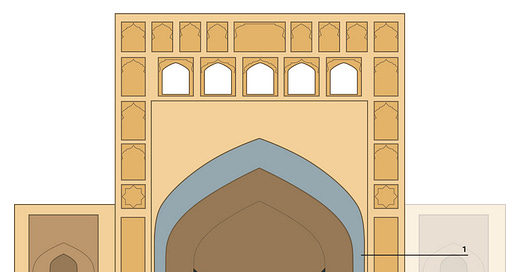

I’ve returned from my travels to jump straight back into the world of Square Kufi, which I’m teaching at the same time as I continue the survey for my book. For today’s post I’m returning to the heartland, so to speak: to the best of our knowledge, this style first took shape in Ghazni, modern-day Afghanistan, in the very early 12th century, though it only really took off more than a century later. Yet there are hardly any examples of the script to be found in the country now, largely due to the fact it has endured so much, very little has survived into modern times – and what is there is not easily accessible and photographed. Other than a shrine in Balkh, the nearest monument in my files is near Herat: the shrine of Khwaja Abdallah Ansari in Gazurgah, built by the Timurid ruler Shah Rukh in 1425.

Ansari of Herat was a Sufi scholar and teacher of the 11th century (d.1088), who came to be seen as the patron saint of the city. His shrine was built as a funerary complex, where citizens of high status could be laid to rest close to their patron.

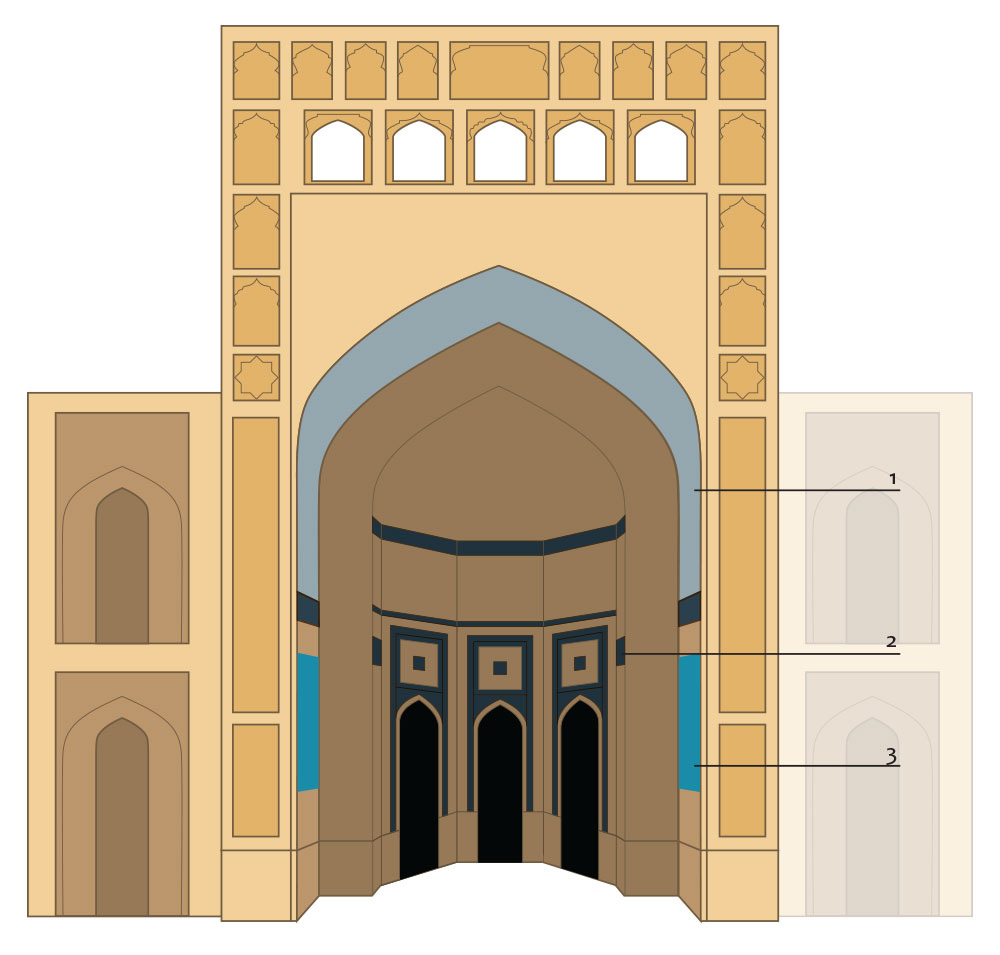

While most of the walls and iwans are filled with the large-scale patterns of brickwork script, the East iwan concentrates a number of small but very rich designs in Square Kufi. There may have been much more, but the site is very dilapidated with much of the tilework gone, erasing any further texts forever.

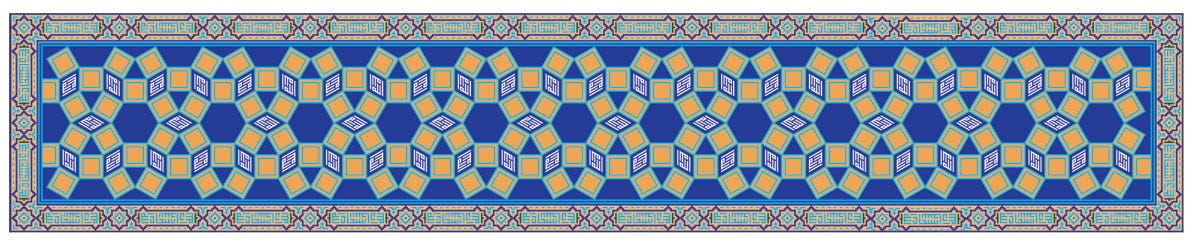

1 is an ornamental band that covers the inside of the arch. Below is the full band when unfolded, but I present it very simplified, without its many geometric and floral details.

Of course the reason I’m mentioning it at all is because it contains some text:

Two small pieces of text, to be accurate. The word Allah, in pairs skewed into a diamond throughout the pattern, and سبحان الله (‘Glory be to God’), also paired, in the border around the band.

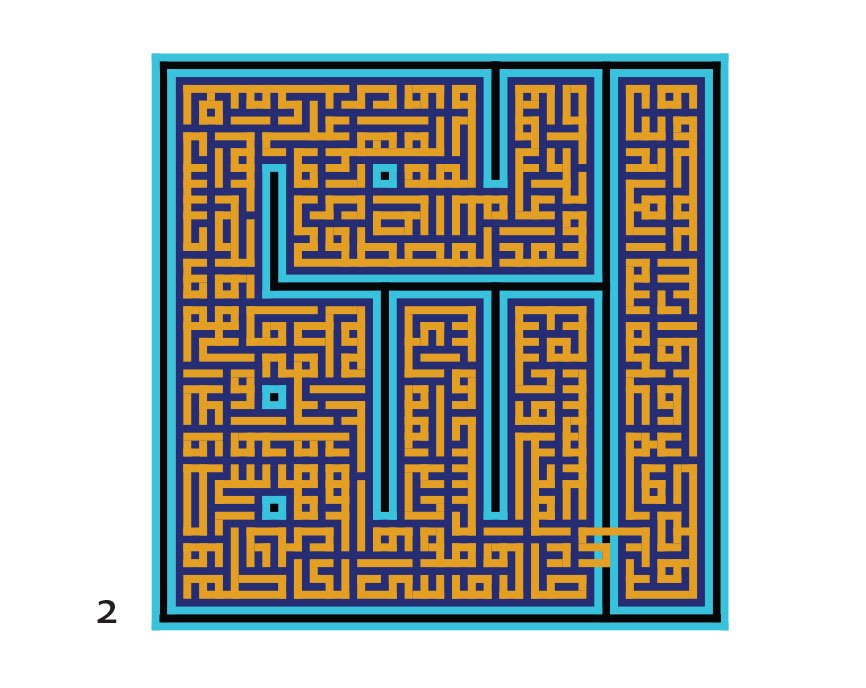

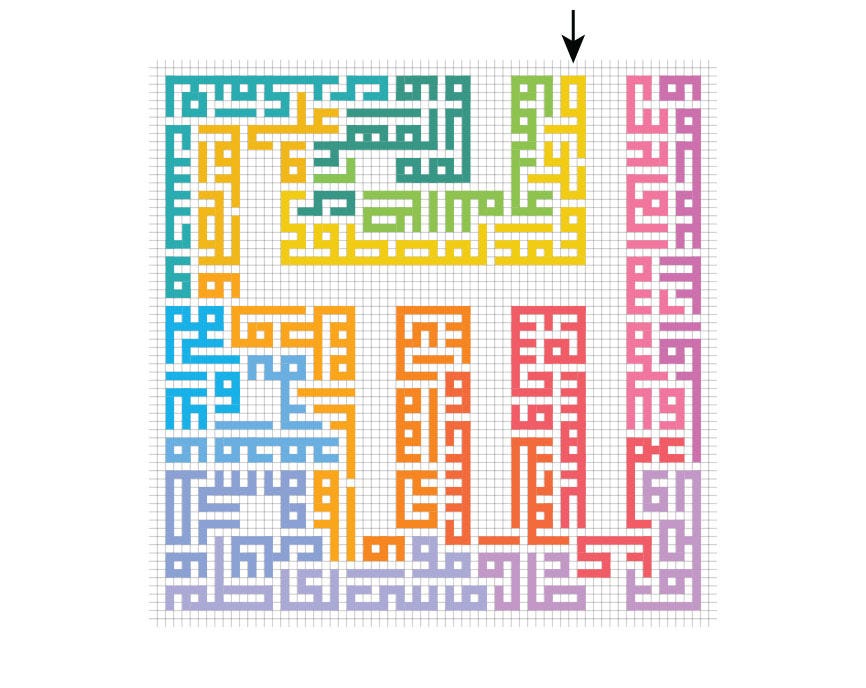

On either side of the three doorways, we have two instances of one of the most exciting types of Square Kufi—text arranged in the shape of a word:

The container word is اللهمّ (‘O God’) and the text is a prayer for the Fourteen Infallibles, deconstructed below.

Starting where the arrow points, and wrapping all the way around the word and back, it reads (with a number of “typos” I won’t detail here):

صل على محمد المصطفى وعلي المرتضى وفاطمه الزهراء وخديجه الكبرا وحسن المجتبى وحسين شهيد كربلا وعلي زين العابدين ومحمد الباقر وجعفر صادق وموسى الكاظم وعلي موسى رضا ومحمد التقي وعلي النقي وحسن العسكري ومحمد المهدي رضي الله عنهم

‘Pray for Muhammad the Chosen, and Ali the Beloved, and Fatima the Luminous, and Khadija the Great, and Hassan the Chosen, and Hussein the Martyr of Karbala, and Ali Ornament of Worshippers, and Muhammad the Opener, and Jaafar the Honest, and Musa the Confined, and Ali [son of] Musa the Pleasing, and Muhammad the God-fearing, and Ali the Pure, and Hassan the Soldier, and Muhammad the Mahdi; God is pleased with them.’

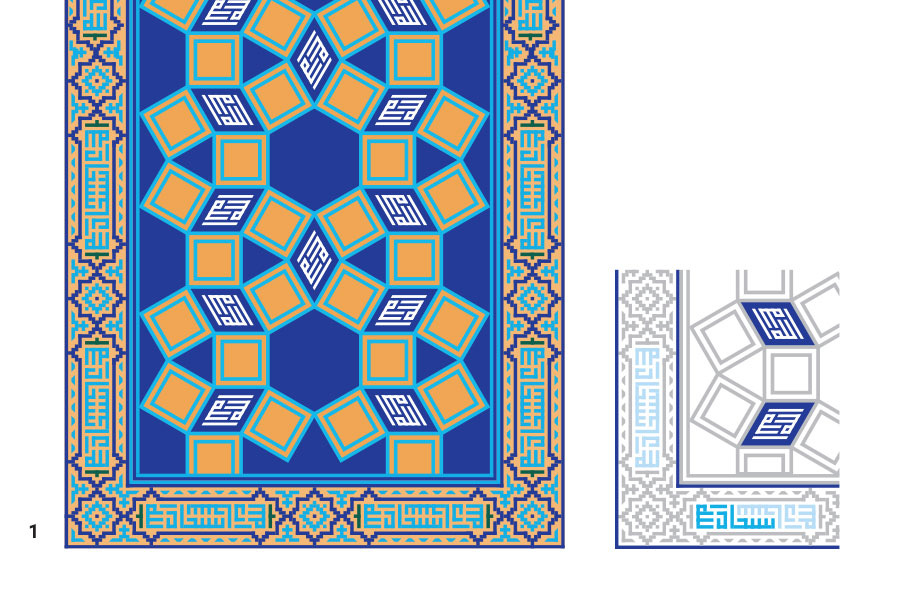

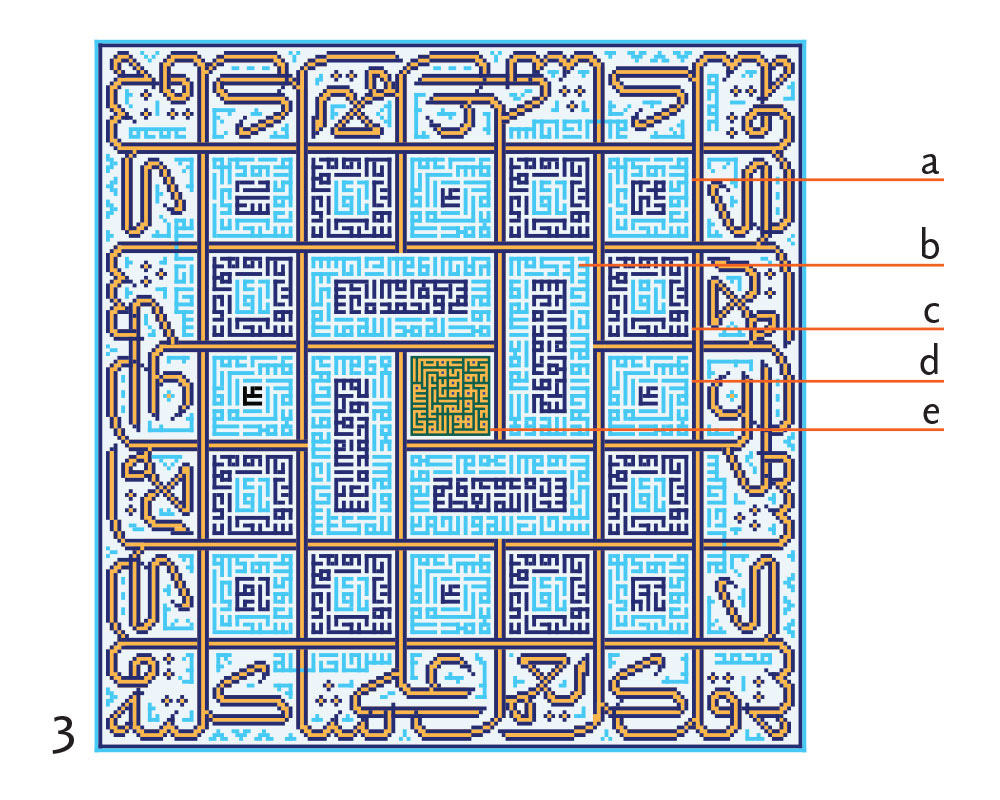

The jewel of the shrine, however, is probably the following panel, also facing its twin across the archway:

We probably owe this design to the shrine’s own architect, Qavam al-Din of Shiraz. It’s a clever and beautifully envisioned play on rotational symmetry and the textures of different scripts: 5 units of text forming a rectangle are rotated to create the large square, with a different text in the empty centre. Meanwhile the borders for the different areas are defined by tall letters from the cursive inscription in gold (Q 17:84 ‘Everyone acts in their own way’ – whether it was chosen for its contents or for the handy arrangement of tall letters, I couldn’t say).

Each of the smaller blocks is made up of a brief sentence around another, even briefer core:

a. The core text is actually different every time, but this one readsيا ستّار (‘O Veiler of Sins’). Around: سبحان ذي المُلك والملكوت (‘Praise the Lord of the Visible and Invisible’).

b. Inside: سبحان الله العظيم وبحمده (‘Glory to God the Almighty and praise Him’).

Around: سبحان الله والحمد لله ولا اله الا الله والله اكبر (‘Glory to God; praise to God; there is no god but God; God is greatest’).

c is used twice in each rectangular block so it appears 8 times in total. The core text is يا قادر (‘O All-Powerful’). Around: سبحان ذي العزة والجبروت (‘Praise the Lord of Glory and Might’).

d is the profession of faith, the most ubiquitous of texts: لا اله الا الله محمد رسول الله علي ولي الله (‘There is no deity but God, Muhammad is God’s messenger’).

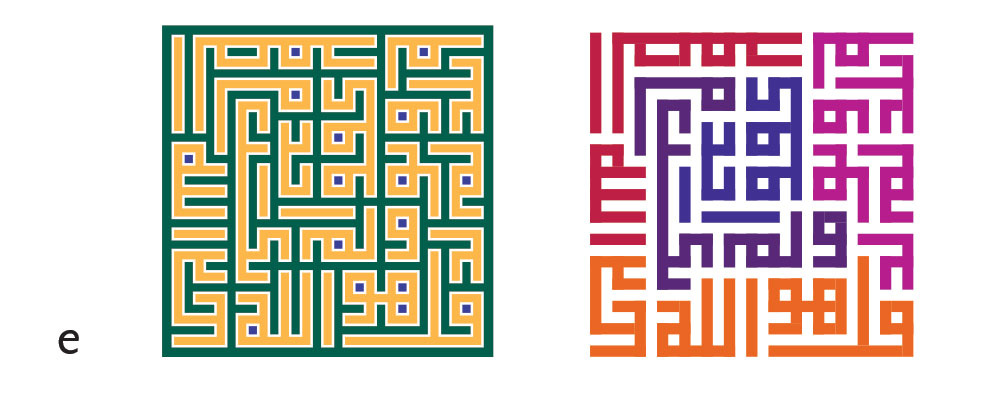

Finally, the square centre of this complex arrangement is filled with one last text. This may have been an afterthought, because there is no relationship of proportions (or colours) between the two and the eye does register a little awkwardness.

This text is Surat al-Ikhlas (Q112:1-4):

قل هو الله احد الله الصمد لم يلد ولم يولد ولم يكن له كفوا احد

‘Say: He is God, the One and Only;

God, the Eternal, Absolute;

He begetteth not, nor is He begotten;

And there is none like unto Him.’

I’ll finish with a little follow-up on my previous post in this series, where I discussed the deliberate introduction of imperfections in the work. Caroline Ross, author of

, contributed this insight:[T]he master knitters of Shetland, whose incredible woollen shawls must be fine enough to pass through a wedding ring, always add a deliberate mistake stitch into their otherwise perfectly symmetrical works. There is no way the mistake is accidental. These women are masters of skill. The practice comes from exactly the same belief as you mention, that only God creates infallibly, and all human works should contain humility and not seek absolute perfection.

She also referred me to Dr Theresa Emmerich Kamper, expert in ancestral crafts, who says “the same 'rule of imperfection' applies in certain craft traditions in Navajo and Hopi lineages”.

I have no doubt that we would find this practice in many other cultures. How might today’s world look if keeping hubris at bay was still normalised?

Thankyou for this excellent post.

Having just returned from a spending time with Dr Iain McGilchrist, author of 'The Master and his Emissary', I am beginning to wonder even more about these 'flaws' as part of an antidote to the what I call the Hubriscene (or as Mohamed Amer Meziane puts it, the 'Secularoscene.) Only machines create with infinite uniformity. To wish ourselves as machines, or to attempt to be like them, is surely half of how we got in the current predicament, globally. Yet to not strive for excellence in an art or science is a waste of our faculties and a disservice to others. I think this conundrum is in plain sight with your analysis of Kufi in architecture (which I am finding very generative): the 'typos', the choices of texts, the squared script within the buildings' soaring curves. There seems to me to be a wonderful conversation going on between the fluid expression of cursive ornamentation and the modular, linear, Kufi.

(Here is where I found Meziane's talk on the Secularoscene, in case it's of interest - https://dougald.substack.com/p/the-burden-of-being-heaven )