This poetic title is the translation of the name of an actual place, the town of Deir el-Qamar1 in the Chouf region of Lebanon. No matter how far I travel and how much I see, Deir el-Qamar remains one of the most lovely places I know. For reasons too far-reaching to go into, the Chouf as a whole has been preserved from rampant urbanisation, and the traditional character of its architecture has been lovingly preserved, even if a troubled history means many of these homes stand empty today.

I think of Deir el-Qamar as a village because it has the feel and charm of one, but between the 16th and 18th centuries this was the capital of all Mount Lebanon and is endowed with a caravanserai (or khan as they’re locally known) as well as the palaces of Emirs. If these are not particularly visible, it’s because the country was under the yoke of the oppressive Ottoman empire, and it was imprudent to taunt the colonial rulers with showiness. The splendour retreated entirely inside the sober walls, at least until the construction of the opulent Beiteddine palace, but that’s a story for another day.

The palace that inspired this post, and possibly this whole Substack, is the saray of Emir Youssef Chehab (built in phases during the 18th c.), today the seat of the City Council. It stands right on the square and is so there and familiar that it never occured to me in my entire life to take a photo of it, for which I’m kicking myself now. Until I visit again and rectify my oversight, here’s a good view of it from above.

I’ll have to come back to this building in future to focus on different features – contained as it is, it had plenty to hold my attention – but the one I wanted to share today is a very particular decorative technique. This is the main room of the palace, under the dome.

Here’s a closer look at the windows on either side:

I’m entranced with this technique, for which I’m still looking for some historical mention. The only information I have about it at all is what a council worker told me on the spot: the motifs are carved into the stone, then each space is filled with a coloured paste made of marble powder, natural pigment, egg white and pine resin.

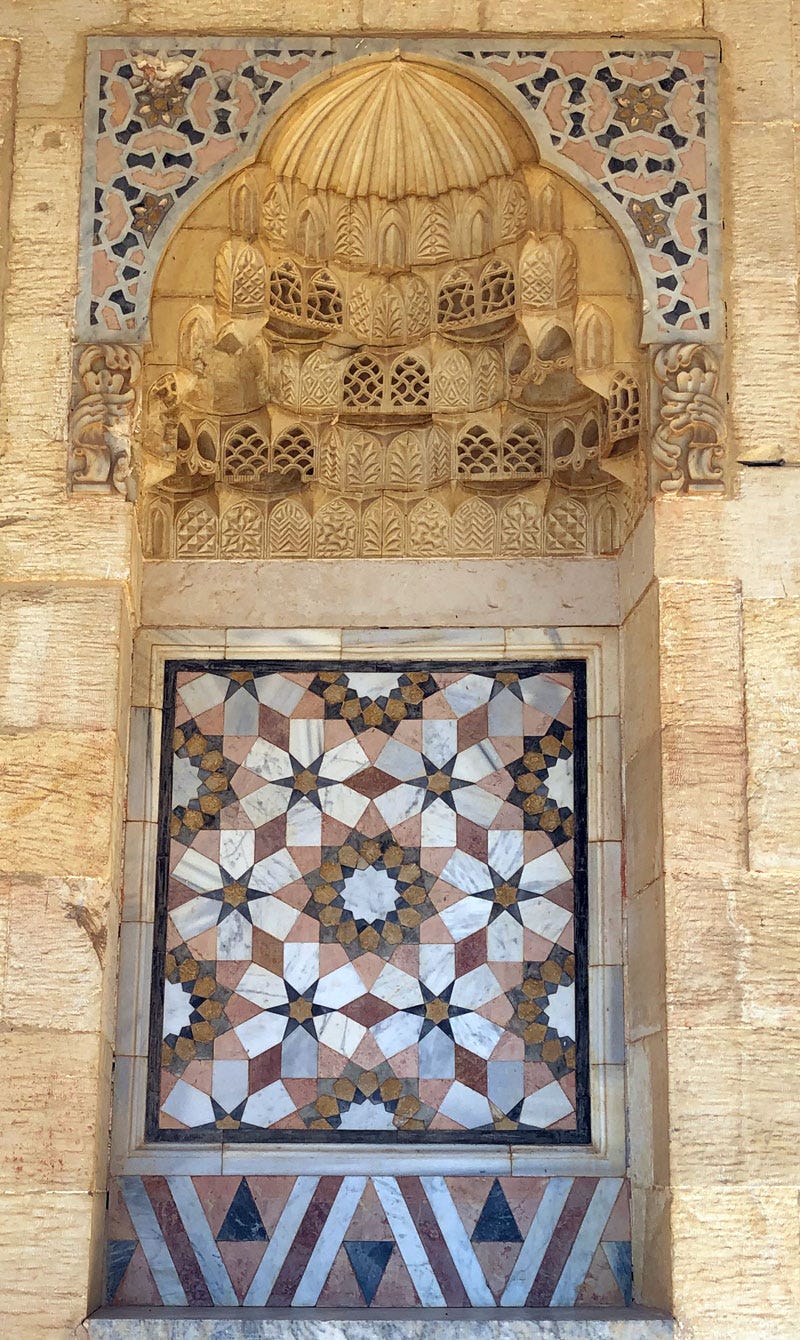

This paste inlay may be a cheaper version of the marble inlays that characterise Mamluk decoration; their aesthetic influence was profound and lasting, and still defined architecture well into the Ottoman period. For comparison, here’s an example of marble inlay from Beiteddine:

I’m not satisfied to see paste inlay as merely a poor man’s solution, as it strikes me as an alternative that drew on local stonecutters’ own skill with local stone, as opposed to imported materials and craftsmen. It doesn’t have the sharp precision of marble inlay, and doesn’t communicate expensive taste in the same way, but it offers at least two advantages: there is no grout, and the use of pigment allows for a greater range of colours. Besides, I found the paste technique used in Beiteddine itself:

Back to the saray and looking back towards the door, notice the marks on this arch:

Every stone of this arch was adorned with complex paste decoration, of which only the imprint remains.

In another room, one arch has survived well or perhaps been restored; I joined photos together to show a long sequence of paste inlays motifs. The’re beautifully random, though the two halves of the arch mirror each other.

And more to be found in every nook and cranny…

These are not limited to the palace: outside a few steps away, by the synagogue, this portico bears the traces of this technique on every single arch.

Here we have more randomness than ever, even flipping between geometric patterns and stylised plants, and it’s pretty clear the stones are carved before they’re put into place. It’s also clear that the coloured paste is sadly not very resistant to the elements, but maybe it was meant to be regularly maintained, and history didn’t allow that…

One last detail for the sake of completeness, prised from the darkness, an intriguing motif of plant and stars.

There is much more to see about Deir el-Qamar so I expect we’ll revisit it. The last time I was there, it was a bright day in December and in the forsaken garden of a shuttered house, a bitter orange tree was laden with golden fruit.

We did the decent thing and gathered as many of these treasures as we could, which I then made into a delicacy: a cordial or syrup we just call busfeir, our name for these oranges. As they’re in season right now, I leave you with the recipe2 – a flavourtrack in lieu of a soundtrack…

Bitter orange syrup شراب البوصفير

Juice the oranges, preferably using a manual juicer to avoid the very bitter pith. (The rinds can be used for marmalade.)

Filter through butter muslin/cheesecloth. Work out the weight of the juice you extracted.

Mix the juice with the same weight of sugar in a non-reactive pan. Bring slowly to the boil, stirring until the sugar is dissolved.

Boil for at least 15 minutes, taking it off the heat before the liquid sets. Skim off any froth.

Pour the hot syrup in sterilised bottles, filling to the rim, and seal immediately. Leave to cool then store in the refrigerator.

To serve: Pour about 2 tbsp of syrup into a glass and fill with water. Enjoy!

An origin story reported on Maronite Heritage goes that a Druze Emir in Baakline looking out towards Deir el-Qamar saw a light coming out of the hill. He sent his soldiers to dig up the site with the instruction: “If you find a Muslim symbol, build a mosque. If you find a Christian symbol, build a church.” The soldiers set to work next morning and found a rock with a cross on it over the moon and Venus. While the story has all the elements of a story, the detail of the moon and Venus is unusually specific; in all likelihood there was an early church there built over an earlier temple, which is not uncommon in those parts.

Based on the recipe provided by Barbara Massaad in her book Mouneh, is a superb collection of traditional Lebanese winter preserves.