I hope everyone’s having good holidays! I’m sneaking in one last post for the year between two celebrations. As a reminder for anyone who missed part 1, I’m preparing a full set of inks described in Ghāyat al-Hakīm (the Picatrix), one for each of the 36 decans. After the first two, I went on to tackle several red inks.

Leo 3

والوجه الثالث احمر رمّاني وذلك ان يغسل الزنجفر الرمّاني مراراً عن كباريته المغيّرة له ثم يضرب بماء عفص أخضر واتركه ساعةً ثم ضع فيه يسير صمغ وقليل لكّ واضربه وارسم به

“[The ink for] the third face is pomegranate-red. For this, pomegranate-hued cinnabar is repeatedly washed of its separated sulphurs, then it is brayed with decoction of green gallnut. Let it rest an hour, then add a little gum and some lac; bray and draw with it.”

Given that the range of the word “red” covers browns, comparing this hue to a pomegranate is a useful way to underline its clarity and brightness. In the scribal world of the time (and indeed for centuries before and after), cinnabar was the most highly rated red pigment, and lac was the most popular organic red. This recipe could very well come from an inkmaking book, and in fact an identical one can be found in the 11th-century Umdat al-Kuttāb, and another almost identical in the 13th-century Tuhaf al-Khawāss, where the only difference is that the dye from lac is replaced with dyer’s bugloss. Combinign a mineral pigment with a dye of supporting hue is a characteristic practice of Islamic scribes.

Cinnabar is a natural compound of mercury and sulphur, hence the recipe’s instruction to wash the ground mineral until it’s rid of all the sulphur that may have separated. It’s hard to obtain really good cinnabar crystals so I get it already powdered, and the washing step is no longer relevant. Here’s I’m mixing it with gallnut decoction; the gobs that appear are typical, and indicative of genuine mercury sulphide (which you may know as vermilion, the name of the same substance when it’s synthetised).

Lac on the other hand is a sticky resin secreted by an insect that forms large colonies on trees in India. The sticklac shown above is harvested from the coated branches, and it has been processed for millenia to obtain shellac. The red dye is a by-product of this process and is a rather wonderful product in its own right, typically used over gold for an enamelled look. Here I ground down the sticklac a little, and the dye is released by simply adding hot water (though there are also other ways for getting deeper and redder hues out of it!)

Because cinnabar is such an intense pigment, the lac isn’t going to visibly affect it (it could if we prepared extra-concentrated lac), but it ensures that even if the proportion of cinnabar is a little too small, it’ll still come out a vibrant red:

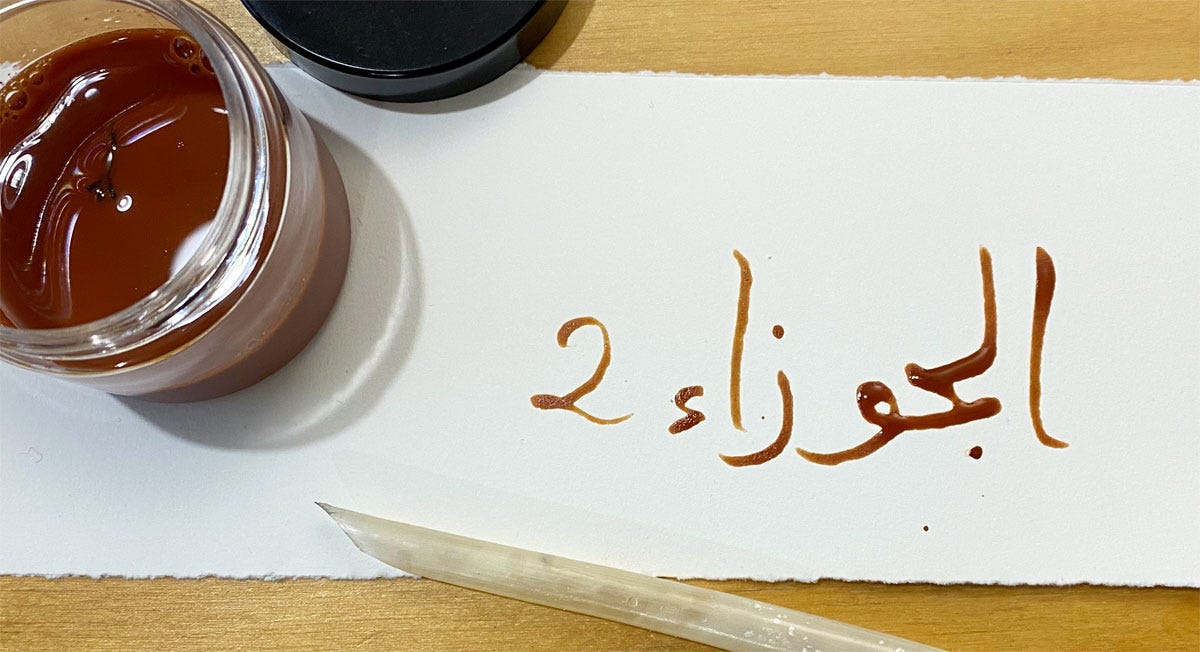

Gemini 2

والوجه الثاني مداده احمر يصنع من قاطر زاج احمر وزنجفر يوضع معهما يسير صمغ

“The ink for the second face is red, made from the filtrate of red vitriol and [from] cinnabar, to which is added a little gum.”

This one required careful reading, because at first sight, Arabic being what it is, it could be taken to mean “red vitriol and cinnabar, distilled”. But it would make no sense whatsoever to distill cinnabar, which is a solid powder. All you would do is get clear water out of it again. But the verb قطر can also mean drip or percolate, like coffee through a filter, and that makes complete sense if it’s applied to the vitriol. Vitriols were mined and therefore full of dirt and other impurities: before use, they had to be dissolved and decanted or filtered. So that’s what is added to the cinnabar, making the whole process look a lot less complicated.

Red vitriol, as far as I could ascertain (and I did look painstakingly into the maddening business of vitriol names) refers to ferric sulphate as well as to iron oxide. But iron oxide is a solid, and no longer soluble. So it could only ferric sulphate. I managed to source some, and you can see how in the jar below, in its dry form, it has the barest tinge of pink. But ALL iron salts, no matter their hue, do exactly the same thing when they’re completely hydrated: they instantly turn into, essentially, a rust bath.

Add this to the cinnabar, and the effect is pronounced because this is mostly a rust ink. As it dries, it oxidises and the result is is a deep brown-red. Here the cinnabar does little more than add body to the ink.

Aquarius 1

الدلو الوجه الأول منه أحمر مسكي يصنع من الشيبان وهو دم الأخوين ويسير صمغ

“[The ink for] the first face of Aquarius is musk-red, made of sheybān which is the blood of the two brothers [= dragon’s blood] and a little gum.”

Well, this is exciting. The simplest of inks, but with an unusual material. Dragon’s blood is the resin of Dracaena trees, particularly from the island of Socotra.

It’s mostly used medicinally, and I haven’t found any other references to using it as an ink for professional non-magical use – understandably, as its texture is quite tricky. Mixing it with gum and water below, it’s quite thick and molasses-like – quite pleasing, just not even or flowy.

Nevertheless, it’s usable, and with the way it clots, I can see why it’s referred to as blood!

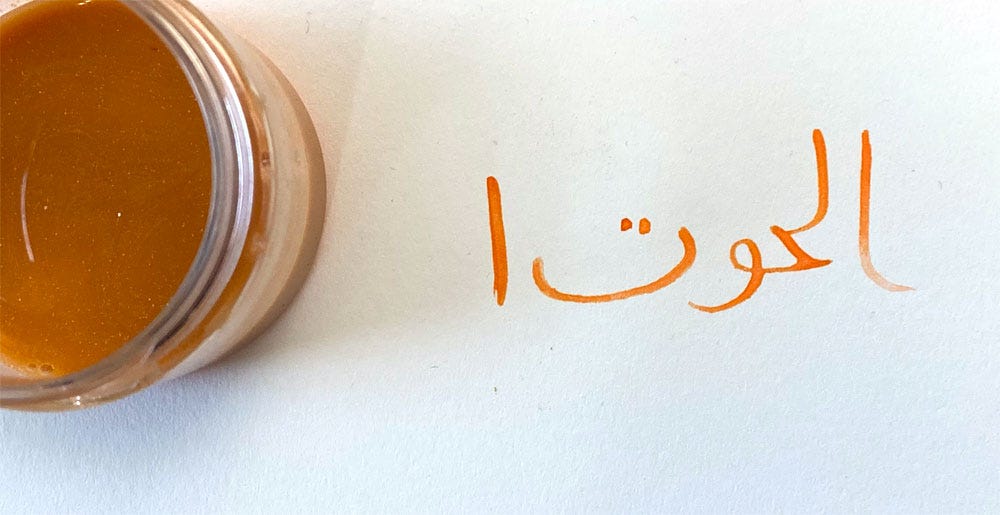

Pisces 1

الحوت الوجه الاول منه اشهب يصنع من زرقون مكسّر ببياض ويسير صمغ

“The first face of Pisces is (ashhab), made of minium tempered with ceruse and a little gum.”

To finish for today, this final recipe that offered another little puzzle. The colour of the ink in the text seems to be ashhab, which mostly means grizzled or grey, a coat with more white hairs than black. But the ingredients are unambiguous: minium or red lead is a bright red-orange, a substitute for cinnabar, and if it’s “broken” with white the result is still going to be orange no matter what. So there’s something wrong with the title here.

In these cases I have to remember I’m working from a transcript, not from the original manuscript, and there are so many moments in the original text’s transmission where a scribal error could have occurred and changed the word. It’s also possible that the meaning of this word simply changed over time. Digging deep in the dictionaries, I find that the word shihāb means “a piece of wood in which fire is gleaming or radiating” and one of its plurals is ashhub. Given the inevitable colour of this ink, it makes more sense to read “the first face of Pisces is like blazing brands” than the adjective “grizzled”. And here’s the result on paper:

Thanks for reading and I hope you’re enjoying this investigation. To be continued soon, and meanwhile I wish you all a happy new year!

The tree resin dragon's blood barely dissolves in water but it does dissolve in alcohol, clove oil and (I think) vinegar. Unless bought from an artists pigment supplier dragon's blood is probably a different preparation made from rattan tree fruit. This is sold for incense, herbal medicines etc and behaves differently. It isn't soluble in water either but does dissolve in alcohol. For ink it needs a binder of alcohol-soluble gum (frankincense, pine resin, mastic)(gum arabic, gum tragacanth and cherry sap don't work as they are only water-soluble)

Wonderful. I was first told about dragon's blood as a pigment by Daniel Chatto at the RDS in 2016. A Traditional Chinese Medicine herbalist gave me some solid crystals of it as it is used in herbal preparations. I ground it up for pigment, but it gave a disappointingly pale and transparent red, the colour of dried blood, when added to gum and water. I think both the quality of your resin and the method of preparation were better than my (then rookie) attempts.