Today I’m sharing an extract from my book Stories of Abjad, which came off the press only a few days ago. I wrote it to accompany the artist book in the video below, for which the starting point was the relationship of the Arabic letters with numbers. The section I’m sharing describes this early alphanumeric system and the transition to the Indo-Arabic numerals we use today, which is subject to a lot of misinformation!

The Abjadi Order الترتيب الأبجدي

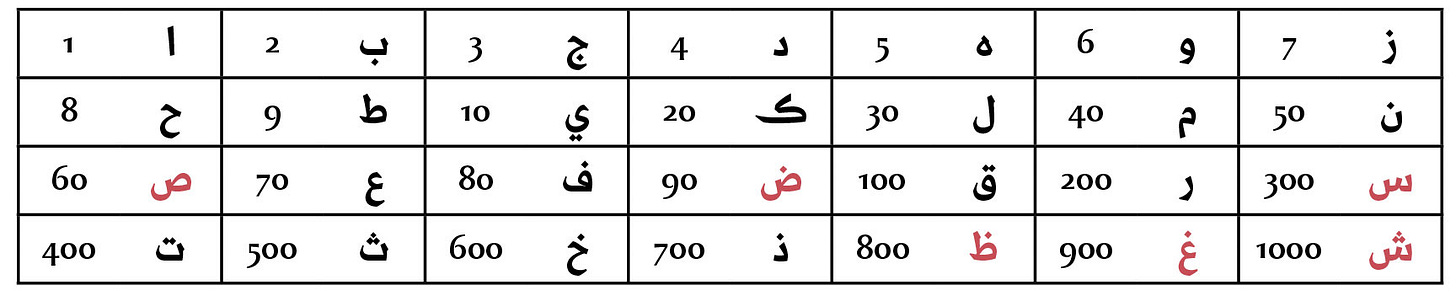

Several scripts of the ancient world were alphanumerical in nature: they didn't have a dedicated set of signs for noting numbers, instead assigning numerical values to existing letters. In Semitic alphabets – Aramaic, Syriac, Hebrew, and of course Arabic – all the letters were used, in the order of the alphabet: the first nine letters would represent numbers from 1 to 9, the next nine from 10 to 90, and so on. In this system, the number of letters available determines the highest value that can be written with a single letter, and for the twenty-two letters of most Semitic writing systems, that value is 400. But when the Arabic script developed out of the Nabatean, six letters had to be added in order to express the full range of Arabic sounds. These letters, the rawādif1 روادف were derived from existing ones and differentiated by pointing2, the practice of adding diacritic dots or dashes to differentiate the derivative. This brought the number of Arabic letters up to twenty-eight, thereby equipping the script with numbers up to 1000, but also paving the way for exceptional symbolic and cosmological speculations (discussed further in the book).

The oldest letter sequence, directly inherited from Nabatean, is believed to be the “Western Abjad”3 which survived longest in the Maghreb:

The Eastern system came about relatively late, as the last – or at least most successful – of a number of different attempts to reorganise the letters. This is the sequence my Book of Abjad is based on4:

The Eastern Abjad is commonly vocalised in the mnemonic phrase:

ابجد هوز حطّي كلمن سعفص قرشت ثخذ ضظغ

Abjad hawwaz ḥutti kalamon sa'faṣ qarashat thakhadh ḍaẓagh

Grouping the letters in this way to form eight “words” appears to have been a very old practice, actually predating the Arabic script and its extra letters, because there are reports of early attempts among Arabs to make sense of the six nonsensical words. They were variously interpreted as the names of mythical giant kings of Midian, or the names of the six days of Creation in the Torah, among others.

Letters as Numbers حساب الجُمّل

The use of abjad letters as numerals is referred to as ḥisāb al-jummal. Numbers are treated like words, starting with the largest number and writing leftward until the smallest number. A few examples:

11 يا

45 مه

237 رجز

1,999 غظصط

The largest value for which a letter is available is 1,000, but this can be multiplied as required by placing smaller values before غ :

2,000 بغ

5,500 هغث

12,000 يبغ

400,601 تغخا

The most visible applications of this system can be found on scientific instruments, in particular astrolabes, which still display the abjad complete with certain archaic features for a suprisingly long time. We also see signs of abjad use in early and Abbasid Qur’ans, where the letter ha was used as a marker after a series of five verses.

Despite its long survival in specialised contexts, this alphabetic numeral system was displaced fairly early as Arab mathematicians adopted a more practical device for working with numbers.

The Indo-Arabic numerals الأرقام الهنديّة

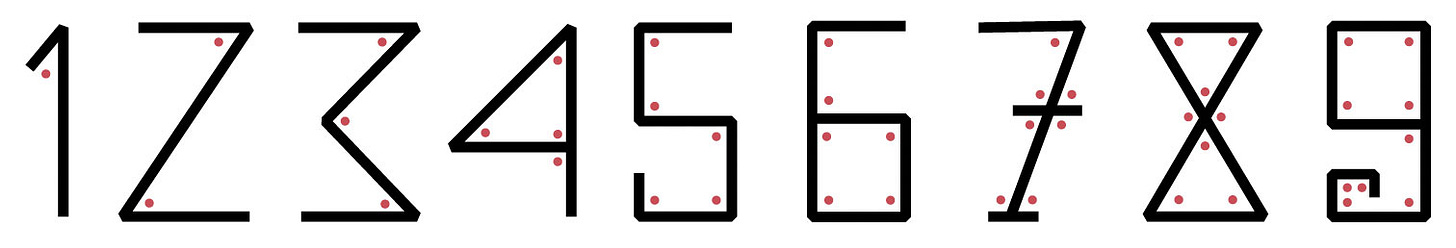

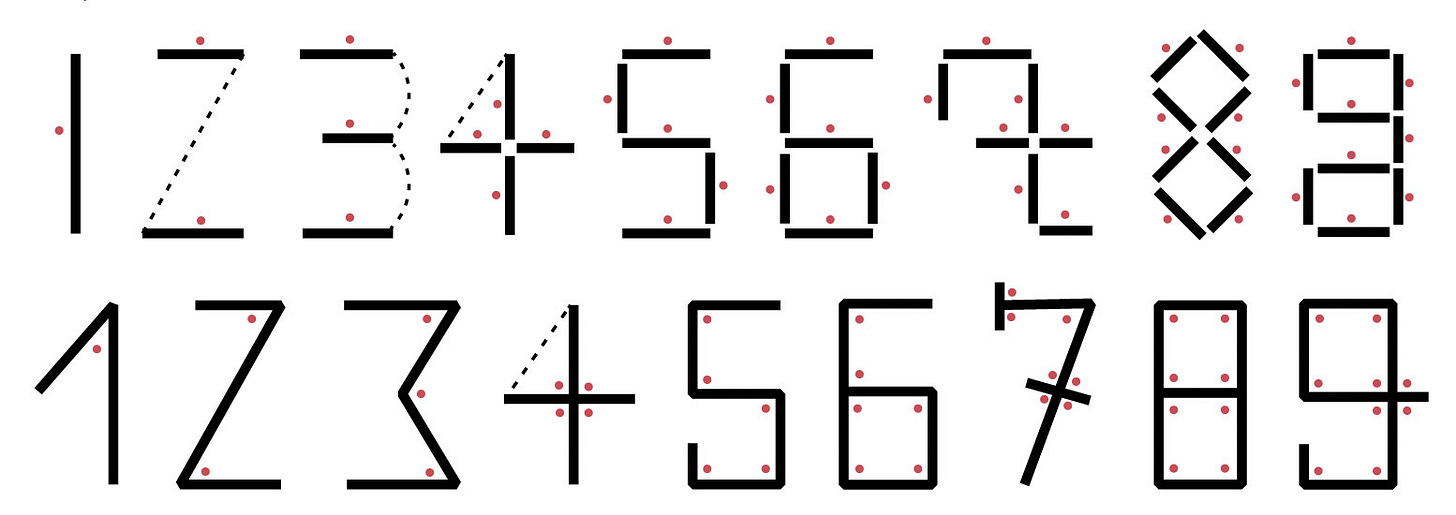

There is a myth of breathtaking idiocy going around the Arab world, that was already circulating long before my time but was given wings by the advent of the Web. It claims that the Persian mathematician al-Khwarizmi – he whose latinised name Algorithmo has become a nightmare for social media users – designed the Arabic numerals as shapes that each contained a number of angles corresponding to its value. You may have come across the following figure before, proliferating across the interwebs like a bad meme:

The true origin of this diagram is a very different story, but let us take events in their proper order. Clutching at the above origin story for these numerals betrays a fundamental inability to understand what made them an innovation. The figures in themselves would be meaningless if they weren't part of the crucially different reckoning system that is positional notation, which we all use today: we place digits in virtual columns corresponding to units, tens, hundreds and so on, and if one column has no value we place a "naught" symbol in that position. Thus we write: 804, in contrast to abjad ضد or Roman DCCCIV.

This positional notation, complete with the concept of zero, came to the Arabs from India, probably via Persia (as did a bounty of goods and words ranging from oranges to indigo) – in fact Persianate cultures still retain digit shapes closer to the original Indian models. Al-Khwarizmi certainly contributed to the popularisation of the system when he wrote On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals (كتاب الحساب الهندي) c. 820, but his is merely the oldest known text in a veritable genre of writings on Indian computing. Another Baghdad-based mathematician, Al-Kindi, wrote On the Use of the Hindu Numerals (كتاب في استعمال العداد الهندي) c.830, and was followed by Al-Uqlidisi (c. 952), Kushyar ibn Labban (10th c.), Abd al-Qahir al-Baghdadi (11th c.) and others, all of whom describe the nine “Hindu letters” along with zero, and all trace them back to India. Yes, even zero: its etymological ancestor ṣifr may be of Arabic origin, but it's merely a translation of the Sanskrit name shūnya (”naught”) which Indian mathematicians used for it, even as they wrote zero as a small empty circle – or the same dot used today in the Arab world.5

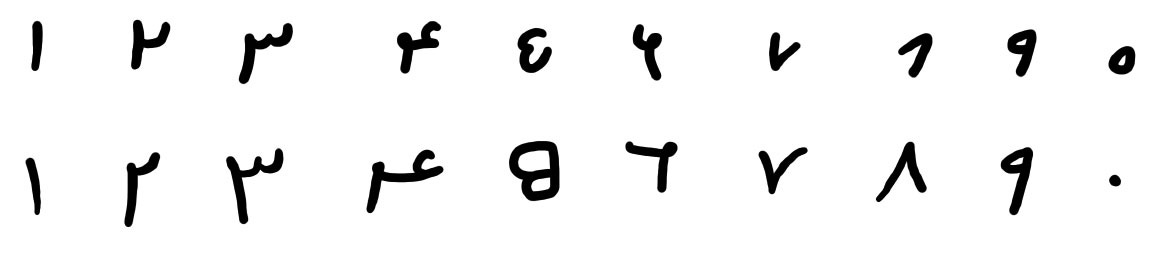

Here are the Indo-Arabic numerals that are used today in the Mashriq:

٠ ٩ ٨ ٧ ٦ ٥ ٤ ٣ ٢ ١

Note that these are written with the largest column on the left and units last on the right, contrary to abjad numerals but exactly as they are in Latin scripts: 1805 is written ١٨٠٥.

This now-standard design6 only asserted itself after a great deal of variation and transformation, sometimes even within the same manuscript. Below are only two examples of early, complete sets of numerals:

The Eastern numerals did not stick in the Maghreb, however, where the numerals evolved still further from the Indian originals, and much closer to our modern digits. These Western Arabic numerals are sometimes referred to as ashkāl al-ghubār ("dust figures"), and they sent scholars of the past century on a merry chase to trace back what appeared to be an independent lineage of numbers. This was much ado for nothing, as in the end it turned out ḥisāb ghubāri حساب غباري was simply the preferred name in the Maghreb for Indian reckoning, and the few surviving texts explicitly describe it as such. The term ḥisāb ghubāri arose not to imply a separate set of numbers, but to distinguish written calculus, which was done by tracing Indian numerals on a board covered with fine sand, from mental calculus (ḥisāb maftūḥ حساب مفتوح or ḥisāb hawā’i حساب هوائي).

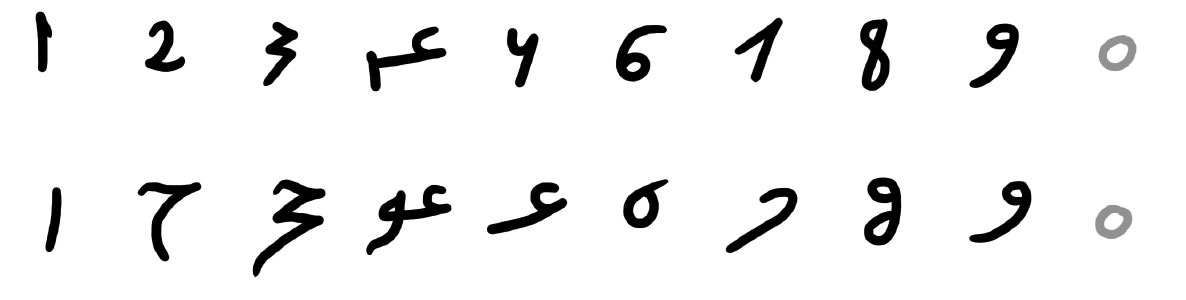

The evolution of Maghrebi numerals is difficult to fully trace due to scarce surviving evidence, but here are two samples:

The difference between the two may be clarified by a mnemonic poem7 that was in circulation. Undated, but written long before the fifteenth century, it describes the shapes of digits as familiar letters:

ألِفٌ وحاءٌ ثمّ حجٌّ وبَعدَه عَوٌّ وبعد العوّ عينٌ تُرْسَمُ

هاءٌ وبَعْدَ الهاءِ شَكلٌ ظاهِرٌ يبدو كالخطّافِ إذا هو وُرسَمُ

صِفرانِ ثامِنُها وألِفٌ بينَهُما والواوُ تاسِعُها بِذلك يُختَمُ

These verses compare:

1 to alif ا

2 to ḥa ح

3 to ḥa-jim حج (your screen font won’t display this resemblance as well as the original cursive script)

4 to ayn-waw عو

5 to ayn عـ

6 to isolated ha ه (again the font will display a modern and not so relevant form of this letter)

7 to a hook

8 to two zeros o linked by an alif ا

9 to waw و

It's obvious to the eye that the poem could have been describing the top sample, while the bottom sample is highly, even literally informed by the poem itself.

How the positional numerals made their way from the Islamic world into Europe is another topic, but it brings us back to the absurd origin story this chapter opened with. It's not until the fifteenth century that the Indo-Arabic numerals became well-known throughout Europe, and during the Middle Ages they were used in addition to Roman numerals, not instead of them. It must have been a little challenging for the average European to learn this novel system, because during the Renaissance diagrams were devised to help learners remember the shapes of the digits, either by counting their angles, or by counting their strokes8. That an imaginative stretch was occasionally needed didn't matter, because it was simply an aide-memoire.

Another fanciful origin story, claiming the "Latin number letters" were based on configurations of the fingers, was advanced by Jacob Leupold in the eighteenth century9 and picked up by at least one modern author apparently desperate to claim a purely Arab origin for the digits.

I've also come across an attempt to demonstrate that the Arabic letters, specifically of the Maghrebi style, developed directly into today’s Arabic numerals. While the tone leaves little doubt that it's yet another expression of history-bending nationalism, one could charitably suppose this particular attempt was based on misunderstanding the poem quoted above. While the poem’s comparison of numerals to letters is useful, some have taken these similarities as proof that the numerals came directly from Arabic letters – a classic confusion of correlation with causation.

Interested in reading more? Stories of Abjad is now available to order from my shop.

Meaning "the followers, those that come after", though I find myself unable to stop calling them the "rump letters".

The Arabic word is ta'jīm تعجيم, and a tired, self-serving and rather superior myth that's taken for granted in the Arab world is that this word derived from 'ajamī عجمي "Persian, non-Arab, foreign", because, supposedly, pointing was created with the expansion of the Islamic empire so that foreigners would be able to read Arabic properly. The truth is that ta'jīm is as old as the Arabic script itself, though it's not consistently used – when context makes a letter unambiguous, diacritics tend to be left out. Architectural Kufi also routinely leaves out pointing as it prioritises clean geometry and tight compositions. A very shallow understanding of the early tradition may have led to the belief that ta'jīm was unknown until the "enlightened" first decades of Islam, but it's my belief that the true origin of this word is the word 'ajam عجم “pip, fruit kernel”. Indeed the first diacritics were shaped like pips, influenced by their Syriac equivalent, or like the dashes left by the tip of the pen, not the dots or diamonds we know today. Ta'jīm therefore simply means “pipping” the text.

The investigation leading to this conclusion is detailed in Macdonald, M. C. A. “ABCs and Letter Order in Ancient North Arabian” in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 16 (1986): 101–68.

The reason for this choice is simply that I have a long-standing connection with the Eastern Abjad and it comes most naturally to me.

For the most up-to-date among the references on this topic, see Kunitzsch, Paul, "The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered" in Iqbal, M. (Ed.). (2012). Studies in the Making of Islamic Science: Knowledge in Motion: Volume 4 (1st ed.). Routledge: 3-21.

Despite being standard, it remains stylistically divorced from the Arabic script and doesn't harmonise with any style of it.

Quoted in Ifrah, Georges. Histoire Universelle des Chiffres. Seghers, 1981, p502. It's also transliterated in Kunitzch 2012, but with an error: after alif, the second digit is compared to a yā, when numerous examples similar to fig. 5 show the ḥā reading was well-established.

Reproduced from Ifrah 1981, p512. The author remarks "il est curieux de noter qu'une certaine tradition populaire, encore tenace de nos jours au Maroc, en Syrie et en Egypte, donne le second de ces moyens comme idée directrice de «l'invention du graphisme des chiffres arabes par un homme originaire du Maghreb.»" This suggests making Al-Khwarizmi the inventor is a recent embellishment, doubtless meant to add credibility to this frivolous claim.

Menninger, Karl. Number words and Number Symbols: A cultural history of numbers. Boston:Dover, 1969, p418.

Good article. I’ve recently bumped into the use of the Abjad Numerical System in studying some historical works. And it suddenly dawned on me that the one is indeed an ا. The two a -90 degrees rotated ب. The four a د without its standing tower, and so on.

The Hindus did add a 0 (and had the first credit-debit accounting system, called fortunes and debts at the time) but both worked off of the original Arabic Abjad Numerical Foundation.

thank you as always for your wonderfully detailed and "illuminating" essays!