In the first three volumes of this series I explained the thinking and chemistry behind gallnut-based, red and yellow inks for use during given decans. Today is more miscellaneous as I finish with a few more interesting recipes and the event behind it all.

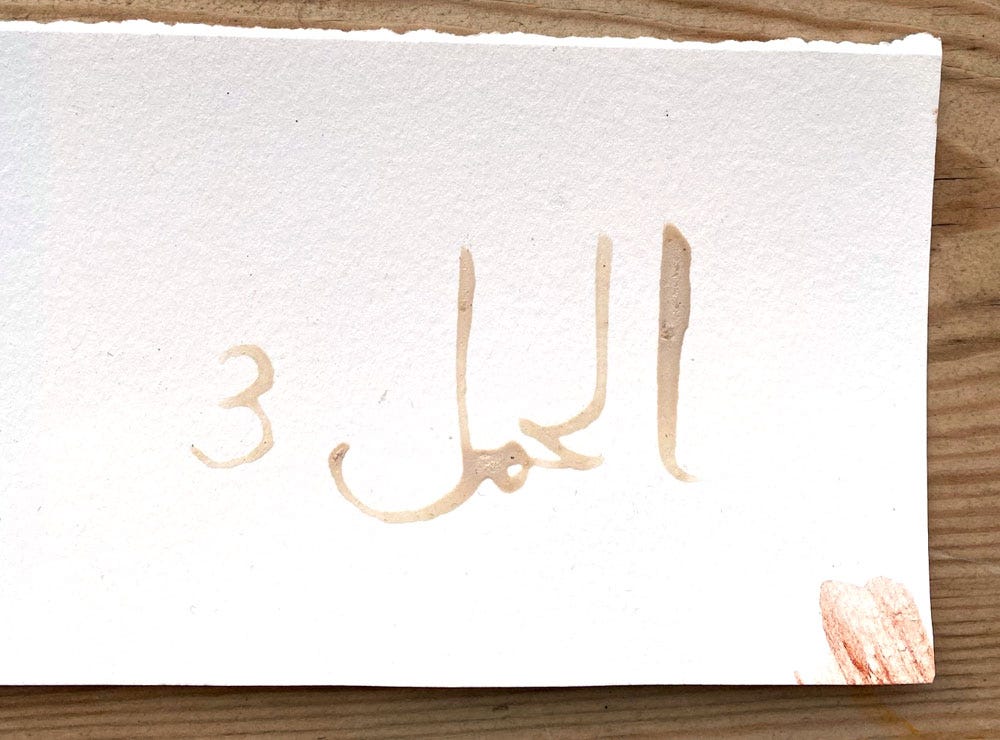

Aries 3

والوجه الثالث مداده أبيض يصنع من الطلق والبياض

“The ink for the third face is white, made with talc/mica and ceruse.”

Unusually, the recipe doesn’t specify gum. I added some to my preparation because without a binder, the lead white powder would remain loose on the paper, which is a serious health hazard. And this is why my result isn’t the pure white it would otherwise be: the slight beige tint is all due to the gum.

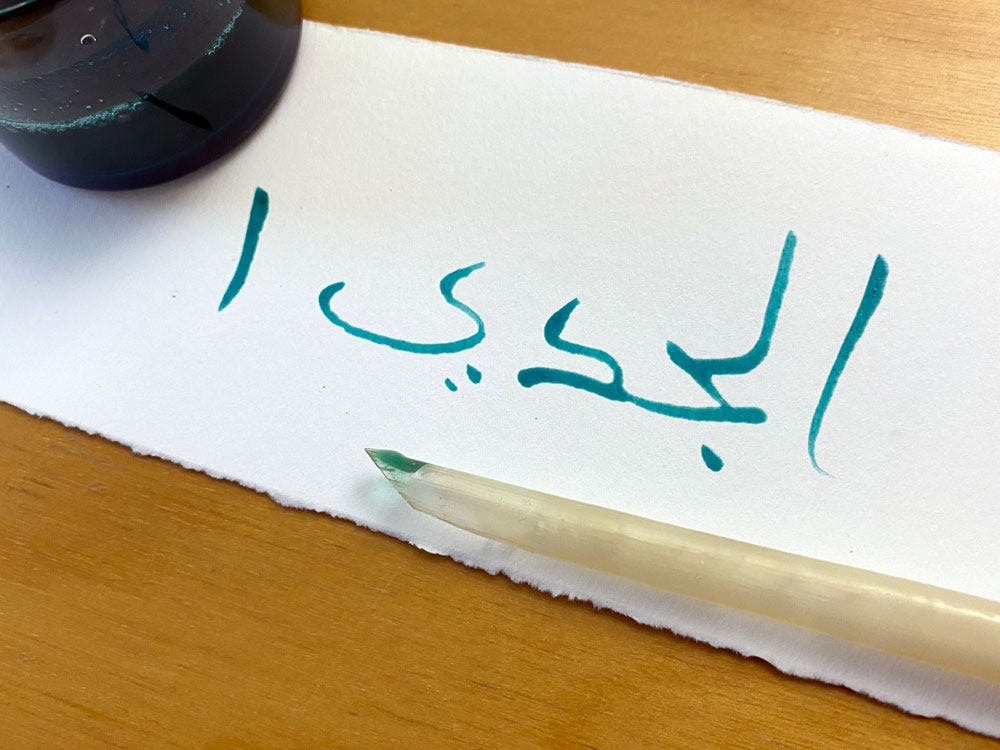

Capricorn 1

الجدي الوجه الاول منه اخضر يصنع من الزنجار ويسير صمغ

“The first face of Capricorn is green, made with verdigris and a little gum.”

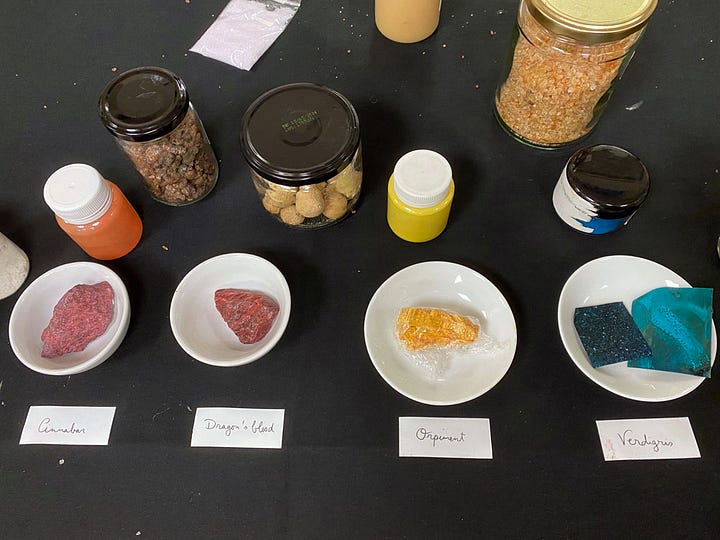

This rare green ink is very straightforward and right out of a scribe’s palette. At that point in time, verdigris was the only available green (save animal bile1). It forms naturally on copper and brass objects, and is extremely easy to make.

The colour is stunning, but it’s a temperamental substance that behaves somewhere between solid pigment and liquid ink. Above all, it’s highly corrosive to the support. I recently looked at the most beautiful early Qur’an that had holes punched out of the pages where verdigris was used for the vocalisation. This didn’t stop it being used, and the heavenly hue makes it obvious why…

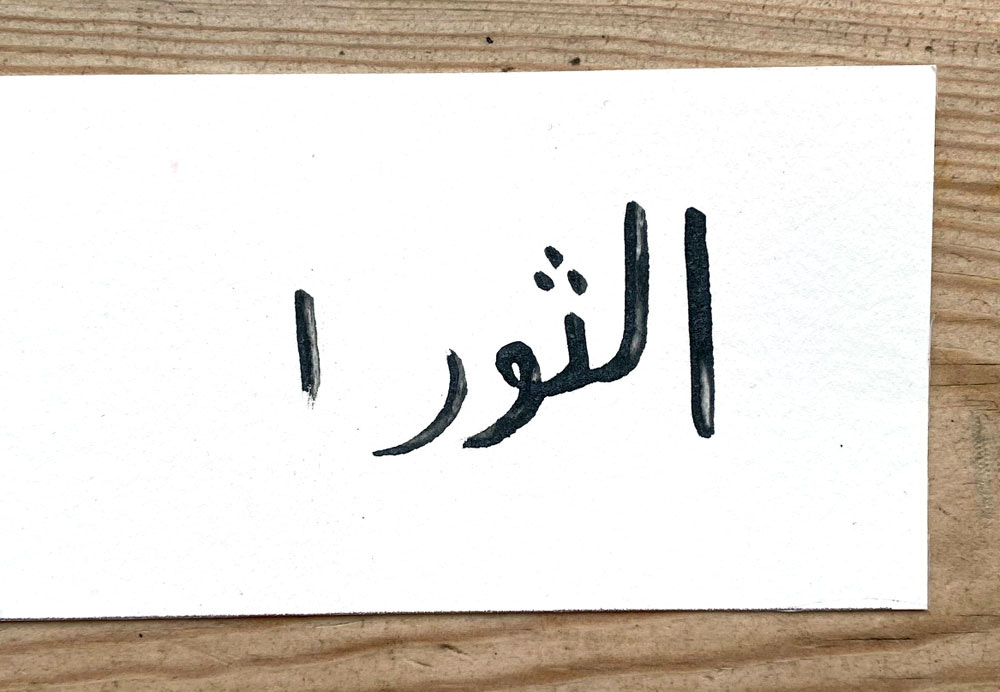

Taurus 1

الثور اول وجه منه مداده اغبر دخاني دفلي وعمله ان يؤخذ الدخان مجموعا في اعلى اثال ويوضع معه صمغ وغرا سمك درهم للاوقية ويسير باروق ويرسم به

“The ink for the first face of Taurus is viscous, soot-based and dust-coloured. It’s made by gathering the soot that has accumulated in the highest aludel2 and adding to it gum and fish glue in the proportion of a dirham per uqiyya [1/12] and a little ceruse, then it’s drawn with.”

The word used to describe this ink is "pitch-like". Pitch is so viscous3 it appears solid, but we're not looking for quite this extremity, as it's meant to be usable out of the jar. The recipe is straightforward: soot and gum make up a basic carbon ink, and the fish glue seems to be there to increase the viscosity. The ceruse is what makes it "dust-coloured", i.e grey, and there's normally no reason to add it.

The photo just gives an idea of how difficult it is to use such a thick ink, and it also makes it look darker – in reality it’s quite dull, exactly as the recipe says.

Aquarius 2

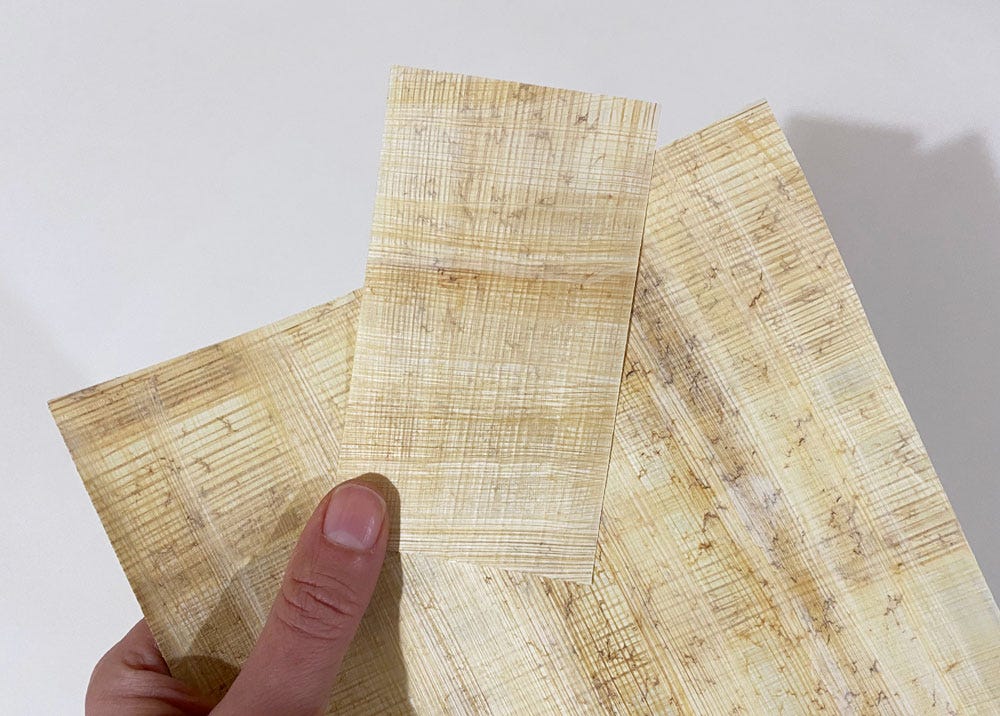

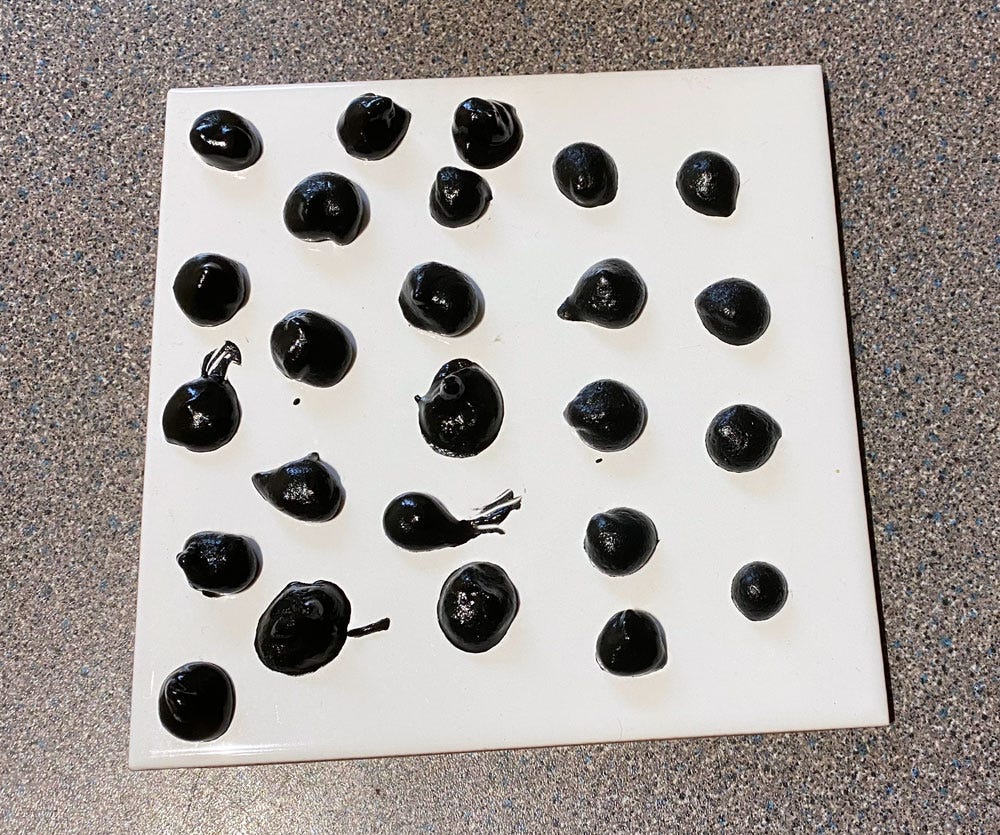

والوجه الثاني اسود وعمله ان يؤخذ مداد فارسي جيّد وصمغ وعفص من كل واحد جزء وقراطيس محرقة نصف جزء ويدقّ ذلك كله وينخل ويعجن ببياض بيض ويتخذ بنادق ويجفّف وعند الحاجة يحلّ ويرسم به

“The second face is black, and is made by taking good Persian charcoal, gum, and gallnut, one part of each, and half a part burned papyrus [or paper scraps]. Pound all together and sift. Knead in egg white and roll into hazelnut-sized balls. Let dry, and when needed dissolve and draw with it.”

This one is very familiar: it’s taken word-for-word from al-Razi’s treatise Zīnat al-Kataba (§3 in my translation). The word qarātīs referred to papyrus before it started to be used for paper (known then as kāghid), and in the context of the Zina (and the Ghāya) I’m fairly sure that it still means papyrus. Even after it stopped being used as a writing support, papyrus was still around for other purposes such as wrapping things. I don’t think we should understand the recipe as calling for good papyrus to be burned, but scraps – in the same way that old linen rags no longer suitable for other uses were also burned to make black ink.

As it turns out, I have a few sheets of papyrus in the studio…

In the absence of a hearth, I burned as much as I dared inside my stainless steel pot, a small piece at a time.

As you can see, once pounded down and brushed into a pile, it’s not a large amount.

It would have been futile to weigh, so I eyeballed the other ingredients. The gallnut plays absolutely no part in this ink because there is no vitriol to form a black precipitate. It’s probably there because the presence of tannin was always desirable in an ink. The reason is not explicit but I feel it has to do with its mordant quality: if it can tan skins so that they become durable leather, it must make writing equally long-lived (so I am guessing the thinking went).

I added a little too much egg white so I had to leave them to dry a bit before I could roll them properly. The result is a good black ink suitable for a scribe.

Pisces 2

والوجه الثاني اغبر يصنع من الطرفة شوكة محرقة ويسير صمغ وارسم به

“The second face is dusty, made with burned thorn [acacia tree] and a little gum; draw with it.”

Another type of carbon ink, this time made directly with burned material. After identifying the tree mentioned as Acacia arabica, I did what I always do – ask eBay. To my surprise, there it was:

Next came the question of how to burn it. Eventually I figured that if I could burn a slice of bread under the broiler, I could burnt wood chips too… The oven also felt like a safe place for anything to combust, so I spread the bark in this trusty saniyye and set it under the broiler.

It worked a treat!

Once perfectly cooled, I pounded this to a fine powder, but the net result of burning something directly is you’ll always have lumps and incompletely burned bits that won’t powder. So sieving was going to be needed, which I did through a coarse-mesh cloth, as specified in other inkmaking manuals.

The result was nice and fine, and also, as you can see, not terribly dark. In my book Inks & Paints of the Middle East I discuss the three types of carbon ink: soot, char and ash. This is ash, the simplest to make, but the poorest in terms of blackness. Soot is blackest, char is the way to get deep black from burned substances, and ash will inevitably give you the dull or dust colour described in the recipe. As it was so specific about the tree used, though, the colour is probably not as important as the symbolism or medical/magical properties of acacia itself (which is also the source of the all-important gum).

The finale

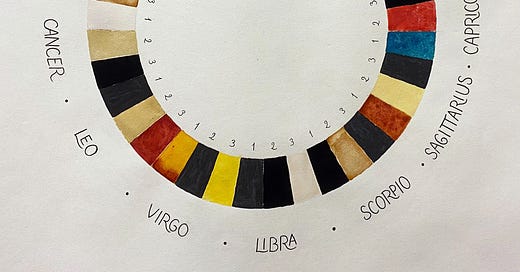

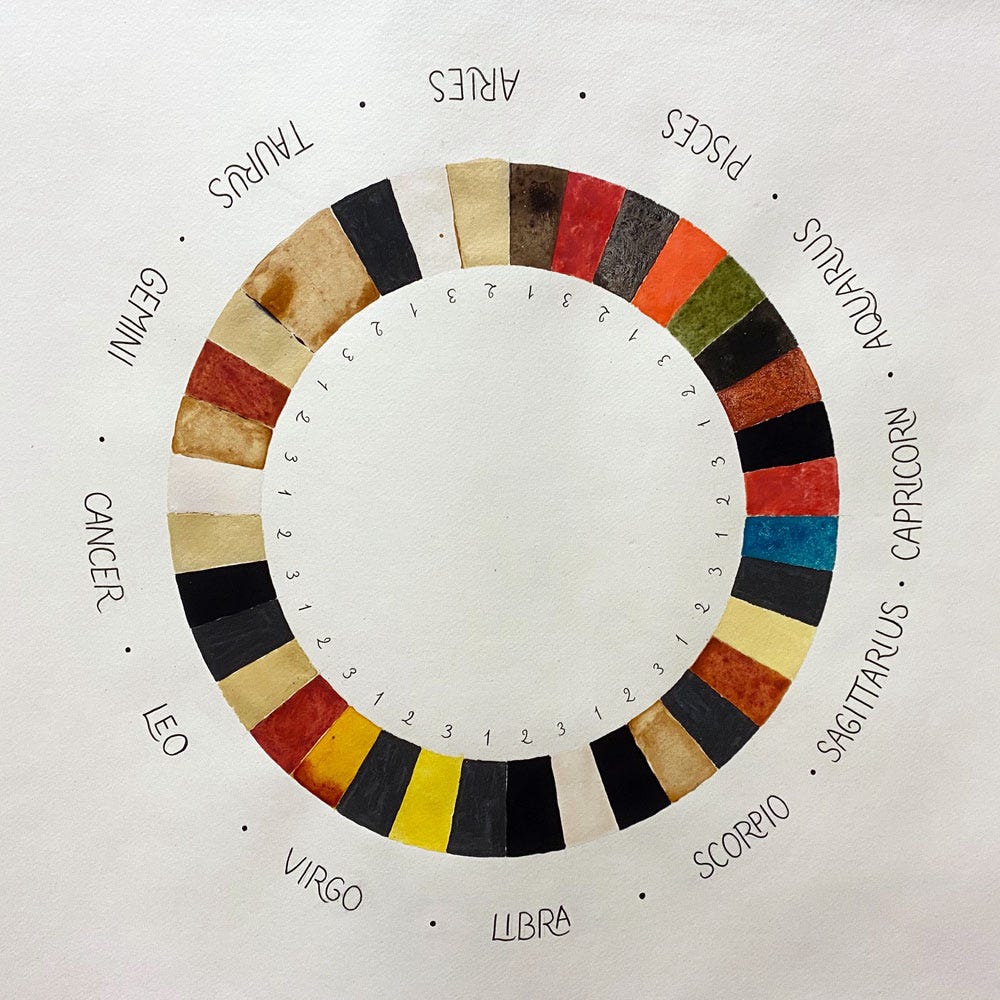

And here’s how they all look, put together: the colour chart of the decans according to Ghāyat al-Hakīm.

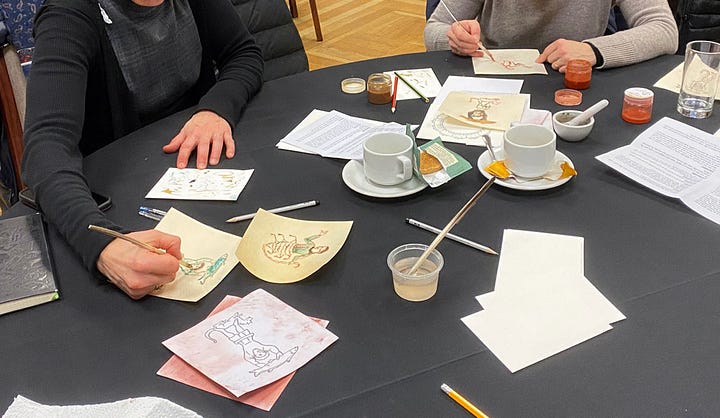

This project was concluded on Friday January 13 (yup) at the Warburg Institute’s conference “Science and Craft: the relations between the theoretical and practical sides of the occult and esoteric sciences in the Islamic world”. Where a group of brilliant scholars sat down to get their hands dirty and make some talismans…

Aquarius 3 is a green ink made of animal bile, but I didn’t attempt it. A few centuries later, lamprey bile was used for this same purpose in Western manuscripts.

A subliming pot used in alchemical work. Here the implication is only the finest purest soot would collect there.

To the point that in this experiment begun in 1927, the ninth drop fell in 2013 after 69 years. The tenth drop is awaited sometime during the 2020’s.

Hey Joumana, my name is Izzy. I am a student of the Picatrix, and am in the midst of a deep, creative project that revolves around the garnments one should wear while petitioning the planets, according to the Ghāyat al-Hakīm. I am so grateful for your work here! The decanic inks were a part of the book I was looking forward to experimenting with, but, my lack of specific knowledge led me down week long rabbit holes wayward drifts. I promised myself one more research dip, and lo and behold found part 1 of your project (published on my birthday, no less!). So amazing to see the colors and the process... thank you so so much. I wonder if I could introduce your work to my teacher and our class? I know everyone would be equally as thrilled :) - an extremely grateful izzy

Curious that the Arabic tradition doesn't seem to include malachite, which makes a beautiful emerald green and was used by the ancient Egyptians and in the 12 century Winchester Bible