Before I begin, I want to express my gratitude to all the readers who recently upgraded to a paid subscription! Some time back I decided not to introduce a paywall, hoping instead to inspire readers into supporting my work, and I really appreciate everyone who decided Caravanserai was worth it. Every subscription helps this independent research of mine.

Today’s post still has a touch of alchemy as I share the process of extracting the “heart of the safflower” قلب العصفر, a sumptuous red pigment hidden inside deep inside a yellow blossom.

Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius), which in the Middle East today is sold as "saffron", is used in cooking to dye dishes a bright yellow hue at a fraction of the cost of the real thing1. What is less known to the public now is that their ancestors were far more interested in its highly valued red pigment, and went to great lengths to collect it.

I first tried this process based on medieval Arabic texts I was deciphering for my book Inks & Paints of the Middle East, and have continued experimenting and refining it for myself ever since. The red pigment, carthamin, is very light-sensitive, but was a staple of the Islamic book artist’s palette. The laborious process of extracting it, which requires a precise balancing of ingredients, makes the astounding end result particularly rewarding.

Much of the labour is due to the fact the flower contains two biochromes (organic pigments), and the one most readily released is yellow and fairly useless for anything other than food colouring. This yellow needs to be completely washed out before extracting the red carthamin ('akar عكر) can begin.

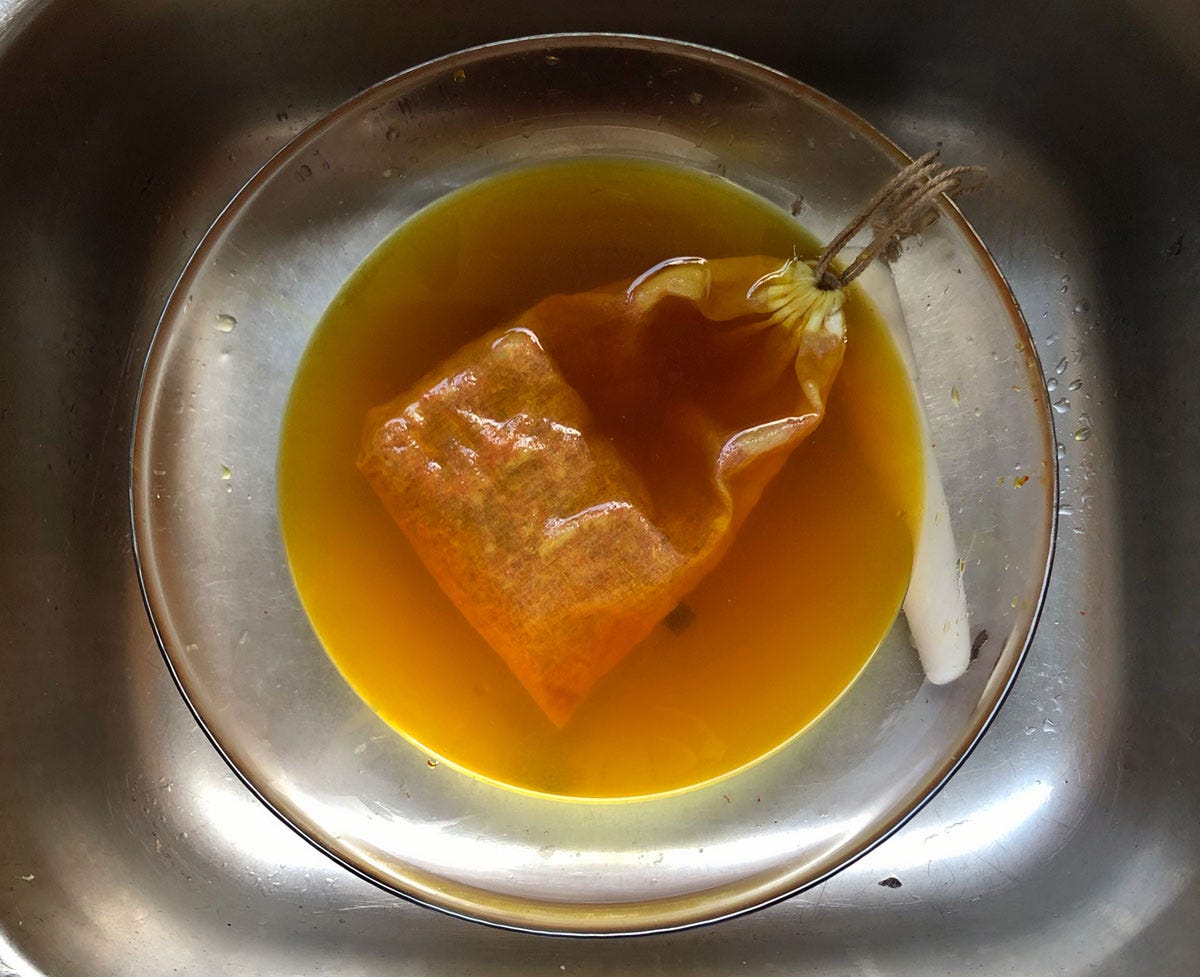

When the powdered flowers, here gathered in a cloth bag, are first plunged in water, an abundance of yellow is released:

The safflower is kneaded, then the water is replaced. Over and over, as many times as necessary until no yellow is released at all anymore. Meanwhile, the cloth gets dyed a bright pink, as if the carthamin couldn’t help betraying its presence.

Phase two is extracting the carthamin itself, by soaking and kneading the safflower in an alkaline solution. Both blossoms and bag now release all of their colour into the liquid.

The flowers are removed and every last drop of dye squeezed out and into the container. This is the moment that’s always magical no matter how many times I do this: vinegar or lemon juice is added to the dye, which instantly turns a deeper red.

Precipitation begins immediately, albeit at its own slow pace. After a few hours, a solid2 red pigment has formed and separated from the liquid.

Medieval craftsmen carefully poured out the unwanted liquid, but I pass the whole thing through a coffee filter. When it’s dried out a little, collecting it by carefully scraping what is essentially red paint off the filter is my absolute favourite part.

What happens then depends on what one wants to do with it. I bray it with a little gum so I can dry and store it as a powder.

The dye itself was of course used with textiles (you saw the colour of that bag!), but also on pieces of paper. The pink or peach result could be cut out into shapes and pasted inside a book to make large areas of colour3, as painting them in wouldn't quite produce the same result. Below are paper and silk yarn dyed with un-precipitated safflower from a more peach-hued batch. Left in natural light, they faded almost completely in a few weeks.

The precipitated paint is more concentrated, more red, and more enduring, though it’s certainly not suitable for wall art. Qur’anic illuminators used it, along with other organic reds, on top of gold leaf: their transparency made for a lovely enamelled look. But such splendid Qur’an productions belong to a past that has been lost to synthetic colours. Safflower red carries on as a dye, for instance in Japan where the extraction process is highly sophisticated, and, until recently at least, in North Africa as a natural rouge, precipitated and dried directly into a purpose-made container.

You’re expected to ask for "real saffron" if you want the actual spice.

It’s actually paste-like at this stage, but what this means is it’s no longer dissolved.

As seen, for instance, in the Ruzbihan Qur’an (Chester Beatty Library).

Fascinating process. Always humbling to see what book creation truly entailed in the good old days.

Thanks for the very interesting post - and for mentioning the Ruzbihan Qur’an, which I found online...

https://viewer.cbl.ie/viewer/image/Is_1558/6/LOG_0000/

... with some gorgeous images in the blogposts on its complementary gold & ultramarine

https://chesterbeattyconservation.wordpress.com/tag/the-ruzbihan-quran/