Everyone, I believe, has heard of lapis lazuli, the blue so precious it has acquired a quasi-mystical aura – at least in the medieval West. It was not so in the East at the same period, as I’ll be discussing below. The pigment known as ultramarine is a truly mesmeric hue, but the origin of its mystique is pragmatic: because it was so expensive, European painters reserved it for the holiest figures, such as the Virgin Mary, and thus it became associated with a celestial quality1.

So why was it so expensive in the first place?

To begin with, all of the lapis lazuli used in pre-industrial times came from the province of Badakshan in Afghanistan2. Its use as a pigment in that region is known from at least the fifth century BC, but it’s not until the late Middle Ages that it reached Western Europe. It was and still is relatively scarce.

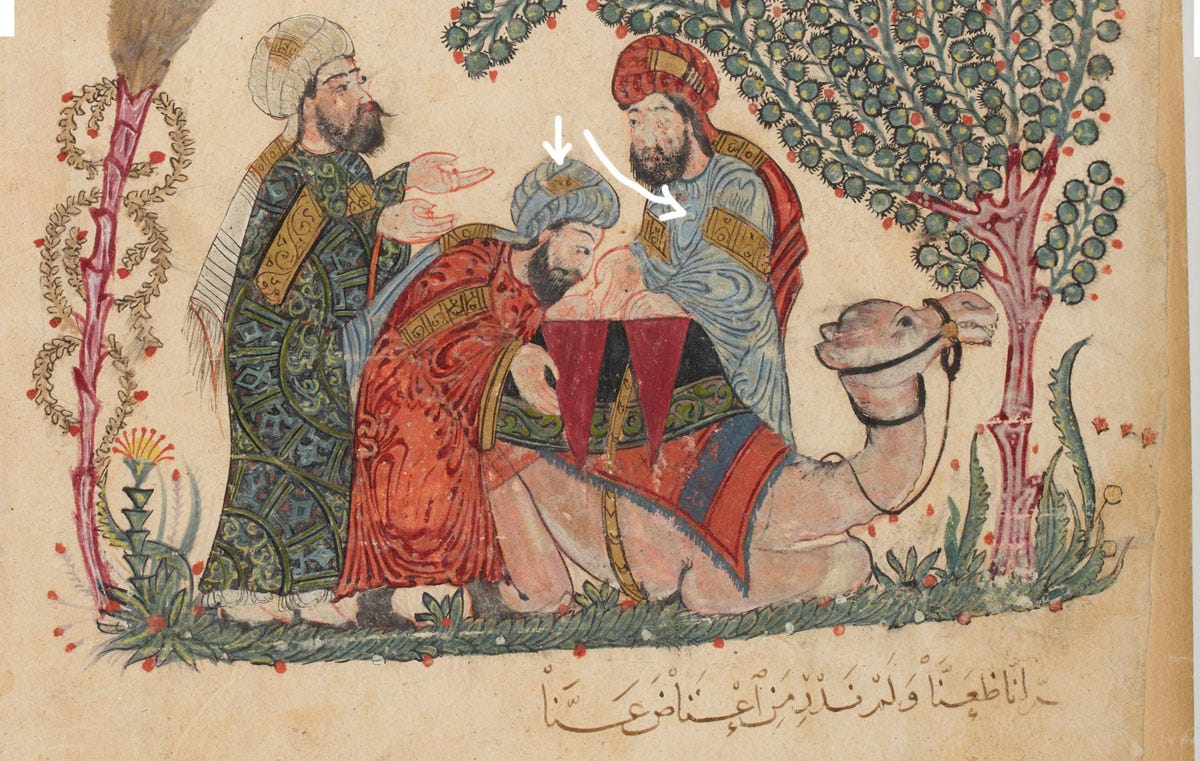

Then, there is the difficulty of extracting the pigment itself. Lapis lazuli is a compound of various minerals, notably calcite and pyrite, alongside the blue component which is a pigment called lazurite, and some silicates. Usually colour pigments are separated from their matrix through a process called levigation that basically means you reduce it to powder and use water to separate particles that have different densities. It’s an incredibly simple process that is remarkably effective for simpler minerals, but scuppered by the complexity of lapis lazuli (which also happens to be a really hard stone). For the longest time, colourmen dealt with this by simply sourcing very high grade lapis and grinding it down finely – taking out major impurities with tweezers when possible3. It’s only in the twelfth century that a method was devised to separate pure lazurite from the other components, and thus make ultramarine. This is where East and West diverge. Although it was Arab alchemists who worked out this technique, they seem to have had no interest in this refined pigment. It’s obvious why when you look at the way they used it: as a flat colour to make blue marks in the text or in marginal decorations, or for mixing with white, verdigris or cinnabar to achieve other colours.

Such a use requires a pigment with good opacity, which ground lapis has thanks to the calcite content, even though this very calcite makes the blue slightly clouded. Lazurite/ultramarine is not at all opaque, and a novice applying it directly on a white surface would be disappointed. The secret of its blue glow is in using it as a glazing colour, either by using many layers to achieve the deepest blue, or by finishing off layers of a cheaper blue, or by using its transparency to good effect, as shown in the Vermeer example below. Such techniques developed in the figures-focused Christian art tradition, paving the way for European realism.

Knowing this, it’s worth pointing out that 500g of ground lapis, ready to use, yield only about 20g lazurite: you can see why this would be a total waste for an Islamic artist, while for a European this desirable refining would seriously raise the cost of the material.

It was in Europe therefore that lazurite extraction continued to be improved, and the best-known method today is probably the one Cennino Cennini put down in his famous fourteenth-century handbook Il libro dell’arte. Here’s how it goes, step by step4.

1. Grinding

To grind a specially hard stone into fine powder without mechanical aid, you take a leaf out of Hannibal’s book and start by weakening it with heat and vinegar. When the cold liquid hits the heated stone, any weaknesses in the crystal become minute cracks, exacerbated by the acid dissolving some of the calcite.

It can then be pounded vigorously so it breaks down, and when it breaks no further, the above steps are repeated, as many times as necessary until all of it is fine enough to go through a sieve.

2. Washing

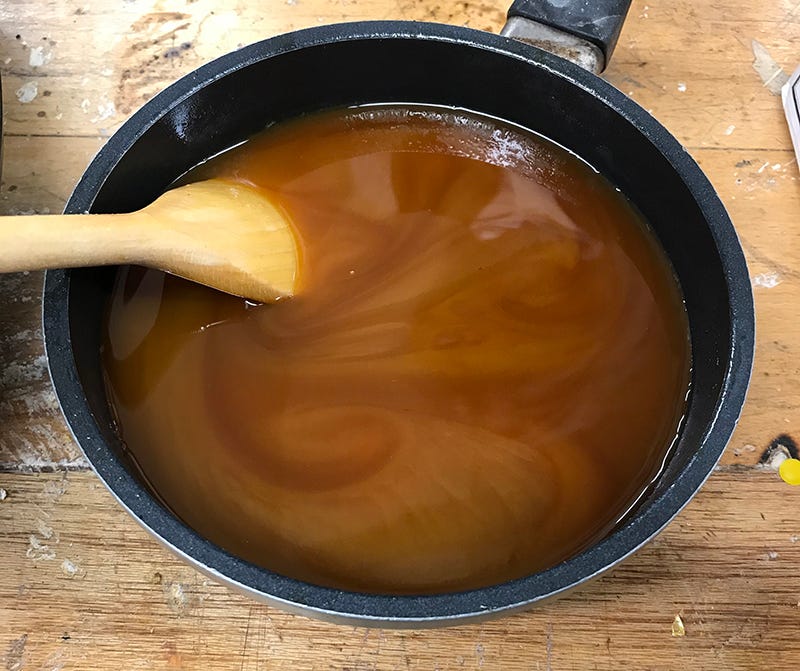

At this point the pigment is levigated, as it inevitably contains some dirt that needs washing out. You can see it rise to the surface, as in the jug on the right below, as soon as you add water. The heavy lapis sinks to the bottom and the dirty water can be carefully poured out, repeating the process until no dirt remains.

This is where the old method ends. It’s also where the process stops for most of the lapis lazuli pigment you may find on the market, probably because that’s as far as mechanical processing can take it. You can tell from the price: if it feels "not that expensive", this is what you're getting; after all, as a stone, lapis lazuli is only considered semi-precious, and isn’t very pricey. But ultramarine costs around the same as gold, even today.

To separate the components further we have to work by hand, and it begins by preparing The Putty.

3. The putty

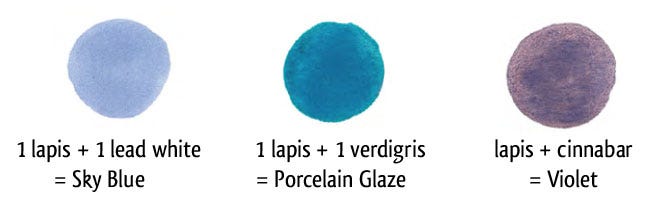

This preparation is made up of several ingredients such as beeswax, colophony, mastic, linseed oil and silver fir balsam, basically a number of natural sticky substances.

This stuff looks and smells like a dessert of caramel and toffee with nuts as everything is melted down together. It’s quite hard not to absent-mindedly dip a finger in to taste it.

4. Union

The slightly cooled putty, now unbelievably sticky, is now kneaded with our lapis powder until it’s so saturated with blue that it feels and looks like polymer clay.

It’s now rolled into little logs that are set aside to rest a couple of days. Which is about the amount of time it takes you to get all that resin off your hands.

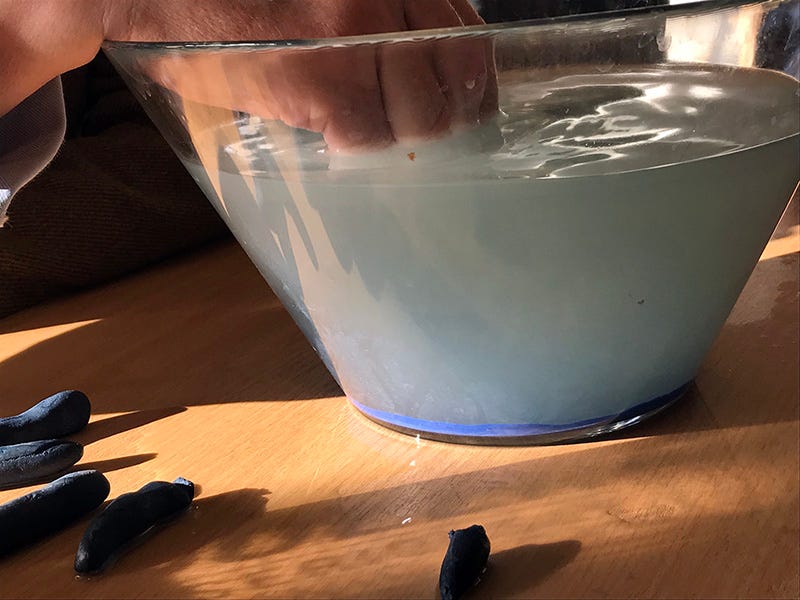

5. Separation

This step alone can take several days. Slowly, gently, one hazelnut-sized bit at a time, the putty is massaged in alkaline water. This is the crux of the operation: by this very slow and patient process, the lazurite is pulled out of the putty while the other components are retained by it.5

For a long time it seems like absolutely nothing is happening, until you start noticing a buildup of blue.

This method cannot be reproduced industrially because human hands are absolutely necessary: the hands regulate both the water temperature and that of the putty, which needs a bit of warmth but falls apart if too warm; and fingers need to feel and respond to the texture in order to always keep the pressure just right. If you rush or press too hard, the putty can melt onto your fingers in the water, it can get frittered away and become a nightmare to remove from the pigment later... But gradually all the blue in your hazelnut has fallen into the water and the remaining putty looks all grey, as below. So you move on to the next, until you run out of blue logs.

6. Final wash

One final round of levigation to get any putty crumbs (like this smidgen on the right) out of this glorious blue…

Finally, it's ready. And if you’ve gone through the whole process, you’re unlikely to waste a single grain of it…

In a similar way, the purple dye produced by the Phoenicians in Antiquity was so dear only the richest of the rich, such as Roman emperors, could afford full garments dyed with it; high-ranking officials had to be content with a purple edging or similar. The colour became a de facto symbol of imperial power and was later so inseparable from Byzantium that it seems to have been entirely avoided by Islamic rulers. The status of Tyrian purple far outlived the production of the dye: in 2022 the Platinum Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II had an ostentatiously purple colour scheme. Don’t believe any article that claims someone has rediscovered the secret of purple dye, by the way: it was never lost, it’s just completely unsustainable.

It’s only recently that the pigment started to be sourced from Siberia and Chile, but the hue is noticeably different.

Sometimes known as Fra Angelico’s method.

Photos from a workshop I took with David Cranswick at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts.

Medieval science had a really interesting way of explaining this phenomenon, detailed by Spike Bucklow in his fascinating book The Alchemy of Paint: Art, Science and Secrets from the Middle Ages: Colour and Meaning Fom the Middle Ages. I recommend it for greater detail, but put briefly, this was based on the doctrine of the four elements, and the notion that everything in the world wants to return to its own element. Elementally, the lazurite in lapis lazuli belongs to Water. The pyrite, which sparkles and mirrors the stars, belongs to Fire, while the calcite is made up mostly of the Earth element. The putty we prepared is made up entirely of Fire-related ingredients: tree resins with solar association, golden beeswax and oils. The pyrite therefore is where it wants to be and will never leave the putty. The lazurite on the other hand wants nothing better than to escape the fiery putty and join the water where it belongs. As for calcite, it has affinities to both Fire and Water (because Earth is dry like the former and cool like the latter) so it doesn't really mind; it does tend more towards rejoining water, but being a static element it can only move very slowly. And in fact the calcite does eventually emerge, which is why the first batches of lapis are the deepest colour, but after a few changes of water you get "ultramarine ash", tainted with calcite. I’m neither holding it up as the truth not putting it down as superstition: I find it a striking empirical way of describing a practical phenomenon. I don’t know whether this theory inspired the putty method or came to explain it after the fact.

A fabulous article! The blue of lapis lazuli is one of my favorite colors in art. The way different civilizational spheres place a differing, sometimes opposing value upon different substances is always fascinating as well. An extreme example of that is the Spanish deeply cherishing gold vs. the Aztecs and Incas being less obsessed apart from valuing its decorative qualities. I guess lapis lazuli is another example of that, but without the financial dimensions of gold.

Great article. It boggles my mind how this process was thought of in the first place. I wonder what the mineral composition differences are between the Afghanistan and the other lapis sources (I think you said Siberia and Chile?) are to make a color difference in the final product.