Timekeepers

Human keys to heavenly motions

Greetings from Merton College, Oxford, where I’m happily ensconsed in a research-based Book Arts project. My topic is Time – timekeeping, systems of time, time theories, and so on, and for this purpose I’m examining, and drawing inspiration from, a remarkable array of tools and methods humans devised to keep track of the positions of luminaries, planets and stars. I’m mostly focused on the medieval period, and it’s impossible to learn about all this and still have any patience for the expression “dark ages”1. If a society’s general level is judged in terms of making the most from information available to it, I rather think we are the ones stumbling about in a dark age, capable of the most wilful ignorance despite the highest levels of literacy and schooling2.

Anyway, since I’m swimming in dazzling new knowledge, I thought I would share some of what I’ve been discovering, and today this would be a few noteworthy objects from the History of Science Museum.

The Museum is a completely enthralling place. Not only is it the oldest surviving public museum building (built 1683), it houses the most astonishing collections of early scientific instruments (especially mathematical and astronomical) from Europe and the Middle East. It really is a must visit, and it’s free! I stumbled upon it by chance the first time I visited Oxford, and the collection of Islamic astrolabes floored me, to the extent I spent all my time examining them and neglecting the rest. Now I’m looking more closely, and here are a few objects that particularly caught my eye.

Photos are mine. The caption for each object has its inventory number and a link to its homepage, where there are more photos and details.

Astrolabe, by Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Battuti, North African, 1733/4

I have to show at least one astrolabe, considering their importance and the elegance of their design. This one was given as a bequest to the minaret of a mosque in Fez, probably for the purpose of calculating the hours of prayer. Though obscured in the photo, it includes lines marked فجر (for the dawn prayer; you can just see this word on the left just under the horizontal bar), ظهر (midday) and مغرب (sunset). But an astrolabe is a flattened model of the heavens, and has many other functions – star chart, inclinometer, measure altitude, or latitude, etc – in fact the tenth-century astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi described more than 1,000 applications for it. It was the supercomputer of the time, and just as portable.

Astrolabe and Astrological Volvelle, Italian, Later 15th Century

A volvelle is a wheel chart, that can be made of metal but is often found inside books made in paper or parchment, with rotating parts. The astrolabe is on the front of this object, but the photo shows the astrological volvelle on the back, which is highly unusual with its many pointers:

The engraved fixed scales comprise abbreviated names of the heavenly houses [life, wealth, brothers, etc], a solar calendar, the zodiac (0° Aries = c.16 March; concentric type), its decanates and their rulers, and symbols of the elements (fire, air, water and earth) attributed to the several signs and quarters of the zodiac. The lowest movable disc carries eight pointers which were used to determine the principal astrological aspects. The eight upper pointers which are attached to individual movable discs served to mark the position of the seven planets and of the nodes (caput and cauda draconis) of the moon. The next scale gives the exaltations of the planets where each classical planet is allocated to a zodiac sign and given the degree of its exaltation.

Astrolabe and Equatorium, Southern France or Northern Italy, Late 15th Century

An equatorium is used to determine the positions of the planets. It complements the astrolabe, which only involves the daily rotation of the Sun and stars. We see here the equatorium side, with its three-lobed disc. Each lobe carries a planetary disc and pointer.3

Astronomical Compendium, by V.C., English, c. 1554

This exciting object is like a tiny brass almanack; an astronomical Swiss knife, if you will. It incorporates a sundial and moon dial, a nocturnal (to tell the time at night by the movement of the stars), a compass, an inclinometer, a nautical square, star-maps, a lunar volvelle, tables of latitudes and tides. It’s so portable it can be worn around the neck on a chain, which irresistibly reminds me of my Book of the Moon.

Perpetual Calendar and Sundial, English, c. 1792

The compass is inside the box, but the wooden box itself is working hard: the paper covering it is printed with, on top: tables of feast-days, a perpetual calendar and a table of dominical letters4; around the side, a table to determine the time in various places. Even the bottom has tables for “the hours of sunrise and sunset, the dates when the sun enters the various divisions of the Zodiac, the moon's age, phases, and southing, etc.” I’ll add that the tables are printed from engraving plates, but coloured by hand before the whole was lacquered, hence the paper’s longevity.

Azimuth Dial, German, 16th Century

An azimuth (rom Arabic السموت) is the horizontal angle from a reference point, e.g. the azimuth from due North to due East is 90º.5 The gnomon is the part of a sundial that casts a shadow, and this ring-shaped one is quite unusual. In order to read the time, the gnomon is first slid “so that its pointers indicate either the date or the sun's position in the zodiac”. The ring is then rotated to the direction of the sun, resulting in the southern pointer showing the time. The hour lines are incised in the stone tablet, and the length of the day throughout the year is also indicated. All this adjustment is made necessary by the fact the sundial is portable: if it was fixed, the gnomon would be positioned in the way required by that specific location.

With all that, this is not a universal instrument; it was constructed for a specific latitude. Latitudes are the virtual circles around the Earth, parallel to the equator: since this was made for Germany (though without knowing where in Germany, this isn’t as specific as it should ideally be), it would be equally accurate in, say, Mongolia, but quite off in Spain.

Astronomical Compendium, by Ulrich Schniep, Munich, 1553

Another of these lovely multi-use objects, it includes a nocturnal, a volvelle giving the times of sunrise and sunset, a lunar volvelle, an inclining dial, a compass and a table of latitudes. It was made by Ulrich Schniep, one of the major instrument makers in later 16th-century Munich. The precision required for functional tools of this sort made them extremely difficult to craft; only the highest craftmanship could achieve it, and it’s only fitting that the makers would both embellish and sign their creations.

Diptych Dial, by Joseph Tucher, Nuremberg, Early 17th Century

Portable sundials made up of two leaves that open at 90º are called “dyptich dials”, and like all dials that are not fixed, they need to be oriented very accurately – so a small compass is always integrated in the device. Nuremberg was famous for its ivory dials6 like this one, which also has a suspension ring. A pin would be inserted in the vertical face to serve as gnomon to give zodiac sign, length of day, Italian hours7 and Babylonian hours8; the smaller dials are for Italian hours.

The Tucher family specialised in ivory diptych dials, which were made by various members from the 1550s to the 1640s.

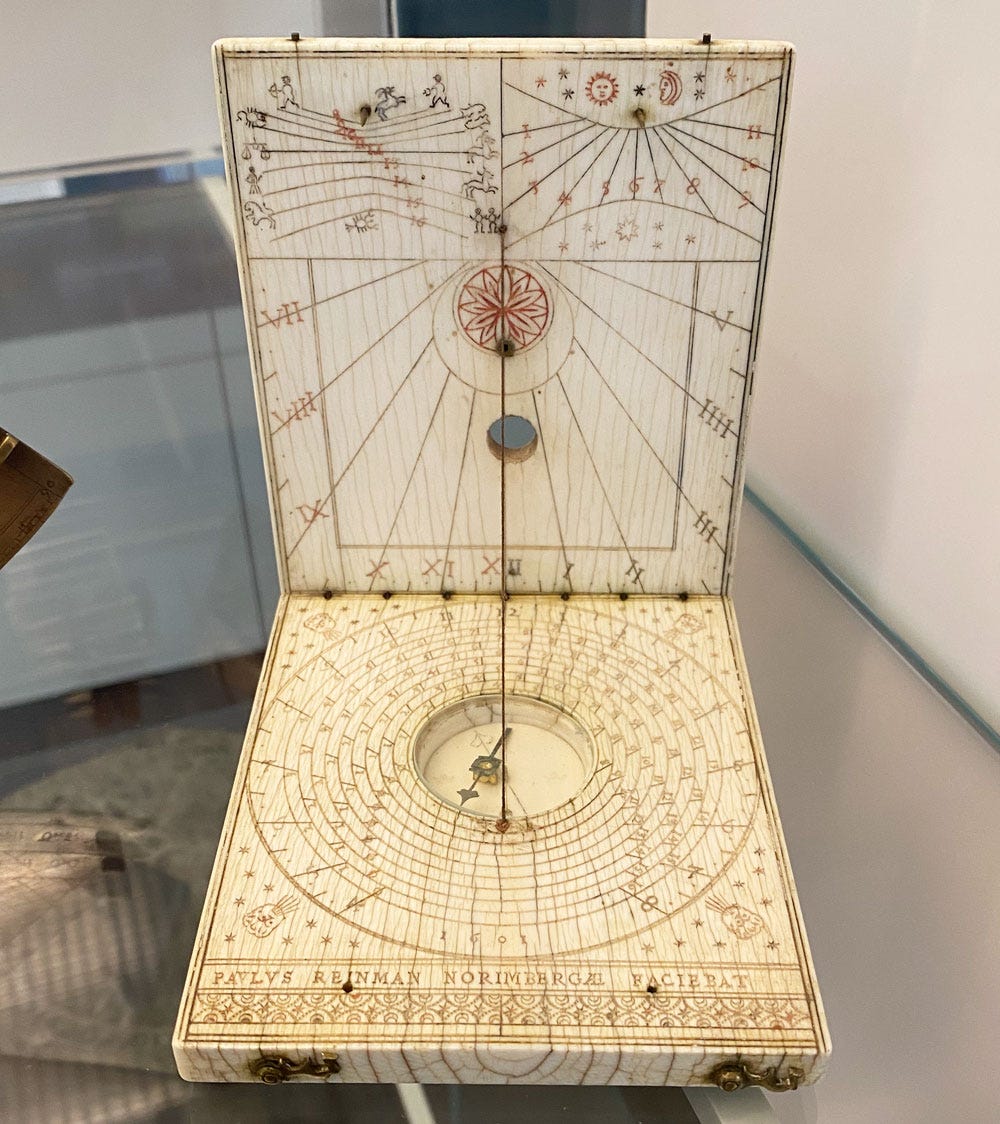

Diptych Dial, by Paul Reinmann, Nuremberg, 1601

Here we see two pin gnomon dials at the top: the one on the left marks the length of the day, the one on the right the unequal hours. The string serves as gnomon both for the vertical dial that occupies the rest of that leaf (for common hours, the 2x12 hour system, with lines for half hours and dots for quarter hours) and for the horizontal one on the lower leaf. The nine circles on the latter are to indicate the hours throughout the year.

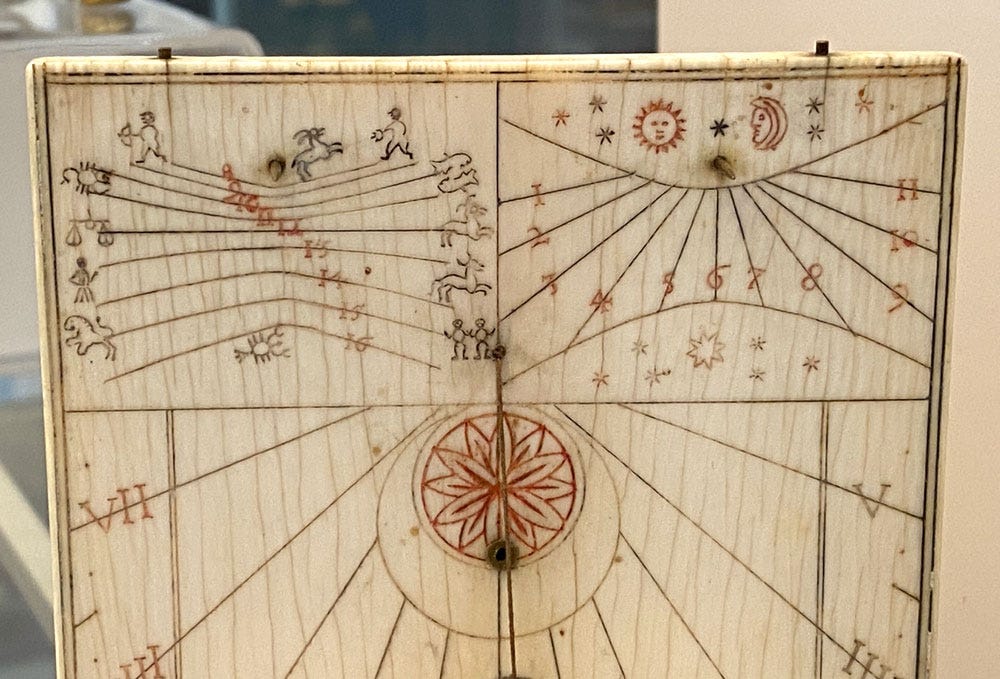

In this close-up you can see the blowing putti, symbolising the winds, that are often seen on Reinmann’s dials. The motif of half moon and stars on the borders is characteristic of his work.

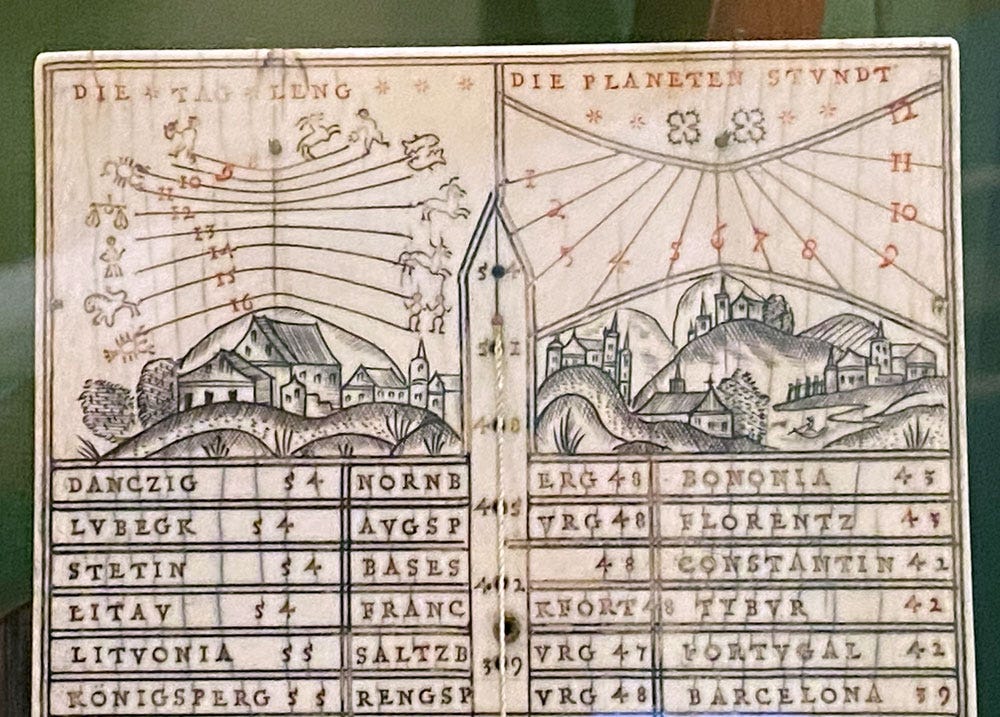

You may have noticed both ivory dials above have something in common: the incredibly tiny and adorable icons for the zodiac signs, which are perfectly identical. This is because they were punched, and it’s clear all the Nuremberg dial makers used identical sets of punches! You can also see them on the detail below, from another of Paul Reinmann’s dials. The city depictions below the dials are exquisite!

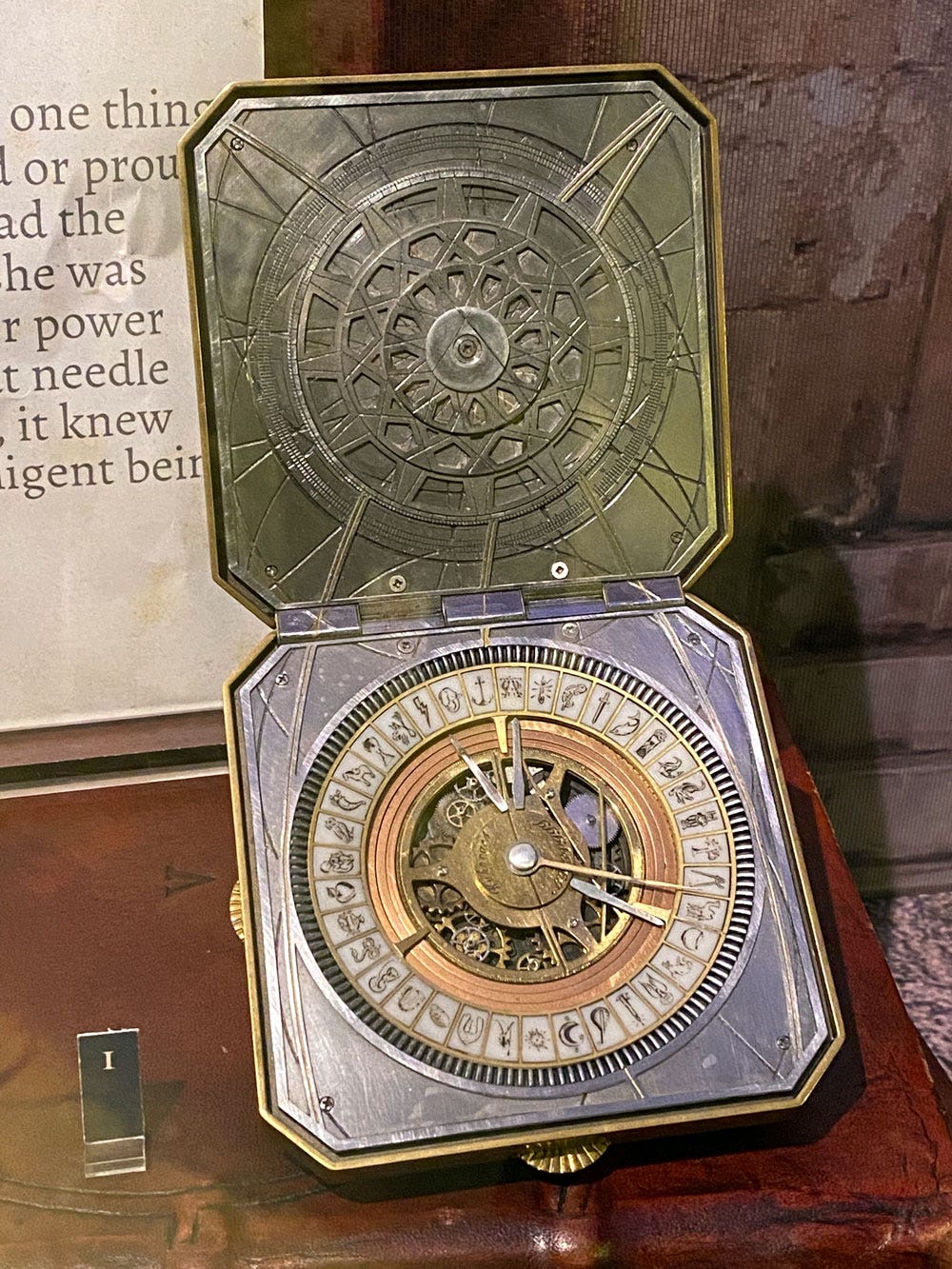

One more object on display deserves to be shared here, though it was never actually used by anyone anywhere, because it was entirely inspired by the wondrous contents of the Museum: Lyra’s alethiometer, the golden compass of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy.

In fact I recommend Seb Falk’s book The Light Ages for a one-stop, engrossing summation of the medieval science of timekeeping, which was inseparable from astronomy (and lots of maths). It made my head spin and bears some responsibility in my temporarily enjoying the life of an Oxford don.

Honesty compels me to add that when I put this to a philosopher of science (such is the company I keep here), he gently questioned my generalisation. But still, there is no condescension towards the state of medieval knowledge in this house.

The object description tells us that metal equatoria are incredibly rare, and that among the few known, there is one on the back of an astrolabe in Merton College. I have a date with this astrolabe coming up, and if I can wrap my mind around any of its functions I will report subsequently.

I will explain these in more detail in a future post detailed John Somer’s Kalendarium, but in brief: For each year, the first 7 days are assigned letters (Jan 1=A, Jan 2=B) in a cycle until the end of the year. If Jan 1 is a Monday, you can glance at the entire calendar and every instance of A is a Monday for that year. The Dominical Letter is whichever letter indicates Sunday for a given year (in our example that would be G). In a medieval hand-written calendar the Dominical Letter would be written in red. In a very real sense, the entire, exquisitely complicated systems that were devised to know the date and time, both in the Christian and Muslim worlds, arose out of the need to worship on schedule.

I hope! 😂 I’m still getting to grips with all this, should have taken an Astronomy 101 course.

I’ve just taken out a fascinating book about them: The ivory sundials of Nuremberg 1500-1700 by Penelope Gouk.

A system whereby the first hour starts with the Angelus (sunset) bell and the hours are numbered from 1 to 24.

System that divides the day and night into 24 equal hours, which is actually not at all Babylonian.

J'adore:::::::::♡

As a one-time land surveyor, I'm in awe of these devices. I remember the tedium of making sun shots (azimuth by altitude) observations in Oman and calculating them by hand using tables. We eventually moved to using a programmable hand calculator that seemed like magic! These must have had the same effect on laymen.