This post is adapted from a recent and rather interminable twitter thread I made, which went viral to the point I found myself my discussing the topic live on Radio New Zealand yesterday.

When I was working on Wild Inks & Paints1, I researched every source of colour that could be foraged or easily procured, got hold of it and tested it in my kitchen lab. Plants that lived up to the sometimes flimsy claims were tested further until I judged them worth sharing in the book.

Cornflower (Centaurea cyanus) was not a flower I was able to locate in the field at the time—I should specify that most of the work was done under the 2020-2021 lockdowns and then ongoing Covid restrictions. I could only travel on foot (and it’s extraordinary that I could find nearly all of these plants growing within 4 km of home), or order dried dyestuffs. Fortunately, many flowers give really good results after they have been dried. I had come across the claim that blue ink was made from cornflower petals, but this was never accompanied by visual proof, so I ordered dried cornflowers. They still looked blue enough, but what they yielded was so underwhelming that I dismissed this species entirely and moved on. At any given time I had four or five plants undergoing a battery of tests, so I had no time to spare for any that failed the most basic one.

That was that for cornflower, until a month or so ago, when this claim turned up again on my timeline. Venetia Jane takes beautiful photos of flowers and posts them along with well-researched lore, but when she repeated the idea that “Cornflower petals mixed with alum water produce a blue ink that can be used as watercolour paint”, I had to ask if she had tried it herself because in my experience that was simply not true, and even the best herbals tended to repeat other authors on trust, without practical verification. We had a conversation about this that left us both wondering about the origins of this “myth”. And at the back of my mind, was the niggling doubt that maybe using fresh flowers would make a significant difference? Nothing I could do about that, though…

Well, life was about to once more demonstrate that if I was curious about a plant, I would be taken to the plant. Shortly after the above conversation, in late June, I took a few days off and went to stay in a little B&B in Abergavenny. And there across the road from my little cabin, was a truly tiny but lovely patch of wildflowers, with the bluest cornflowers I have ever seen. In fact they were the first I had ever seen. They were also the only ones I saw anywhere in or around the town during my stay.

I can take a hint. I collected some of them over the next couple of days, putting them in water, and then brought them home with their stems wrapped in wet tissues so I could work with them at their freshest.

Since I first wrote my book, I’ve become much more experienced with delicate flower colours, so I went straight for the method that gives the best results: braying with alum and only a little water.

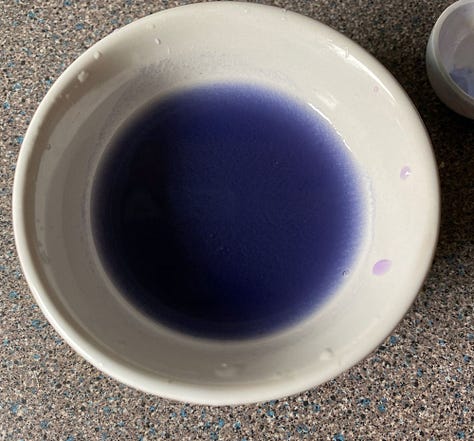

The dye that issued from the flowers was more purple than blue, due to the acidity of alum modifying the biochrome. Cornflower contains protocyanin, an anthocyanin, but here it’s bound with a flavone (yellow) and other constituents in a complex copigmentation relationship. The colour of the dye as a liquid in the pan means nothing, however, until it’s been tested on paper.

As another illustration of how non-indicative this stage is, I inspissated this (reduced till syrupy or dry) in an accelerated way—the less time the biochrome spends in water, the better it’s preserved. But the result of quickening this process was that it dried in this completely mad shade of hot pink.

This incredible colour turns purple again the moment it’s picked up with a wet brush, but also does so on its own over time if the pan is left alone2.

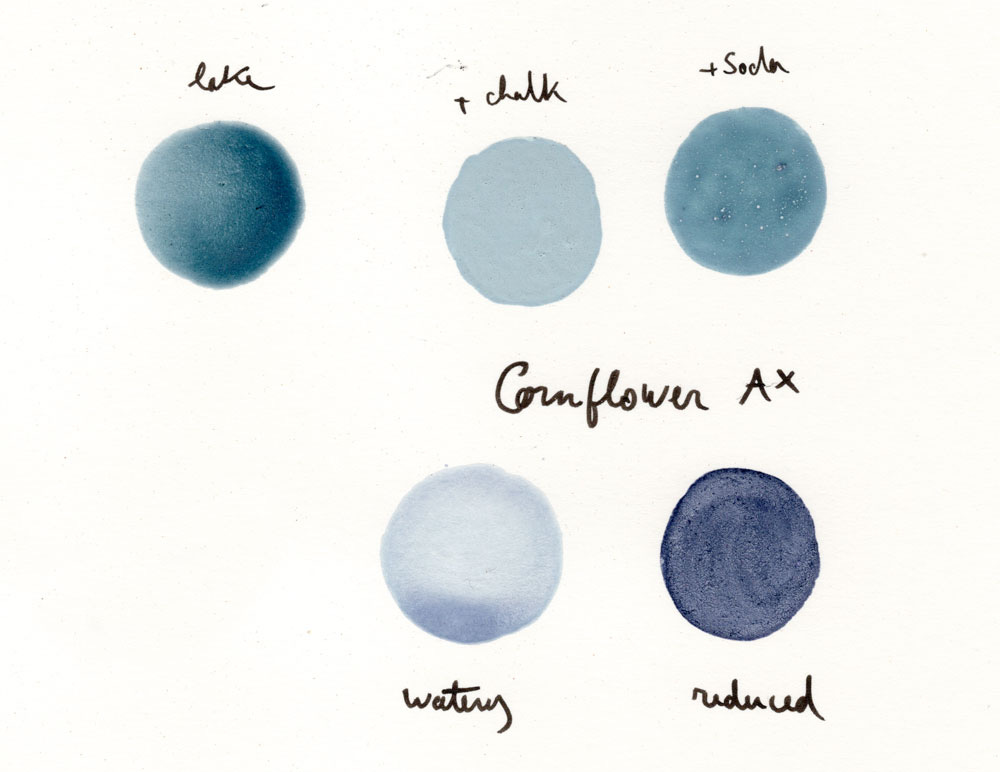

Anyway, the real test was trying this on paper, which I did here before and after inspissation: while still watery, then when really concentrated. As expected, contact with the alkaline surface of the paper pulled the hue back from purple to something much more blue. Hmm!

I made another small batch in the same way and separated it to add, respectively, chalk and soda. You can see these two in the top row. The results were encouraging enough that I made a proper lake by adding soda solution and gum, producing the striking blue in the pan and unlabelled swatch below.

Here’s a closer look at the freshly extracted dye (purple), how it turns blue when soda is added to make a lake, and a little later when the precipitation has become quite visible.

Collected after straining, it looks quite sumptuous, but left to dry a few days, both the quantity and colour of the pigment are more sobering. This is perfectly normal, though!

So far it looked like I would have to eat my words, but before I was able to write about it, I found myself in Devon with a whole, cornflower-sprinkled, wildflower meadow at my door.

This was my chance to experiment with a larger quantity of blossoms, but there was only one dry day that week during which I could collect them. So it was four or five days before I was able to bring them home and begin.

By then, the petals had started to change dramatically. Many looked completely bleached. Mere days after picking, the biochrome seemed to already be breaking down within the very petals, something I have not seen happen in this way before.

Given the amount of flowers, I used the decoction method (with alum) to extract the dye. It takes a practiced eye to see it, but the hue of the strained dye has a lot more yellow in it, as if the flavone was no longer masked. Can you see it? Where it was a clear cold purple, it’s now distinctly warm.

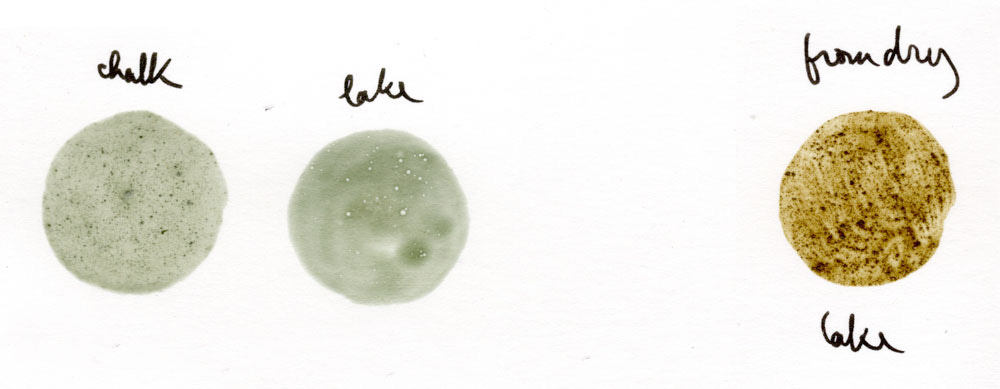

I divided my batch in two, to precipitate half with chalk and half with soda. Below are the chalk lake, dried in the bain-marie, and the soda lake before drying, both looking green in the gills. even worse are the swatches painted on paper. To complete the test, I dug up the last of my dried cornflower petals and put them through the same process; you can see that at the far right. All of these were a far cry from my first batch.

I can think of two possible reasons for this deterioration:

The flowers were visibly altered by the time I processed them, so it's the fact they weren't fresh that killed the dye. The protocyanin's quick breakdown may have let the flavone out, hence the greenish and muddy yellow results.

Due to the bigger quantity, I processed this batch with a lot more water, and both lakes remained wet much longer than my first batch. I already know that water is destructive to flower pigments, so it could be the culprit.

It could be a combination of both factors.

Meanwhile, I came across a handful of flowers near home, and decided to make a lake again to verify I could reproduce my initial success. This sequence should look familiar by now. Notice once more the clean purple of this extraction vs. the redder purple of the wilted batch.

At least we know that the fresh flower does make a blue ink, right? Oh if only it were that simple. Remember those first-generation swatches that were so promising? Two weeks later, this is how they looked: still lovely, but all of them noticeably greener than in original photos. Whether it's the effect of the soda content, or the paper surface, or simply the protocyanin's fragility, the sought-after blue was already gone.

But I had left the prepared colours to dry, so in principle those should have been safe from further changes. I tried painting new swatches from them, shown below. The inspissated ink, which I dried quickly, held up quite well. The chalk lake was only slightly changed, but the soda lake was now a deep sea green! I believe this is again the effect of water, because it took several days to dry in its seashell and I did notice it was turning green over that time. The lone swatch in the top row was painted from the lake powder that was left to dry. It’s only just before painting that I mixed it with gum and a little water, and the difference is noticeable, a petrol blue.

My conclusion from all this is that cornflower is one of those blossoms of which you can only capture the stunning hue fleetingly, like grape hyacinth or carnation, and one must learn to delight in the experience without seeking to hold on to it. And that none of the authors who dutifully repeated that cornflower can make blue ink had any real idea what they were talking about.

While I was busying myself with tests, Venetia Jane was looking for texts to shed some light into the “blue ink” claim that got this whole investigation started. She’s the one who located the myth’s origin thanks to a passage from Artists’ Pigments: A Study in English Documentary Sources by Rosamond Drusilla Harley, pp65-66. Here are the extracts, before I clarify them:

“Seventeenth-century writers were well-aware of the fugitive nature of many of the organic colours which were available then, particularly of those made from flowers. It was not a painter but a scientist, Boyle3, who recommended a blue dye prepared from cornflower petals, and, such was his reputation, that the colour was recommended for water-colour painting in some eighteenth-century books, sometimes under the name cornflower blue and sometimes as Boyle’s blue or cyan blue. The colour was strongly criticised by Hoofnail, but mention of the colour in other books, largely those which derive a number of comments from The Art of Drawing, 1731, has left an unfortunate and probably erroneous impression that eighteenth-century painters in water colours were heedless of permanence. There is no evidence that cornflower blue was ever supplied commercially.4”

Also this paragraph on p21:

“Any impression of complacency concerning the permanence of most organic colours left by the author of The Art of Drawing, 1731, is dispelled by the forthright condemnation of cornflower blue and other dyes which was made by John Hoofnail in New Practical Improvements. . . on some of the Experiments. . . of Robert Boyle in 1738. Apparently, Hoofnail had come into possession of Boyle’s manuscript but he was disappointed to find that it included only experiments and no detailed recipes. His book is composed mainly of quotations from Boyle with a commentary on the experiments which he had carried out himself.”

The story, therefore, goes thus:

Boyle experiments with cornflower and discovers he can extract blue from it. Whether he stops at the dye or goes further to make a lake is not clear, but what is clear is that he’s not a practicing painter and only has a vague understanding of what is required for watercolour; he also in all likelihood doesn’t test for lightfastness or longevity, but in his excitement recommends its use in painting.

Impressed by Boyle’s reputation, some authors pick up his recommendation without question, notably, in 1731, the author of The Art of Drawing, a book that seems to have as influential as it was unrigorous.

By the time the more the practically-minded John Hoofnail, who had some scientific training, makes his own tests and refutes the suitability of Boyle’s blue in 1738, the damage is done: the myth of cornflower blue has set in and made its way into enough publications to be picked up by otherwise reliable herbalists, who have been handing it down5 without question and without verification, in books and now online, since the 18th century.

The moral of the story is that if you come across a colour claim about any plant, look for visual proof. A search engine should be able to dig up some photo of ink samples or dyed fabric. If nothing of the sort is to be found, it’s probably just words on the breeze.

More organic colour experiments:

I should mention that the timing, while coincidential, worked out perfectly as I am now reprinting a small run of the book. As a result of this thread, I added cornflower to the book, along with heather, madder and myrtle. Read more about it on this page, which has links to purchase it either in print or as an ebook.

One of many reasons why labeling all experiments is so important.

Robert Boyle (1627-1691), Anglo-Irish polymath largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, with emphasis on “modern” and a good serving of “by Europeans”, because Abu Bakr Al-Razi (865-925) was unquestionably the first to make a “systematic classification of carefully observed and verified facts regarding chemical substances, reactions and apparatus, described in a language almost entirely free from mysticism and ambiguity” (Wikipedia). Both men were alchemists in that they believed in the transmutation of metals. And both men made contributions to the arts based on their chemical discoveries, but only Al-Razi did so successfully… (so successfully his recipes were still the cornerstone of all Arabic inkmaking treatises centuries later, and I use them myself.)

This is no surprise at all, as it's simply not possible. Whether the colour deterioration I experienced was due to the flowers being over two days old, or to prolonged wetness, the conclusion is the same: this process cannot be scaled up. One can't prepare a good-sized batch without time and water; the paint won't survive in a tube; it will turn green when left to dry in a pan; and we saw that even once painted it immediately starts to turn.

In A Modern Herbal (1931), also shared with me by Venetia Jane, Maude Grieve also adds: “It dyes linen a beautiful blue, but the colour is not permanent”. I don’t know whether it does, textiles are not my area and I would need a large quantity of flowers to even test it, but I do know that Centaurea cyanus is completely absent from any and all manuals written by actual dyers, including the bible of all dye plant books, Dominique Cardon’s Le monde des teintures naturelles.

So interesting. I read it because the lure of this color in the wild is something almost visceral and definitely somewhat spiritual to me. Every season I witness an explosion of chicory along the roadside where I live. This color longingly calls to me and I can’t tell why. The emotion it conjures in me is unlike any other that I come across in nature like autumn leaves and fields of sunflowers for example. I participate with this color in a way no other color in nature does. Thanks for your work here!

How do myths begin? Read this piece of masterful sleuthing, ostensibly about an enigmatic blue, but applicable to almost any colourful rumour.