When I was translating the 13th century scribe’s handbook Tuḥaf al-Khawāṣ by Al-Qalalusi1, citizen of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, I came across what I was sure were some sneaky uses of wine in some recipes. I say “sneaky” because wine is never mentioned by name, as if to keep the controversial substance below the radar.

Andalusia has produced wine since Phoenician traders founded Agadir (modern-day Cádiz ) around the 9th century BC. Under the Romans, this was a full-blown production, with Spanish wines being exported to every part of the Empire. This carried on uninterrupted during the Islamic period: despite the Qur’an’s disapproval of khamr (intoxicating wine), several rulers owned vineyards, produced, and drank wine2, possibly under the guise of medicinal purposes. They even introduced the distillation process to Spain3.

Knowing this, and based on the following passages, it seems to me that wine was more involved in certain crafts than it would seem at a casual glance.

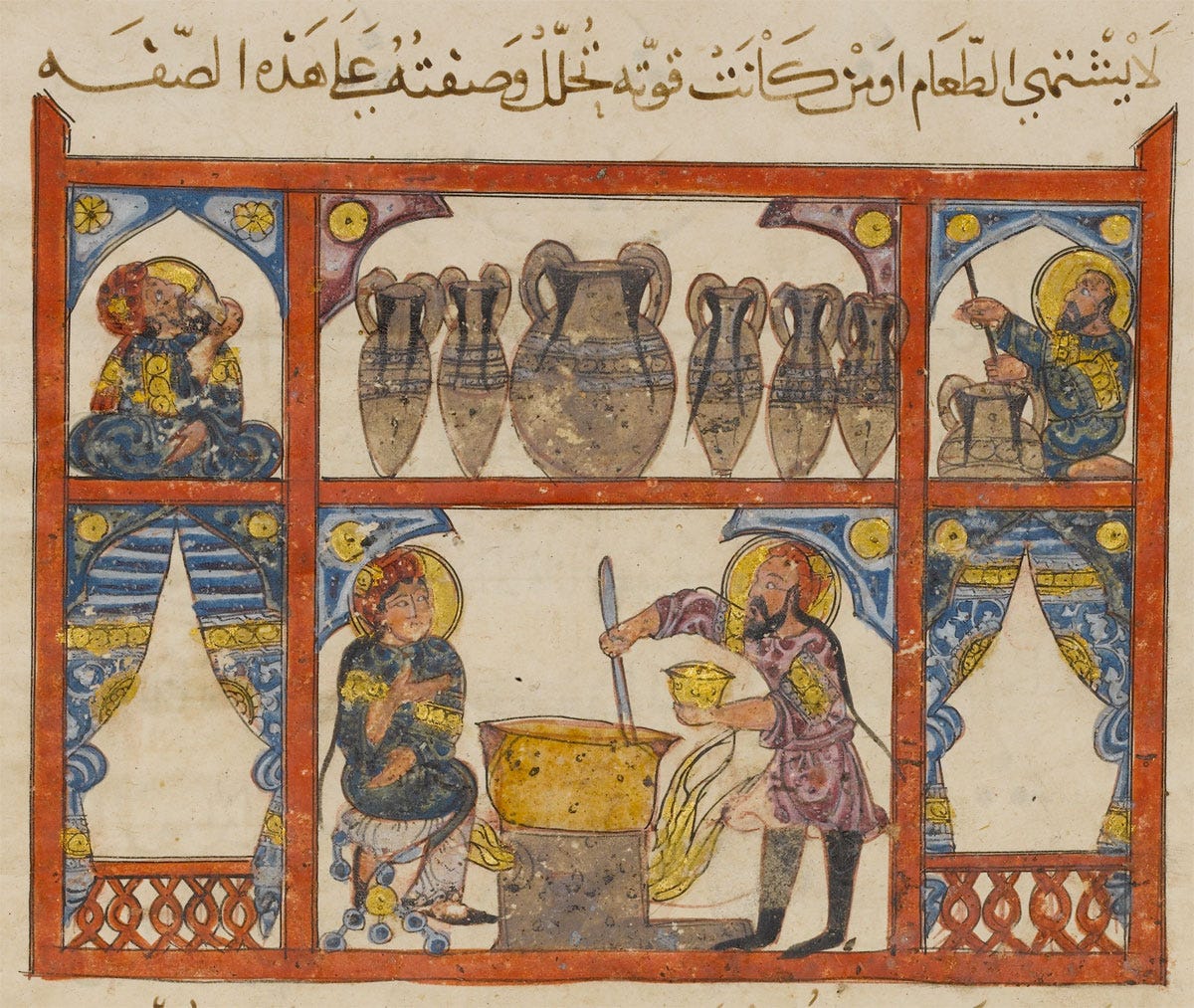

What first clued me in is a series of recipes that mention dipping in a khābiya. A khābiya is a large round jar, as seen in the image above4, but notice the recipes in question:

What is very clear from them all is that a dip in this famous khābiya alters the colour of the dyed cloth. Equally clear is that it can't be the jar itself having a magical effect on the dye! What is really being not-spoken about here is what the khābiya contains in the first place. So what is this particular type of jar used for?

I rely a lot for terminology on Nawal Nasrallah's wonderful translations of medieval cookbooks, which include gigantic glossaries worth their weight in gold. Her volume on the 10th century Annals of the Caliph's Kitchen, defines the khābiya thus:

The editors of Marwan Ibn Janah's On the Nomenclature of Medicinal Drugs agree:

In addition, Lane's Lexicon records the archaic بنت الخابية "daughter of the khābiya" as a word for “wine”.

There seems little doubt then that the term khābiya here is a synecdoche5 for wine. And what else could it be? If it were, say, pickling liquid, its components and proportions would have to be specified. It’s also not vinegar because that is mentioned by name over 40 times in the text, with “wine vinegar” (khall khamr) specified 6 times. Wine vinegar was perfectly permissible and was consumed as a condiment as well as used in other preparations. The existence of winemaking itself was not something the author was trying to keep quiet, and we find another witness to its presence within this group of recipes:

Ṭarṭar or cream of tartar is potassium bitartrate: a crystal that specifically forms in wine casks during the fermentation of grape juice. This is perhaps the most famous byproduct of the wine industry and if you bake, you probably have some in your pantry. The reason it’s used in the dye method above is for its acidity, which modifies the colour of lac towards red, resulting in a vibrant carmine.

Perhaps the whole khābiya business was on the basis that, though it was fine to stock vinegar, it was better not to declare that you also kept a store of actual wine – although two “industrial” recipes in there do call for wine directly6. Or perhaps there was no actual intention to be discreet but this figure of speech was so commonly used that it was just normal to use it (the way we routinely say “a drink” to refer to an alcoholic beverage or “a cuppa” for tea). I don’t honestly know, but here’s one more euphemism, looking more closely at this recipe:

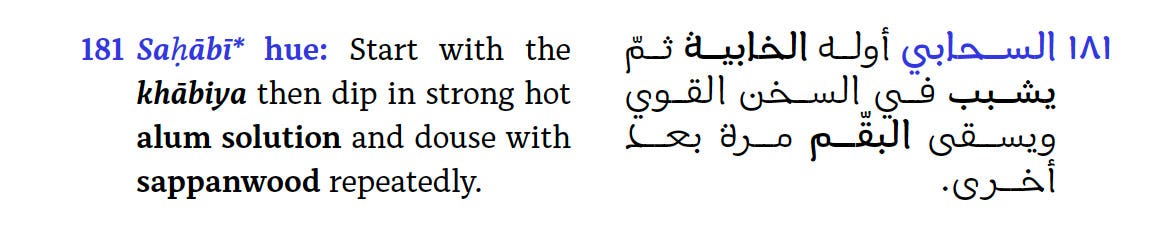

This is to achieve the colour of “saḥāb”. The only information to be found about that word in any dictionary is that it denotes a group of clouds heavy with rain. What kind of colour is that?! Particularly when the recipe above is so obviously going to yield a reddish hue. But once again Lane's Lexicon offers up an archaic usage: "water of saḥāb" is yet another word for “wine”. Which rather makes more sense, especially when you start by dipping the cloth in actual wine...

Whatever the explanation for the choice of language, I feel sure at least that a couple of mysteries – the natures of khābiya and saḥābi – are resolved satisfactorily by reading them both as “wine”. But if al-Qalalusi was really trying to avoid censorship, he made it so any practitioner consulting his handbook would be able to read between the lines.

Based on this article.

Along with the word alcohol, but in Arabic al-kuhl actually refers to eyeliner. How the word got attached to spirits as it was adopted into Spanish is detailed here. If you’ve come across the old fib of “alcohol” deriving from “ghoul”, discard it for the stupid nonsense from an attention-seeking charlatan that it is.

Source: Manuscript of an Arabic Translation of De Materia Medica of Dioscorides, dated 621 AH/1224 CE, probably Baghdad. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Synecdoche (/sɪˈnɛkdəki/ sih-NEK-də-kee): a figure of speech in which a term for a part of something is used to refer to the whole (pars pro toto), or vice versa (totum pro parte).

For preparing ethanol and naphtha, respectively. With only two surviving copies of the text, both made centuries later, it’s really hard to be sure these were not inserted by a later copyist, a common and aggravating practice.

I don't know if the guy in the illustration is making wine, but the look on his face - suggesting he is, at the least, a character - makes one wonder. :D

Wonderful piece. I would love to see the image you refer to at the start, am I missing it?