Creative Dens

Albrecht Dürer's 15th c. studio

(I’m still away as you read this; this is another scheduled post!.)

As an artist, I love seeing others’ studios and I know how much visitors enjoy looking around my own. Some parts of it are definitely set up for visual delight rather than functionality (my own as much as any visitor’s!) and I was terribly amused to find out artists have been thinking along the same lines for centuries.

As a lean towards pre-industrial art practices, I’m particularly interested in older workshops, and make sure to catch any opportunity to visit one.

Last year I found myself in Nürnberg for all of one morning—an absolutely lovely town worth the trip, and home to Albrecht Dürer. I’m not a big Dürer connaisseur but I do love the aesthetic of his woodcuts, and am also aware of his particular genius and position: trained as a medieval craftsman, he made for himself that transition to individual artist that defined the 15th century. And his house somehow survived the WW2 annihilation of the medieval city, and is now a museum. How could I resist?

Let’s appreciate the (reconstructed) 15th-century interior to begin with…

Up top is the part that interests me the most: the studio! And yes I have massive studio envy there.

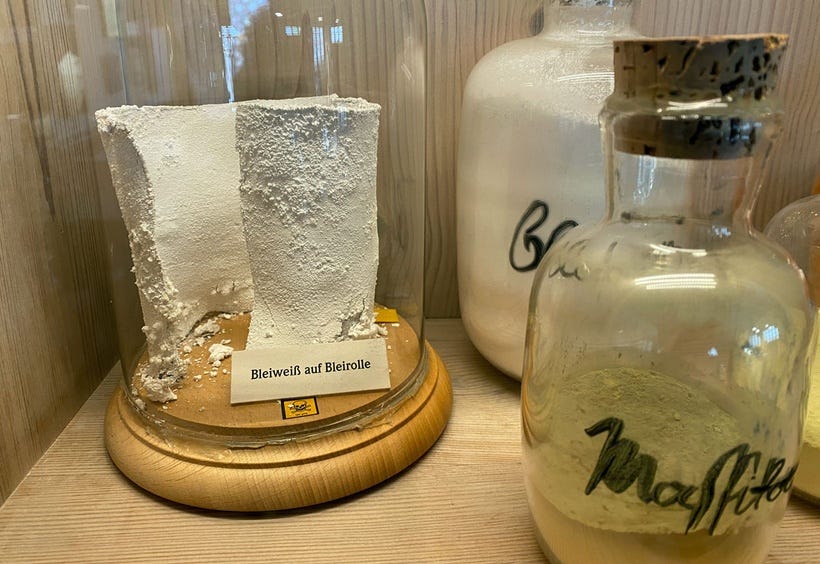

The display of period materials that would have been used by the artist is always of interest to me, and this one was unusually thorough! I’ll take you through the various display cases:

Then there's a long display for ALL the plant (and other organic) dyes. To use them in painting, they’d have to be precipitated into solid lakes1, but they could have been used simply in ink form, for instance to colourise prints.

Finally, this small cabinet is dedicated to gums and resins...

Upper shelf: Gum arabic; mastic; skin glue; fish glue.

Bottom shelf: Gum ammoniac (for gilding), colophony2, and finally myrrh and frankincense3. Note the unlabeled eggs in the back too, to make tempera paint. There's no indication of oil in the display but Dürer did use it as a medium.

He is however, known above all for his engravings, and no tour would be complete without the press room...

There are samples of woodcut plates and moveable type in the display case:

As for what’s set on the press itself, it’s the cherry on the cake!

The original plate was a woodcut, and this is a metal reproduction, but it was still very very exciting to meet the famous Rhinocerus in this setting. Despite not being an accurate representation, it’s been said that “probably no animal picture has exerted such a profound influence on the arts”4.

Ending the visit on this beauty, hope you enjoyed the tour!

This is a much simpler process than it sounds, though not all plant colours can withstand it. I describe how to do it and many more plant colours in my handbook Wild Inks & Paints.

Also known as rosin, it’s used to make varnishes, but more for musical instruments than paintings as far as I know. But it’s also an ingredient of the paste that allows the extraction of lapis lazuli.

In the Islamic world they were used to scent and/or preserve ink; I don't know what used they were intended to have in this Western context.

Clarke, T. H. The Rhinoceros from Dürer to Stubbs: 1515–1799. London: Sotheby's Publications, 1986.

How incredible! Thank you for the detailed close ups - I can see things I’ve only read about - the murex snail! Swoon! (They look bigger in real life, everyone writes about how tiny they are). I wonder if that the real murex or just an example the way the cochineal is. I digress. I trolled through your photos with utter glee, thank you.

I can relate. Reminds me of how I, a writer and bibliophile, feel about my personal library.