces. Their purpose is simply to be there, so the power of the Word can suffuse and define a sacred space, the way sacred symbols would do in other cultures. It’s nothing to do with literacy, but the ability to see text as an image as opposed to reading text as a vehicle of information. Today, people no longer have this ability – or to be more accurate, the conditioning to read text is so overwhelming that a conscious effort is required in order to just see it. This doesn’t operate when you’re looking at a script foreign to you, but Arabic speakers, whether faced with an old inscription or a contemporary piece of calligraphic art, have by now been educated out of the core contemplative feature of their native art form.

Anyway, that’s enough of a tangent. Though Square Kufic was not meant to be read, uncovering what these walls have been whispering for centuries to all who enter is precisely what I’ve set out to do.

(All images are ©Joumana Medlej unless otherwise specified. Please don’t repost them, seeing my diagrams pop up on Pinterest would really make me rethink sharing so much for free.)

My first stop is the Great Mosque in Isfahan, the north iwan1 to be precise.

Here’s my diagram on which I’m mapping every bit of text that can be found in this part of the mosque.

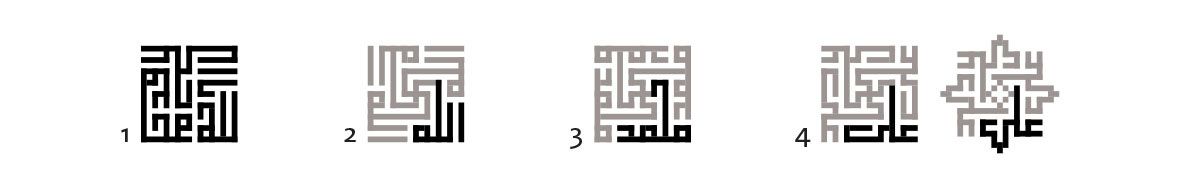

It’s still incomplete: I haven’t even highlighted or finished studying all the inscriptions it features. I figured this was enough to begin with. Here are close-ups of 1 to 9, with their transcription and translation.

اللّه محمّد علي God, Muhammad, Ali

اللّه God

محمّد Muhammad

علي Ali

يا قاضي الحاجات O Judge of needs

سبحان الله والحمد لله ولا اله الا الله والله اكبر Glory be to God; praise be to God; there is no deity but God; God is the greatest.

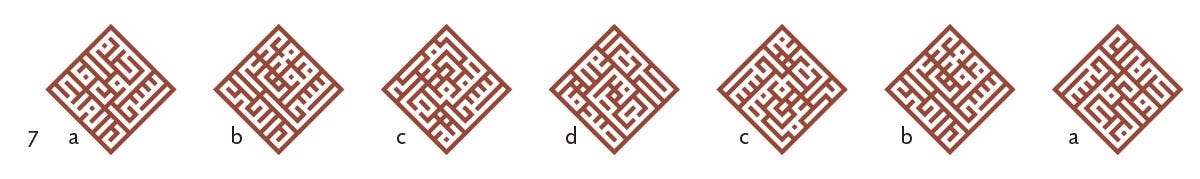

7 is a series of medallions spread along a band inside the arch:

a. سبحان (ذي) المُلك والملكوت Praise the Lord of the Visible and Invisible

b. سبحانه الحي الذي لا يموت Glory be to Him the Living One who never dies

c. سبحانه تعالى عمّا تصفون Glory be to Him who is beyond all you can describe

d. صدق الله العلي العظيم God Most Great has spoken the truth

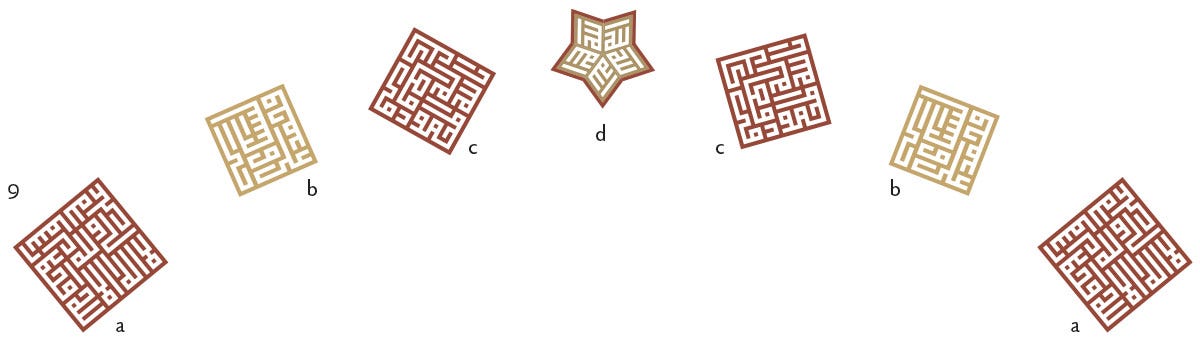

In these four pairs of identical eight-pointed stars we find again God and the rotated names Ali and Muhammad, then in gold:

سبحان الله والحمد لله ولا اله الا الله والله اكبر Glory be to God; praise be to God; there is no deity but God; God is the greatest.

Finally on the far wall, an arch arrangement of more medallions:

a. لا اله الا الله محمد رسول الله علي ولي الله There is no deity but God, Muhammad is God’s messenger, Ali is God’s friend/saint.

b. محمد وعلي خير البشر Muhammad and Ali are the best of humanity

c. يا الله المحمود في كل افعاله O God praised in all His deeds.

d. A five-fold الله

There we have it, a fraction of what this particular sacred place has to offer…

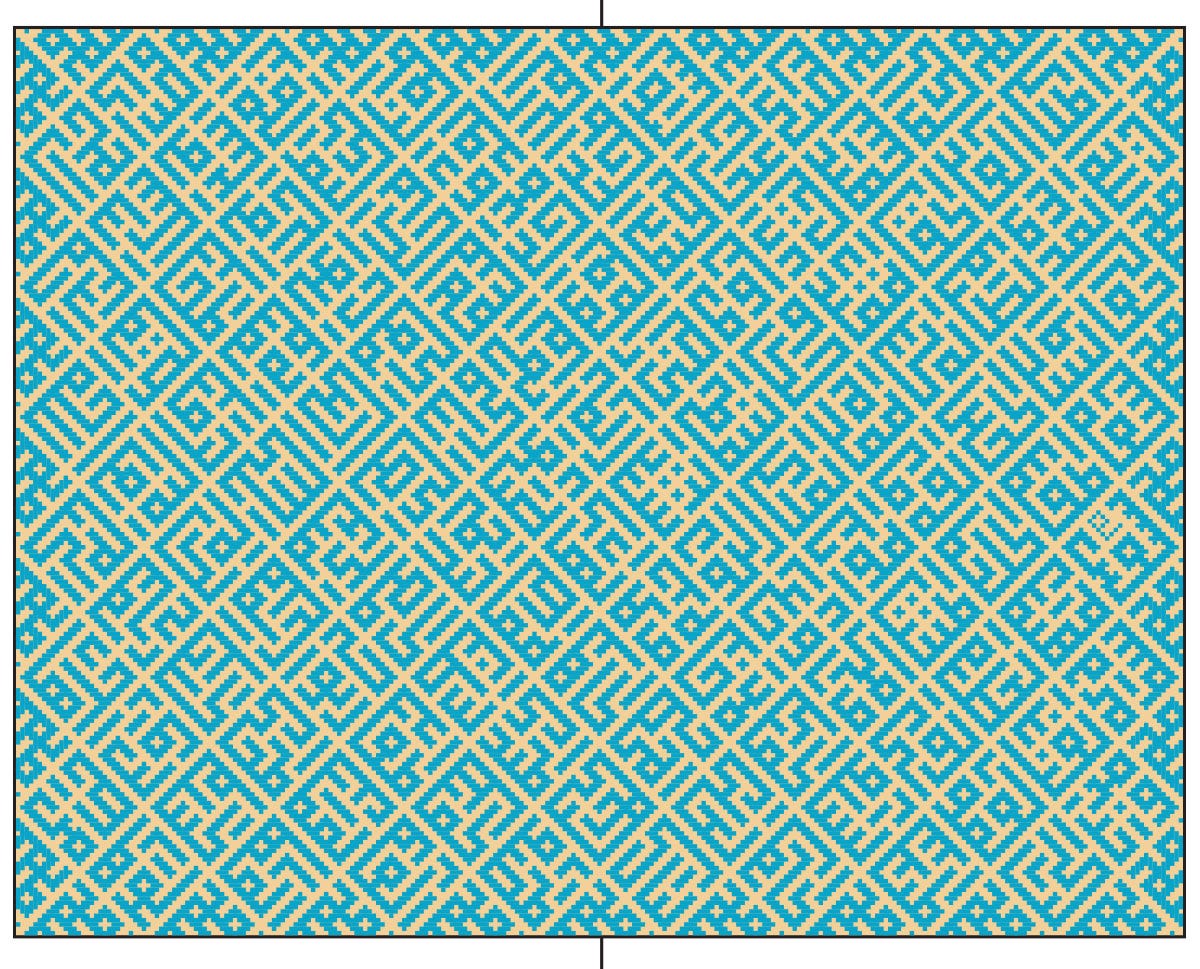

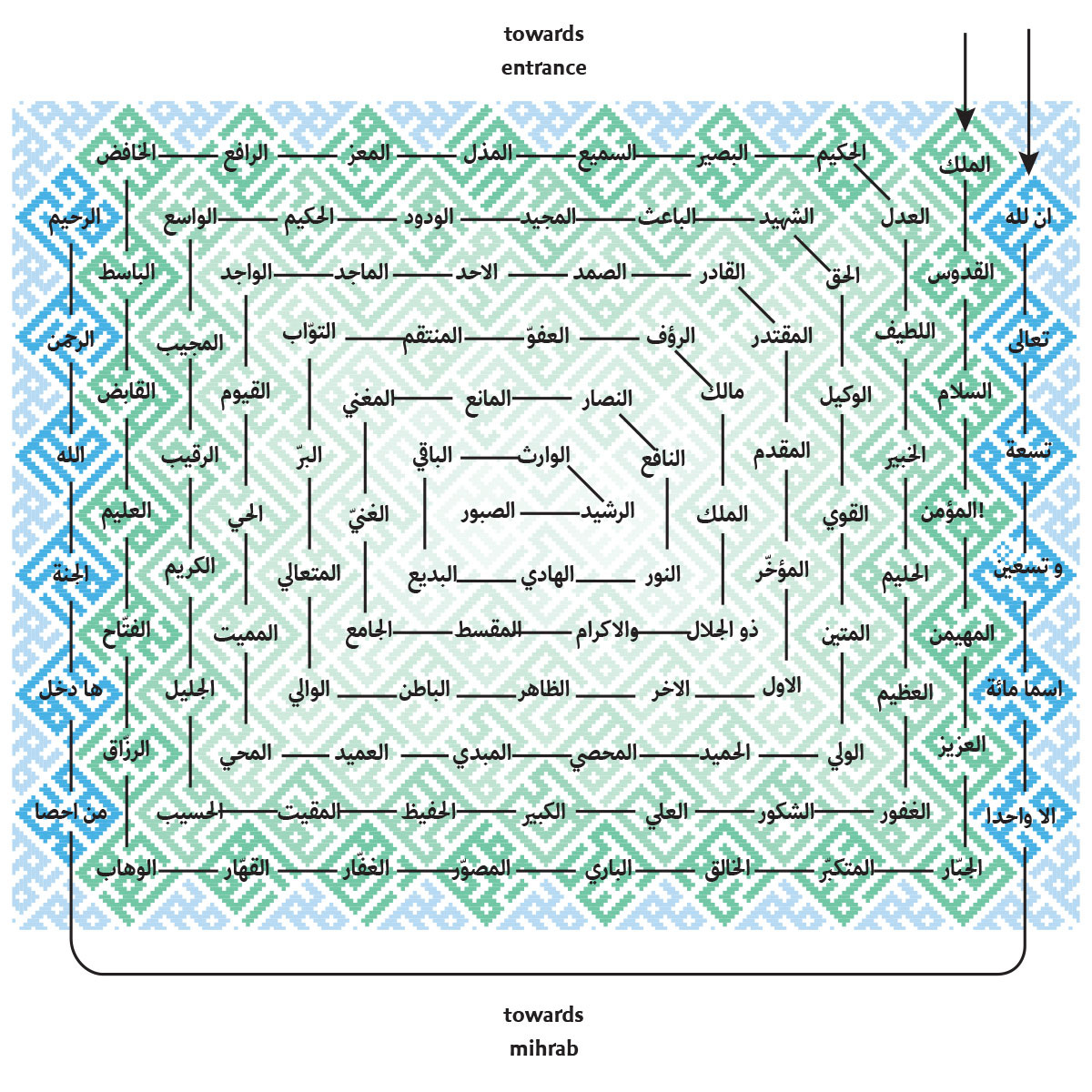

The Great Mosque in Yazd is equally rich and will occupy me for a while, but today I wanted to pull out this remarkable design, from the arch leading to the mihrab2.

If you stood under that arch, facing the mihrab, and looked up, this is what you would see:

The text consists of the Ninety-Nine Names, preceded by the hadith3:

إن لله تعالى تِسْعَةً وتِسْعِينَ اسْمًا مِائَةً إلا واحدا مَنْ أَحْصَاهَا دخل الجنة

"Verily, God has ninety-nine names, one-hundred minus one. Whoever memorizes them all will enter Paradise."

This framing hadith is also literally framing the names, starting at the upper right corner then continuing from the bottom left. The list of names itself then starts in the same corner and spirals inward clockwise. The provisional diagram below isn’t very pretty and I couldn't include translations but you’ll find them here). The repeating motif all around the composition is the name Muhammad.

It's an astonishing feat of composition, even though the individual names are far from perfect. Some can be fixed by moving a couple of tiles, so that can be down to tilesetter misreading the design, but many of the names are highly contrived, withletters missing or totally distorted. There's no other way, it's not actually possible to gracefully force all the names into squares of the same size without some violence to the rules of the script (there have been many attempts, even contemporary). But it's mind-boggling enough that they managed to create such a precise composition to fit the available space.

That’s me done for today; if you enjoy this kind of contents do let me know in a comment!

Iwan: a typical Iranian architecural feature going back to Mesopotamian times, a vaulted hall completely open at one end.

Mihrab: a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the direction of the Kaaba, thus helping to orient oneself for prayer.

Hadith: A saying of the Prophet Muhammad that is not part of the Qur’an but has been recorded and transmitted down.

This is such valuable scholarship, research, sleuthing and draughts-womanship. Brava. I learn so much reading your work. Good Yule, Joumana!

Hello again Joumana. I saw your message on my screen - and then it disappeared!! I can’t find it and wonder if you could send it to my email:

white.lynn09@me.com I’m sorry to trouble you, and thank you. Best wishes, Lynn Watson